Fabricating components for critical applications often requires lightweight metal alloys that can be precisely formed into complex shapes. Yet, they must have sufficient strength to hold those shapes and remain sound under significant stresses and loads.

Understanding and accounting for an alloy’s behavior under various stresses — its plastic anisotropy — is crucial when designing for the alloy’s use in critical applications such as aerospace or automotive parts. Understanding plastic anisotropy is necessary for precise manufacturing, particularly in the forming of sheet metal. Accurate predictions of plastic anisotropy ensure that components are manufactured to meet design specifications and performance requirements.

The work of understanding a given alloy’s plastic anisotropy has always been time-consuming and expensive, especially when using experimental characterization techniques. Recent advances in computational mechanics and numerical frameworks have enabled approaches that yield accurate predictions but still require significant computational resources and deep technical expertise. A gap remains between R&D and the production floor, where manufacturers require efficient and user-friendly solutions that can accurately predict this behavior.

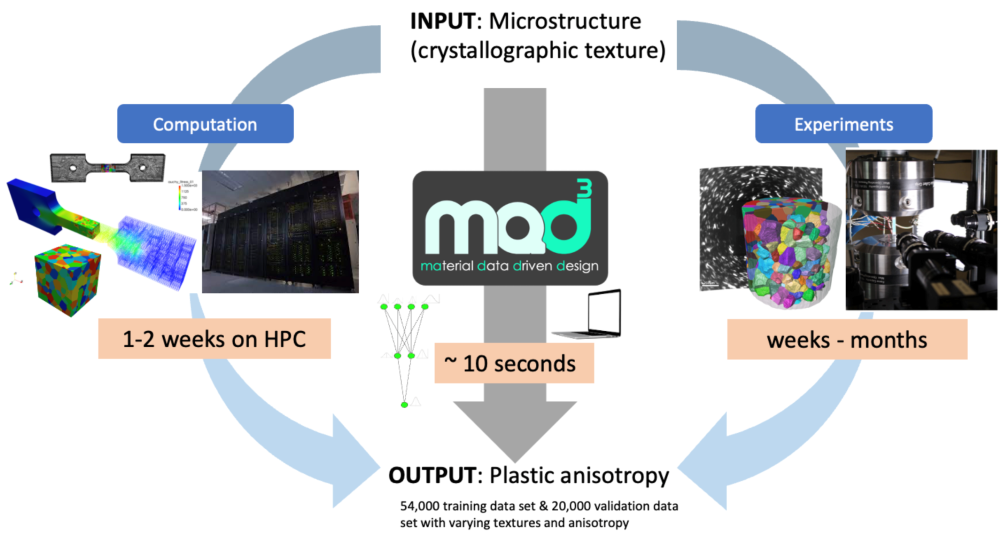

In the last 5 years, a team of Sandia researchers has sought to fill that gap. The team used the Labs’ high-performance computing resources to develop machine learning software that radically accelerates the prediction process. The software, Materials Data Driven Design, or MAD3, uses machine learning techniques to extract the alloy’s polycrystalline fingerprint — its microstructure — and accurately calculate the plastic anisotropic behavior of the alloy, which can then be used to predict the material’s expected behavior through computational simulations of manufacturing processes such as metal forming and stamping, shown in Figure 1.

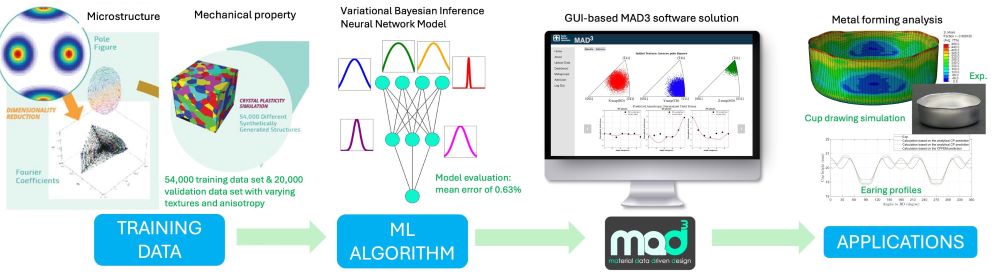

The MAD3 team developed the software’s machine-learning algorithm using a deep learning approach based on artificial neural networks. The approach is ideal for identifying complex patterns in large volumes of data that capture multiple characteristics. To enhance the tool’s predictive capabilities, MAD3’s algorithm also employs variational Bayesian inference, a computational technique designed to account reliably for uncertainties in the data.

Training and validating this algorithm were resource-intensive, involving more than 70,000 datasets in total and requiring the use of Sandia’s HPC Eclipse and SOLO computing platforms. Figure 2 schematically depicts the knowledge extraction process. The learning model was trained on results from 54,000 high-fidelity crystal plasticity simulations, then validated by predicting the plastic anisotropy of 20,000 new structures to which the model had never been exposed. The mean error across all “test” structures was less than 1%. The fidelity of the underlying deep learning model has been further validated with experimental and computational data.

The software also brings the needed computing resources out of the research lab and places them within reach of the production floor. The solution’s intended users include engineers in the automotive and aerospace industries as well as research institutions and laboratories where quality control and assurance are essential in manufacturing and forming processes. For those end users, MAD3 bypasses the need to perform experiments or run complex and computationally expensive high-fidelity simulations.

MAD3 implements a user-friendly interface deployed by a web-based application. After opening the application, the user loads files describing the internal structure of a metal alloy. Typically, this is crystallographic texture information data obtained from X-ray diffraction or electron microscopy. MAD3 instantly processes the input file and leverages a pretrained deep learning model to analyze the material’s internal structure and predict the material’s anisotropy.

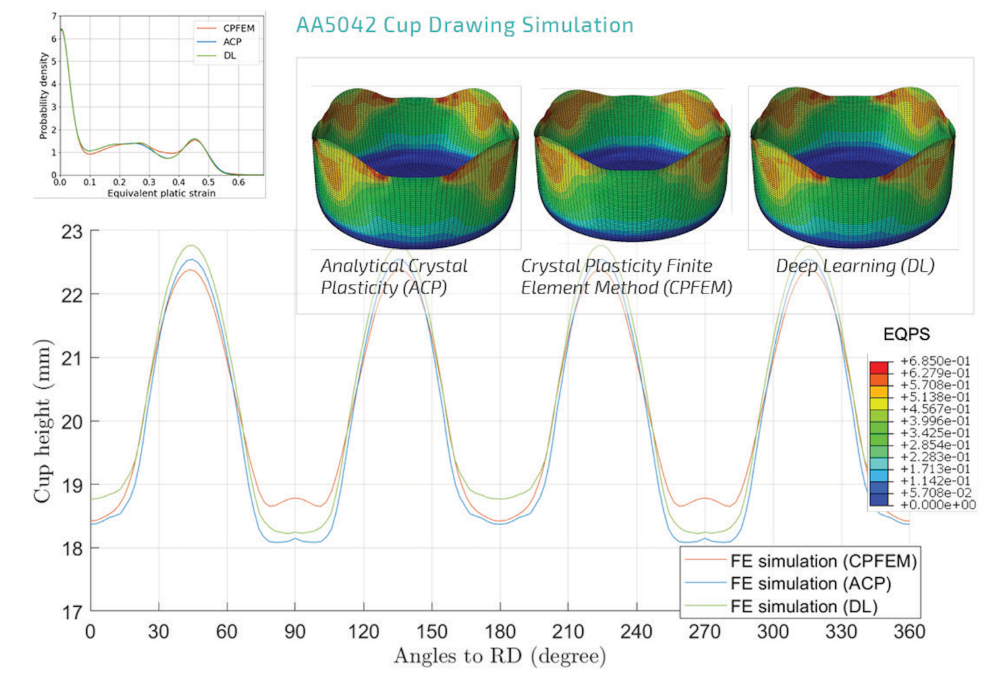

The software has been validated with many materials in several research projects. Figure 3 compares cup-drawing simulations performed using plastic anisotropy parameters obtained using MAD3. The peaks and valleys on the rim of the cup after being drawn are called earing profiles and are caused by the plastic anisotropy of the metal. Notice that the predicted earing profiles obtained by MAD3 show excellent agreement with experiments. It is important to note the parameters were obtained 1,000 times faster, without any high-performance computing resources; they were obtained using a regular laptop.

The MAD3 software solution will enable rapid development of new parts and materials with tighter performance margins as well as improved processing routes to obtain optimal microstructures. Enabling such rapid development will advance the design and manufacturing of lighter structures in automotive and transport areas, optimized military vehicles and structures, and alloys for energy applications.