Sandia researchers design liquids to selectively trap methane from manure and food scraps

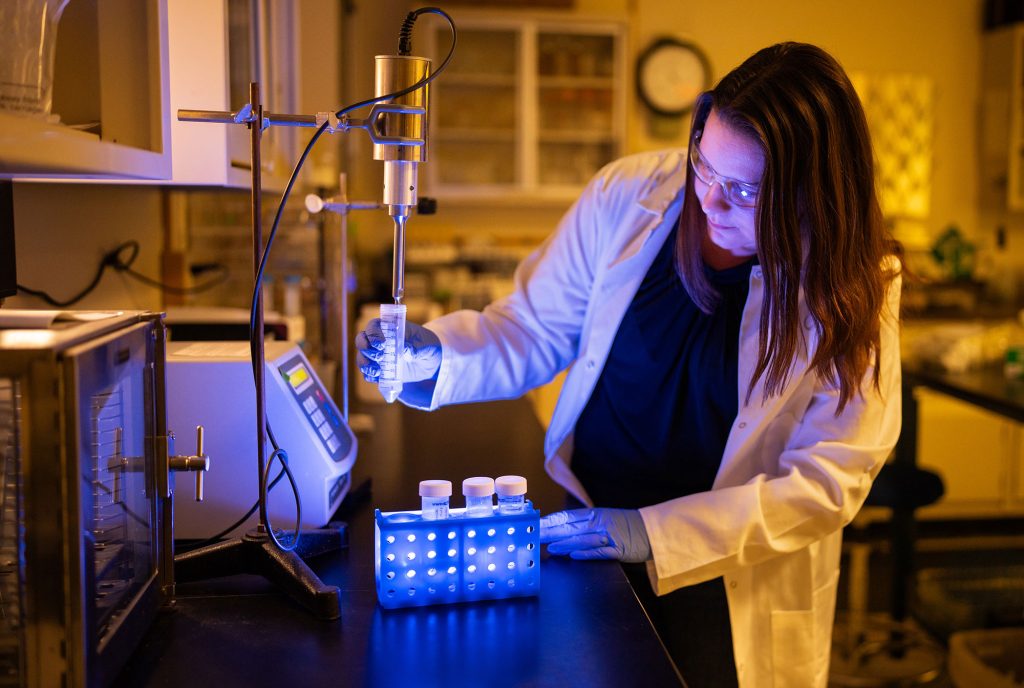

Jessica Rimsza, a materials engineer at Sandia, sees untapped potential in what most people see as waste.

Food scraps, manure and sewage are natural byproducts of the U.S. agricultural industry. They are also rich in biogas, a mixture that contains methane and other valuable chemicals. Jessica and a team of researchers at Sandia are developing chemistry that could help capture methane from biogas and separate it from other gases so it can be put to good use.

“We are creating new types of porous liquids that can selectively capture methane and other gases,” Jessica said. “This could provide a supplemental domestic energy source to support U.S. energy independence.”

The technology could one day support biogas capture at places like wastewater treatment plants, agricultural operations and other facilities that already generate biogas but may not have efficient ways to separate and upgrade it.

A liquid with built-in empty space

A porous liquid is a liquid solvent combined with a porous solid material — a combination that essentially creates a liquid full of tiny cavities. Those cavities create empty space inside the liquid, allowing it to absorb and store gas molecules.

The porous solids can range from traditional materials such as zeolites or newer, highly tunable structures such as metal-organic frameworks, covalent organic frameworks and porous organic cages. By mixing different solids and solvents, researchers can tailor how the liquid behaves.

“Gases dissolve in liquids all the time. As I like to say, that’s why fish can breathe,” Jessica said. “There’s dissolved oxygen in the water. With porous liquids, we are adding a solid material with free space into the liquid, and when we preserve that free space, dissolved gases get into the material.”

The team has created dozens of different porous liquids so far, and many more combinations with varying properties are possible.

“There are hundreds of thousands of porous materials and there are tens of thousands of solvents, so there’s a vast untapped number of possible combinations from which to form porous liquids,” Jessica said. “Even if a vanishingly small fraction of those end up being useful, that could still be thousands and thousands of potential good combinations.”

Separating methane from the mix

Jessica’s current focus is porous liquids that can selectively capture methane from biogas, separating it from carbon dioxide and other impurities.

“The gas needs to get from the air into the solvent, and then it has to go from the liquid into the empty space inside the pores,” she said. “That gives you a lot of different options to select what gets captured. It’s like having levels of sieves on top of each other.”

After capture, methane can be released from the porous liquid and used for electricity generation, heating, steel and glass production and other residential, commercial and industrial applications. It can also serve as a feedstock to produce hydrogen, methanol, ammonia and acetylene — chemicals used in fertilizers, plastics and other products.

In earlier research, the team designed porous liquids capable of selectively capturing carbon dioxide, which can be used in soft drink manufacturing and other applications.

Jessica said the liquid form could make the technology easier to integrate into existing infrastructure.

“As a liquid, they can be used in existing piping, unlike solid porous materials that would require specialized handling and setup,” she said.

From theory to today’s research

Porous liquids are a relatively recent discovery. Jessica said they were first theorized in 2007 and proven in 2015. Sandia’s research has focused on expanding the possibilities of these materials for energy applications by characterizing their behavior and studying new combinations targeted for high gas absorption capacity and selectivity.

The researchers are also studying how much gas porous liquids can capture. The team has found that in some formulations, porous liquids can hold more gas than either component typically would on its own.

For example, Jessica said a typical solvent may have space for about 1% gas and a porous solid may have room for up to 80%. When the two combine into a porous liquid, the material can capture far more gas than expected based on a simple linear calculation, even when only 10% of the weight of the porous liquid comes from the solid material. In some cases, up to 40 times more gas can be dissolved in the porous liquid than expected. Jessica said that effect can multiply the gas capacity of the solvents.

The team has submitted a broad patent covering the definition and design principles of porous liquids and has published journal articles on many facets of the research. The DOE Office of Science Basic Energy Sciences program and Sandia’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program fund the research.