From fusion energy research to Ironman racing

By Magdalena Krajewski

Most people might try to run a full marathon or attempt a century ride before signing up to do both on the same day after swimming 2.4 miles, but Mary Alice “Mac” Cusentino is not most people.

In her work at Sandia, Mac’s research focuses on how materials could be used to one day create fusion energy. “I’m trying to take the sun and put it into a box made of materials that we find on Earth,” she said.

In other words, Mac enjoys a challenge, and that drive to push herself started early.

In 2008, Mac was a freshman at the University of Wisconsin when she decided she wanted to do an Ironman. At the time, she was just getting into running but wasn’t much of a swimmer or cyclist.

“I like to push myself to the limits and see what I’m capable of,” she said. “Competing in an Ironman seemed like the most extreme kind of race, so I decided that’s what I wanted to do.”

140.6-mile north star

Mac didn’t go full Ironman right away; instead, she set that as her north star and started with an Olympic distance triathlon.

A full Ironman is a long-distance triathlon that covers a total of 140.6 miles. It starts with a 2.4-mile swim, followed by a 112-mile bike ride and concludes with a 26.2-mile run, also known as a full marathon. An Olympic distance triathlon, also known as a standard distance triathlon, consists of just under a mile swim, a 24.85-mile bike ride, and finally, a 6.2-mile run.

“I signed up for the Olympic distance race as kind of a teaser, just to try it out,” she said. “Come race day, a bunch of things went wrong.

“I was a terrible swimmer and was super nervous about the swim. We were in Lake Zurich in the Chicago area, and the water was really dark and cold. In the first ten minutes, I got lost on the course, and kayakers had to steer me back to where I was supposed to be swimming,” she said. “I was one of the last people out of the lake, and there were barely any bikes left. I got on mine and felt pretty good, but then I was going downhill and got a flat tire. Luckily, someone stopped to help me, but it was definitely not going great.”

But then came the run, and Mac said she found her stride.

“I saw my family at the finish line and just got this rush of pride like, ‘Wow, I just did that,’” she said. “I was pretty amped up to do it again, push myself and see if I could do better.”

The next year, Mac competed in her first full Ironman, and since then, she’s completed eight full and seven half Ironman competitions. That’s 1,779.48 miles covered — and that’s just on race days.

The hardest race

Competing has taken Mac all over the country and into all kinds of temperatures and terrains, from sweltering heat and humidity in Tennessee and Florida to drier lands in Arizona and Colorado.

“My hardest race was in St. George, Utah, in 2022,” she said. “The course was super challenging with over 7,000 feet of elevation gain on the bike and 1,200 feet on the run. On top of that, the conditions that day were awful. It was unseasonably warm, and the winds were intense.

“Around mile 90 on the bike, you have this 1,000-foot climb. I remember coming down on the other side and having never seen so many people sitting on the side of the road, waiting to get picked up.”

Mac said this race had a 20% Did Not Finish, or DNF, rate. The average DNF rate for a full Ironman race is 10–15%.

“After I got off the bike, I sat down and thought, ‘How am I going to run?’” she said, referring to the marathon up next. “I finished; it took me 16 hours, but I finished, and that felt pretty great.”

Small wins add up

Not all races are as challenging as St. George, but Mac said every Ironman is a challenge.

Like her work in fusion energy, Mac sees each race as a series of incremental wins.

“The joke is we’re always 20 years away from creating a viable source of fusion energy, but we’ve been saying that for more than 20 years,” she said. “Without an actual finish line in sight, it’s the incremental improvements we’ve made that bring me a sense of accomplishment.

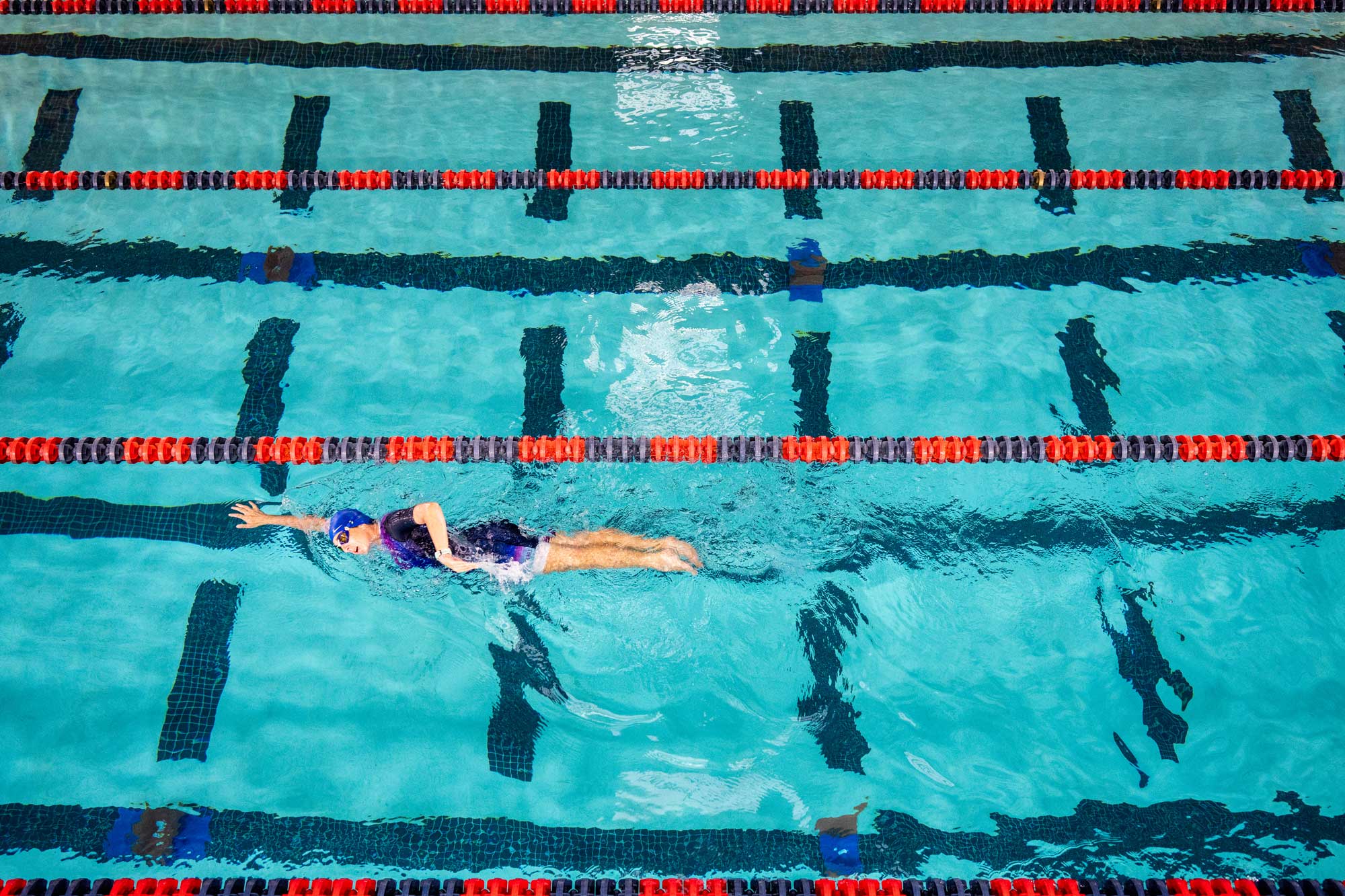

“And I use that mindset when I get ready for a race. 140.6 miles is intimidating to think about as one block, so I break it up, each chunk being its own little accomplishment that brings me closer to the finish line,” she said. “When I’m swimming, I focus on getting to where the buoys change color, which means the swim is halfway done, and I’m that much closer to my favorite part, the bike. That’s where I get to enjoy the scenery, let my mind wander, and sing whatever song I have stuck in my head. By the time I get to the run, I’m tired, so I divide 26.2 miles into smaller races: a half marathon, a 10K, a 5K. It’s basically a collection of small wins I can celebrate along the way.”

Doing hard things

Mac’s Ironman journey has run parallel to her educational and professional one — from undergraduate school to earning her doctorate, starting at Sandia as a postdoc in 2018, and now being a principal member of the technical staff. Both paths have been undeniably challenging, but doing one hard thing alongside, yet separate from, the other has helped her with both.

“Knowing that I can do something really hard, like complete an Ironman, has given me the confidence and perseverance I’ve needed to push through other challenges in school and in my work pursuing fusion energy,” she said.

Mac went from being a casual runner to having 17 triathlons under her belt.

“I skipped ahead,” she said. “So now when I think about what’s next, most races feel like less than I’m capable of.”

Today Mac has her sights set on a new north star, a 50-m