A sensor developed at Sandia promises a more precise way to protect cancer patients, radiologists and even American military from harmful radiation.

Sandia researchers Patrick Doty and Isaac Aviña have designed a flexible, disposable radiation patch, a wearable dosimeter that can be manufactured quickly and reacts immediately when it detects radiation.

Body of work

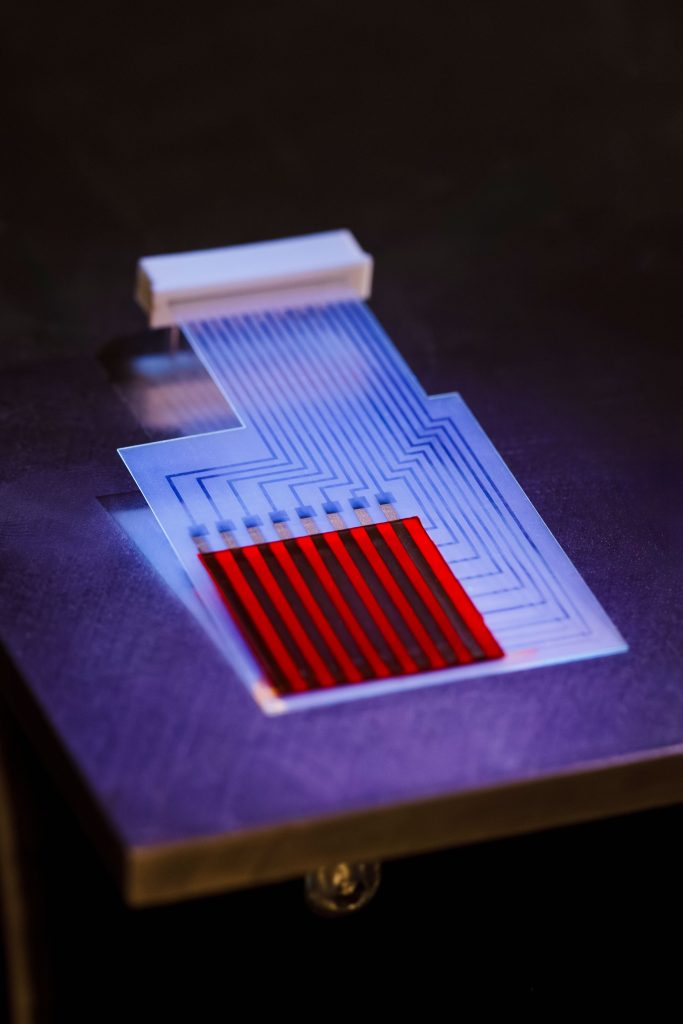

Film dosimeters have been used for decades as badges that change colors after radiation exposure, but they cannot show exactly when or where exposure happened. Patrick and Isaac took that idea, combined it with new light-sensing polymers and microelectronic grids, and designed a disposable, flexible patch that can show, in real time, where radiation is entering a body. The concept quickly drew interest from medical professionals trying to better target cancer treatments.

“That’s where Patrick and I started, exploring oncology,” Isaac said. “There was a lack of accuracy and precision when it comes to radiating tumors. There was no way to detect in real time where the radiation was going into the body and how much was being delivered to the patient.”

Along with measuring dose, hitting the tumor and not nearby healthy tissue has been a long-standing challenge.

“Pinpointing it so that it hits a cancerous tumor is even harder,” he said. “Right now in the medical world, we aim beams at cancerous cells, with a wide range of error, meaning that sometimes we leave large parts of cancerous cells and other times we hit healthy tissue. To fix this problem, we need better accuracy.”

Motivated to innovate

The pair focused on proton radiotherapy, a form of radiation treatment often used for hard-to-treat cancers. According to the National Institutes of Health, doctors use a beam of protons to irradiate and kill cancer cells. Patients typically receive treatments several times a week for four to six weeks.

But a 2022 NIH study found that it is difficult to ensure radiation goes only where it is needed and that “children are particularly susceptible to late adverse effects of radiation.”

“I found out that with this radiotherapy, there is no in vivo dosimetry,” Patrick said, referring to measuring radiation inside the body during treatment. “They know exactly what the beam current is and what the energy is, so they know exactly where it’s going in XY space and where it’s going to stop in a tank of water. But what they don’t know is where the patient is. They might breathe or move.”

Both researchers have had close family members who faced cancer and its treatments’ side effects. That personal experience helped drive their work, and especially for pediatric patients.

“They have to put these kids under general anesthesia because they’ll move and then bring them back 30 times and do it all over again, which is horrible,” Patrick said. “Kids are smaller, so everything needs to become a lot more precise and accurate. I’ve had oncologists tell me that if there’s some really at-risk structures that they’re concerned about. They will put a film dosimeter there only to find out after the fact if they didn’t get the dose right.”

Even in adult patients, the tumors may be only millimeters or centimeters in size. The new dosimeter not only helps with aiming, it can also warn radiologists when they are off target.

“There’s the polymer that’s over a grid architecture of electrodes. Radiation comes in and interacts with the polymer. That’s happening in real time,” Isaac said. “So, it picks up the X and the Y in real time and also the dosage. The radiation then proceeds to go through the patient and hits the tumor.”

If the patient moves even a little bit, the system can react.

“They upload the prescan shape of the tumor and that becomes the boundary for the sensor that when hit by radiation, immediately lets the computer know, which can then immediately shut off the beam,” he said.

“If it’s a really large movement,” Patrick added, “there’s a safety mechanism there that can shut off the beam before it has time to harm healthy tissue.”

The right tools for the right job

Isaac and Patrick used an automated laser tool developed by Isaac and his team at Sandia California to make the patches.

“This is like a direct-write tool,” Patrick said. “You start with a blank sheet, and then you etch a pattern on there, and that’s what makes and defines the sensor pixels. Isaac makes the electrode structure that we then put the polymer on top of it. He can directly make custom patches for each application, or even for individuals.”

“We’re really agile and flexible here at Sandia,” Isaac added. “We can quickly iterate on an idea Patrick and I have one morning. We design it using my computer-aided design, and in the afternoon, take it to my laser, do my fabrication and we have something to work with. Maybe it’s going to work, maybe it doesn’t. But that laser technique is super useful to fabricate quickly.”

Copy, cut, repeat

Because the patches are relatively easy to produce, the team has made thousands of prototypes in the last few years. That level of disposable accessibility is exactly what Patrick and Isaac are refining now.

“Imagine if you took a CT scan, the doctor defined the target area, the tumor, and then you immediately upload the tumor boundary to the patch. That would be pretty cool,” Patrick said.

This Sandia innovation began drawing wider attention after they entered the DOE Energy I-Corps program.

Through Energy I-Corps they connected with FedTech, a company founded in 2015 to match intellectual property created at national labs with entrepreneurial investors. Businessman John Sanwo saw the potential.

“Patrick, John and I began collaborating, and John then launched the company WearableDose Inc.,” Isaac said. “Now we just go off to the races. We start making patches, start developing the materials, start getting it to the point that we can start to see how soon this can become a commercial product.”

That collaboration is leading in new directions.

“The next step of phase two is starting to interact with the beam itself, such that if the patient moves, the beam can also follow with the patient,” Isaac said. “So, there’s some real-life tracking to influence the direction of the beam. That requires a lot more FDA approval because at that point you’re interfering with a sensor interacting with the treatment plan in real time.”

Protecting the protectors

What started as a project with light-sensing polymers may lead to lifesaving technologies for cancer patients. But it may not end there.

“The other opportunity, besides just oncology, is protecting clinicians and technicians, even parents that are in the room, because they get a lot of exposure to radiation besides just the treatment itself,” Isaac said. “So, if your technician comes into the room and is dosing people all day long, no one keeps a count of how much radiation they are exposed to. Could you stick a patch directly on a certain portion of the body that we’re really concerned about and then start to monitor that?”

This Sandia technology is so sought after that after evaluating over 2,000 global innovations, Wearable Dose was honored with Top Global Innovation of the Year at the MedTech World Awards in November.

The technology also holds considerable potential for the military and first responders. The research team has garnered new funding from the DOD Defense Threat Reduction Agency to investigate how the patches can help service members — providing improved situational awareness and new ways to monitor exposure in hazardous environments. This translates to improved military readiness, national security, and health outcomes for today’s military and crisis responder.

Bottom line, top of mind

“We’re making a disposable patch that ensures real-time accuracy and precision for cancer treatments for patients. That’s what is really novel about what we’re doing. It doesn’t involve a vacuum to manufacture or high-temperature processing. You can make solutions and create them,” Isaac said. “My child has a medical condition with his heart and had to spend a lot of time in the hospital over at Stanford. I was able to see firsthand how these pediatric cancers really impact the child as well as the families in ways that are difficult for everyone involved. It’s particularly traumatic for children. We wanted to see how we can help mitigate some of that where they’re not having to stay at the hospital for months and months on end. Being able to have something that’s impactful and provides a solution is a big motivation for me.”

“We know these people. They’re our families and friends,” Patrick said. “Everybody should want to do something about this. What we’re doing just happened to fall in that direction, and of course we want to run with it.”