Challenge

People have been creating ceramics for thousands of years. But today’s ceramic materials are used for more than cooking. They undergo extreme high temperatures in situations like industrial processing and space flight.

There is little understanding of how materials deform at high temperatures due to mechanical stress because of the difficulty in duplicating the extreme conditions materials endure in some modern applications.

Tests have been performed on large samples, but it’s been almost impossible to see how damage occurs in nanoscale samples. This is especially true for zirconium dioxide (ZrO2), which melts at the extremely high temperature of 2715° C, too hot for conventional microscopes.

“Zirconia has been likened to ‘ceramic steel,’ and is critical to a wide range

of applications. With the unique facilities and experienced staff at Sandia, we were able to broaden our understanding of this incredible material in real time under extreme conditions.”

Jessica Anne Krogstad

Associate Professor

Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

Collaboration

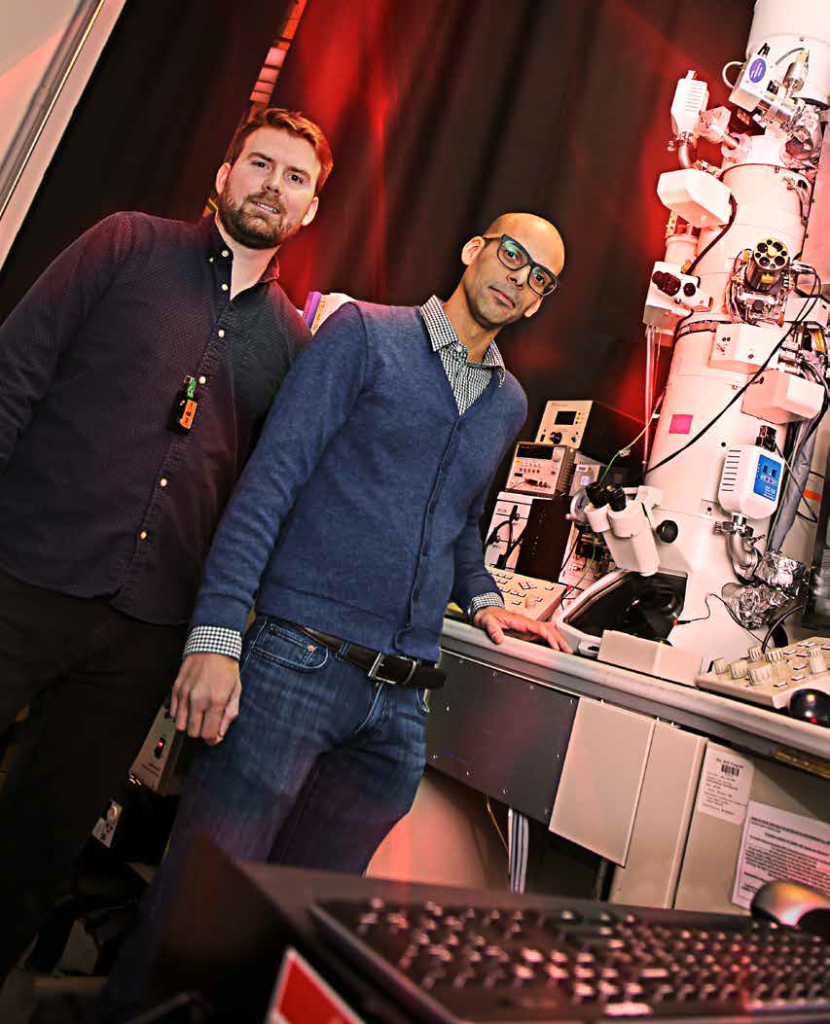

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign professors and students have been working with a team of scientists at Sandia National Laboratories led by Khalid Hattar of the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies (CINT). They’re developing a new way to test materials at high temperatures at the nanoscale. This work ties to Sandia’s mission to advance fundamental science to promote national security and international scientific leadership. The University professors were able to run experiments with their students and Sandia researchers on specialized equipment available at CINT.

This collaboration was possible because the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign is a valued Alliance partner in Sandia’s University Partnership Network, an initiative Sandia has formed with universities to promote collaborative research and attract top talent to work on tough problems.

Solution

In order to test the materials, two types of experiments were combined together in a transmission electron microscope (TEM): laser irradiation to heat the sample and compression to create stress.

The tight focus of the laser allowed the researchers to heat the samples to over 2000° C without overheating the microscope. This innovation let researchers capture time-lapse images of the experiments, which are helping scientists better understand how materials respond to high temperature processing or environments in varied applications.

Impact

This new testing method can help engineers design stronger, safer mechanical parts. After the University and Sandia researchers ran experiments on ceramic materials and published papers, follow-on studies focused on more complicated materials like tungsten and depleted uranium. Parts that are used in systems as varied as light bulbs, spacecraft cladding, and nuclear reactors all undergo high temperatures and stress.

All of the materials these parts are made of, and more, might be improved by studying them at the nanoscale in environments that replicate their use in the real world.