For over five decades Moore’s law — the empirical trend of the number of transistors on a chip doubling every two years — has powered the growth of HPC systems. While this has provided an exponential growth of compute power, such a growth in scale has also made systems increasingly susceptible to hardware faults and errors.

Today, HPC systems are composed of far more hardware components than those of decades past — components that are increasingly intricate and require increasingly sophisticated manufacturing technologies. Consequently, a myriad of factors induce hardware faults across a full-scale system in operation, which can adversely affect its overall reliability. These factors include cosmic radiation, manufacturing defects, thermal and electrical operational stresses, and more.

Such faults either produce an incorrect result, despite no programming errors, or cause frequent interruptions, and severely hamper the productivity of system users. These faults are typically random, and their statistical behavior has been observed to vary in time and across components; the same component can get more or less fault-prone as time goes by, and similar components in a given system can have different fault behaviors.

Hardware vendors provide some fault protection mechanisms, but these are insufficient and unable to prevent all types of faults over the lifetime of a system. Numerous studies have retrospectively examined monitoring data and logs of HPC systems to glean statistics and trends of hardware faults, but factors affecting system reliability are not well understood, and future trends are impossible to predict. All the while, HPC system users incur a hidden cost from grappling with fault-prone hardware — either in terms of more resource usage for solving a problem, a longer time to solution or both.

Fault tolerance is an area of research that develops techniques for dealing with hardware faults; accepting them as a fact of life, fault-tolerance techniques aim to mitigate the cost incurred due to hardware faults and ensure an overall efficient and cost-effective use of an HPC system. Even systems designed for large-scale AI workflows are susceptible to faults and fault-tolerance since AI is an active research topic.

However, the consequence of hardware faults can be more severe for mission-critical scientific calculations. Through algorithmic and software-based approaches, fault-tolerance imbues computations with mitigation strategies to detect and recover from hardware faults with minimal overhead. This allows a calculation to continue in the face of hardware faults, which would otherwise have to be interrupted or repeated. Either can be costly.

Scientific applications solve large problems by dividing them and assigning each subset to different nodes that compute the solution in parallel. The nodes communicate with each other, exchanging data as mathematically or algorithmically necessary for the parallel solution.

One class of hardware faults that are challenging to tackle are hard or fail-stop errors, faults that cause a crash on one node and terminate an otherwise stable computation on all nodes. Many factors can culminate in hard failures, but the ensuing abrupt termination on all nodes can undo progress, which can be expensive in terms of lost computational cycles.

The dominant paradigm of parallel computing, message passing interface (MPI), is particularly vulnerable to hard failures as it has had no systematic way to respond to a node failure. Only recently, a fault-tolerance specification — user level fault mitigation — was admitted to the standard. As the name suggests this mitigation provides only basic functionality to deal with hardware failures, leaving much of the recovery actions up to the user; it prevents a total fail-stop of the computation and allows repairing the communication infrastructure, but the bulk of the recovery is left to the user to implement.

Sandia researchers developed FENIX, a software library that provides seamless and transparent recovery to enable MPI-based applications to recover from hard faults and be more productive for users of HPC systems.

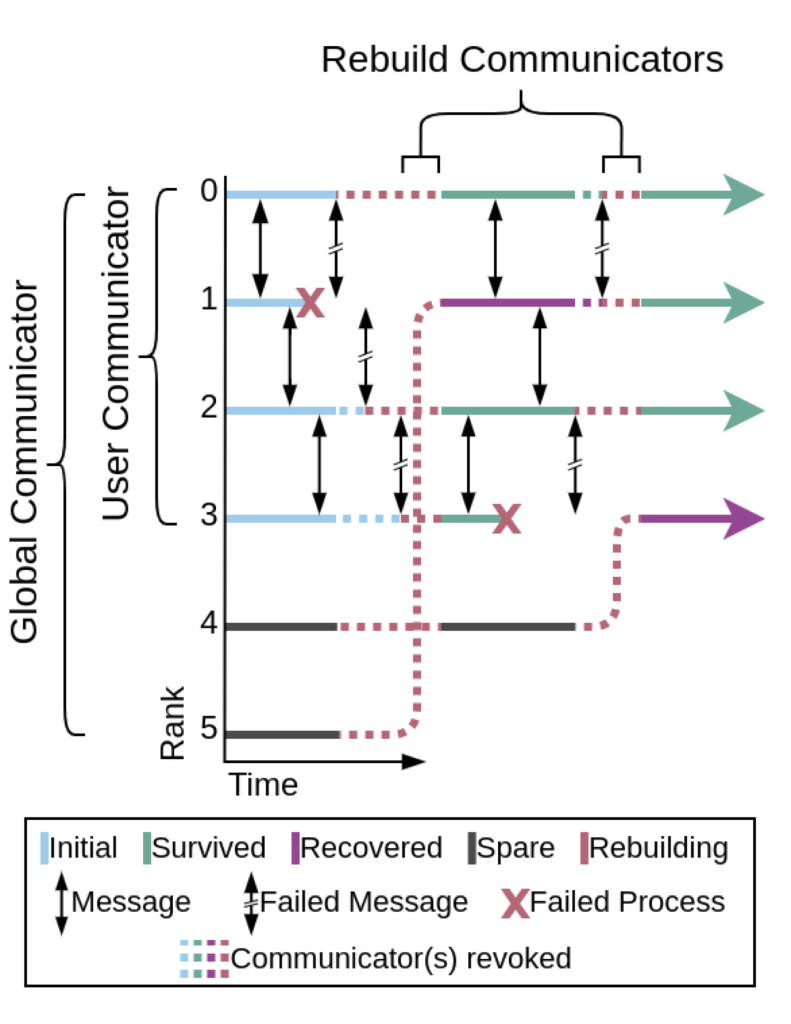

Before FENIX, an application would terminate upon encountering a hard fault and exit the job queue. FENIX enables applications to continue running with minimal interruption and not have to re-queue their job, reducing time and resources used. FENIX provides simple and intuitive mechanisms for transparent online recovery. Applications add FENIX function calls to existing codes to specify the process and data recovery mechanisms. Process recovery replaces the failed compute node, typically with a spare node that is requisitioned at the start and kept on standby. Data recovery involves the application periodically checkpointing its solution, so when a node fails, the spare node can fetch the solution state from the checkpoint and resume. Applications need minimal changes to codes to implement calls to the process and data recovery functions, and FENIX orchestrates the recovery. Figure 1 illustrates an example of FENIX-enabled recovery of a simulation with four active nodes that encounter two failures.

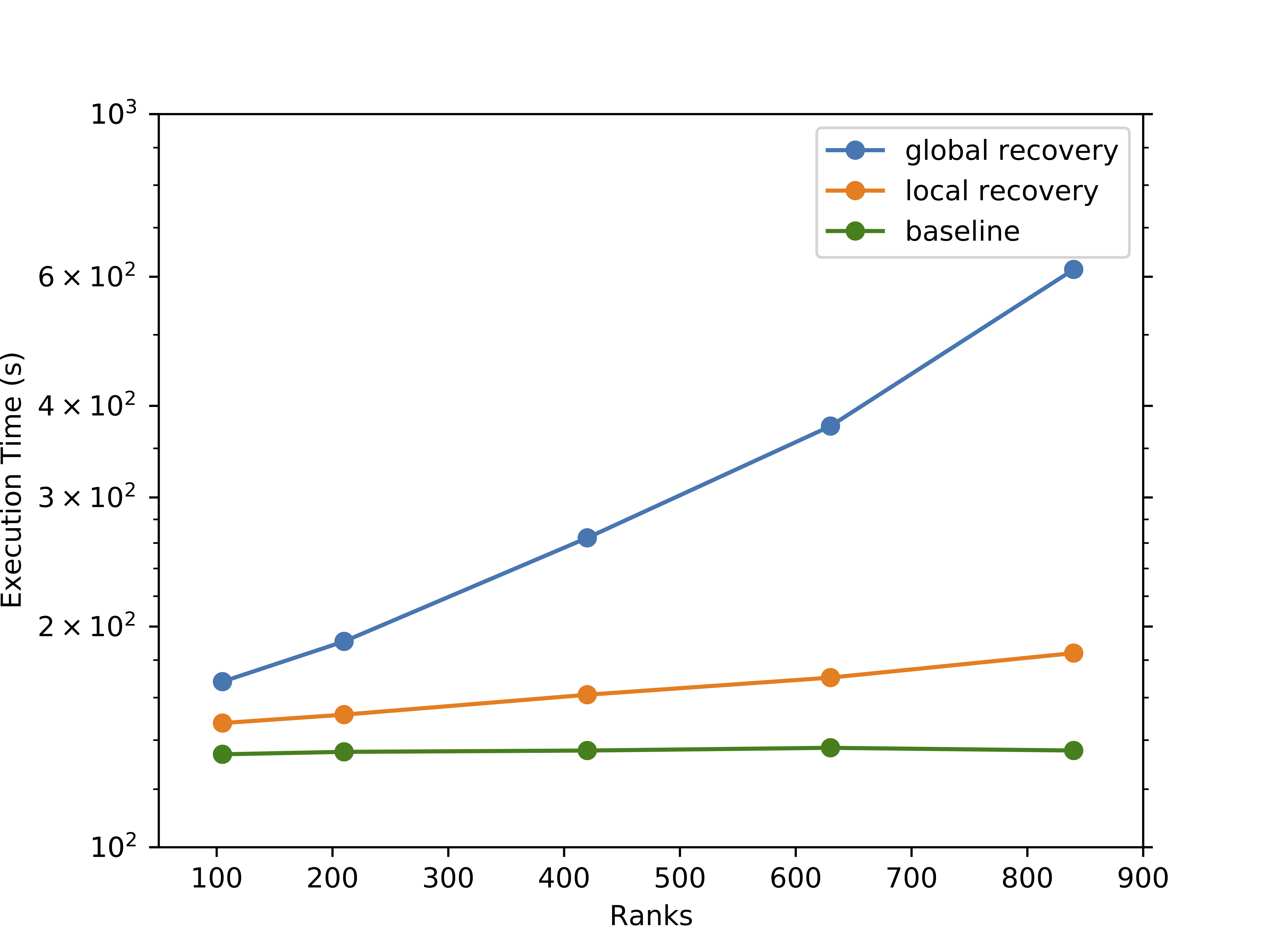

To demonstrate recovering from frequent hard faults, Sandia researchers with the University of Tennessee used a prototype application: a stencil solver. The stencil solver demonstrates the concept of local recovery; upon encountering a failure, only the recovered node repeats any necessary computation from the last checkpoint, while the survived nodes do not. This contrasts with global recovery — the de facto method — in which all nodes roll back to the last checkpoint after a failure and resume.

Consequently, global recovery forces nodes unaffected by the failure to needlessly repeat computations and becomes exponentially expensive as failures increase. Local recovery in comparison scales linearly with the number of failures. Significant design changes and improvements were made in FENIX and MPI-ULFM to handle frequent faults as part of the demonstration. Figure 2 shows results from runs on the Kahuna cluster ranging from 4 nodes (112 MPI processes) to 32 nodes (896 MPI processes). Local recovery tolerates failures with marginal overhead, whereas global recovery takes orders of magnitude longer to complete. At the largest scale, the runs recovered on average from up to about 100 failures, which demonstrates the robustness of FENIX and MP-ULFM. Efforts are underway to make LAMMPS fault-tolerant for simulation campaigns on ATS systems Crossroads and El Capitan.