Sandia National Laboratories’ researchers frequently use the advanced fire simulation capabilities in engineering mechanics code suite Sierra to predict the heat loads to components in accident scenarios involving fuel or composite fires. The results of these simulations are used, along with experimental data, to support safety assessments and qualification efforts for various weapon systems; however, performing these simulations at a high enough resolution to provide credible predictions often requires using thousands of CPUs on the Department of Energy supercomputers for weeks to months. To speed up this process, the Sierra/Thermal-Fluids team has updated their Sierra/PMR and Sierra/Fuego codes to run on next-generation GPU systems, reducing the time and cost of the simulations while also enabling larger and more accurate simulations.

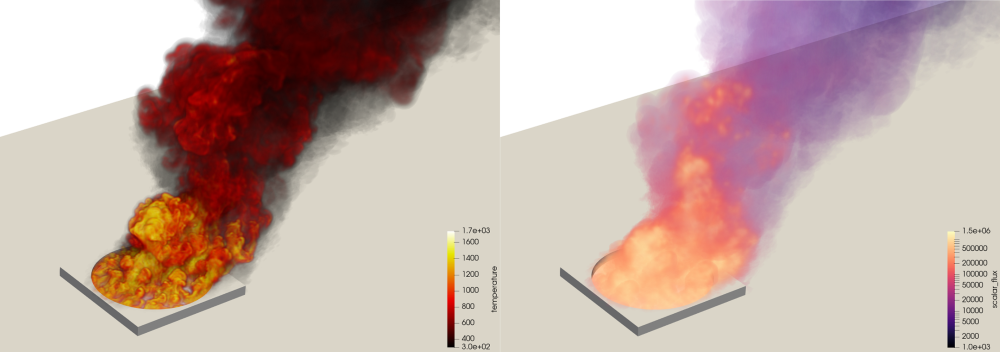

Figure 1. Simulation of a 5-meter diameter methane pool fire with no crosswind run on 64 H100 GPUs

Researchers must consider accidents involving fire when assessing the safety of transporting or storing of nuclear weapons. Depending on the details of the accident environment, different fuels and ambient conditions are considered, such as the presence of a fuselage or trailer in the accident, fuel type, and atmospheric conditions. All of these factors strongly impact the fire dynamics and dramatically modify how much the weapon is heated by the fire. Simulations of this scale, such as the one shown in Figure 1., help provide descriptions of these conditions but used to require weeks to months calculate.

Fire simulations require several components. They use a computational fluid dynamics framework to model the movement of air, fuel, and combustion products in and around the fire. Modeling the complex chemical kinetics in a fire environment can be expensive, so these simulations use pre-tabulated, reduced-dimensional flamelet models instead of solving the chemical reaction problem at every point in the domain. Participating media radiation (PMR) is also important to capture for not only the heating of an object in the fire but also for the heat loss from the flame and radiative heat transfer between different parts of the flame, largely due to the development of carbonaceous soot. These components all add up to an expensive simulation, which makes it hard for researchers to run necessary grid refinement studies or perform large-scale verification with experimental data.

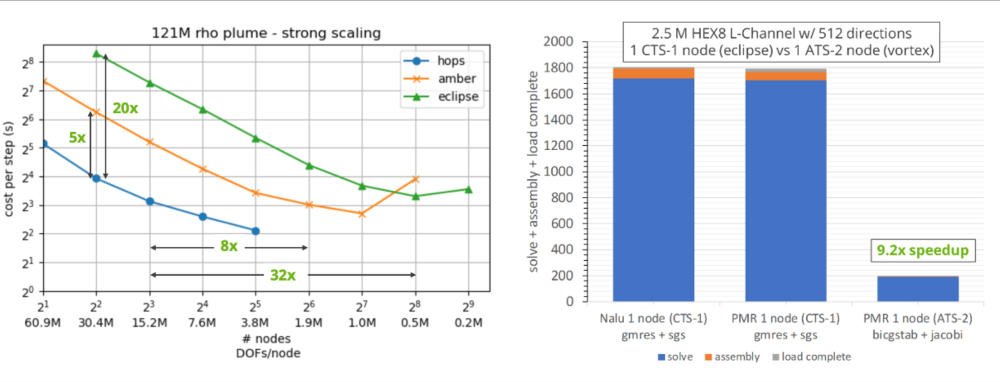

In recent years, the Sierra/Thermal-Fluids team has developed a new PMR code (Sierra/PMR) that was designed from the ground up for fast simulations on next-generation computing hardware using GPUs. The new PMR code has resulted in simulations 7 to 17 times faster on a Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory GPU supercomputer called ATS-2 as compared to traditional capacity machines at Sandia like Eclipse, called CTS-1. It also provides up to two times the speedups on conventional hardware, such as CTS-1, relative to the former PMR code capability in Sierra, as seen in Figure 2. Using newer generation GPUs like the H100 series on the Sandia Hops system, these codes have been able to reach up to 20 times faster simulation times compared with Eclipse.

The team then used the design patterns from Sierra/PMR to make similar updates to the legacy Sierra/Fuego CFD fire modeling code. Instead of rewriting the Sierra/Fuego CFD code, the team used an incremental migration approach to get the fire simulations running on next-generation platforms. Since a fire simulation needs to run both PMR and CFD capabilities simultaneously (Figure 3), converting both codes to run on the GPU was necessary to get good end-to-end simulation times. The team relied heavily on Sandia’s Kokkos performance-portable software library for this work, which allowed the converted algorithms to run not just on the current machines but also on the new computing platforms, like El Capitan also called ATS-4, with minimal additional development work.

By converting both Sierra/Fuego and Sierra/PMR to run well on GPU platforms, simulations that once took months can now be completed in days. These speedups not only reduce the end-to-end turnaround time but also enable higher simulation throughput by allowing multiple concurrent simulations per node for faster verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification simulation ensembles that fire scientists often need to run to make credible predictions.