Years before Osama bin Laden executed the world’s deadliest terrorist attacks, Sandia researchers were studying what made the US vulnerable and where threats to US security in a post-Cold War world were likely to emerge. Among these researchers was Gary Richter (8112), a systems analyst who evaluated the goals and capabilities of terrorist groups. In a 1999 case study, he concluded that bin Laden was a significant threat who "taps a bottomless reservoir of ethnic and religious discontent and funnels it against the US." As it turned out, Gary was right.

Weeks before 9/11, Sandia and KAFB were discussing creating an open campus by removing the fence around TA-1 now that the Cold War had passed. That discussion ended with the 9/11 attacks.

* * *

American Airlines Flight 11 tore into the World Trade Center at 6:46 a.m. in New Mexico. About five minutes later, then-Labs Director Paul Robinson, who was at home getting ready for work, heard the first televised report of the tragedy.

From 1985-1988, Paul had worked on the 93rd floor of the south tower. He recalled that one of the job’s perks had been a car and an underground parking spot, where he very well could have been during the 1993 truck bomb attack had fate not interceded in 1988 by having him leave New York to lead the US delegation at the US-Russian Testing Talks in Geneva.

This second set of attacks was clearly far worse. “You couldn’t help but think what might have been. It was horribly shocking,” Paul says. His thoughts quickly turned to the day ahead. “I headed into work because I knew we were going to be busy. I got calls at home and on the way in.”

* * *

Gary was in Albuquerque for a conference when he heard the news. He was glued to the television when United Airlines Flight 175 hit the south tower at about 7:03 a.m. in New Mexico.

“I had this feeling of helplessness,” he says. “I’m employed by a national security laboratory to study these things and right now at this hotel I can do no more than my own mother could do. I dedicated most of my life to fighting people like this; it’s been my career, so it made me sad that I couldn’t do anything right then.”

* * *

An hour-and-a-half after the first plane hit, Paul says Gen. John Gordon, then-head of NNSA, called to ask for Sandia’s help.

“‘You guys are the ones who have been working counter-terrorism the hardest,’” Paul recalls Gordon saying, “‘Get some guys back here to help me handle all the requests we’re getting, and the communications with all the other labs and sites.’”

Paul agreed to send a Sandia-led team to Washington, D.C., as soon as possible. He was unaware at the time that the Federal Aviation Administration already had made the decision to ground civilian air traffic.

Within hours of the attacks, the questions started. People remembered Sandia’s past research, particularly a video of an F-4 Phantom crashing into a structure similar in strength to nuclear reactor containment vessels. The video took on new significance that day.

“Almost instantly, all around the country, in lots of organizations, people remembered that work,” Paul says. “They were asking Sandia, ‘What’s the vulnerability of this facility and that facility?’”

A phone bank normally used for VIP visits was set up in the director’s office to handle the mass of phone calls.

To help get answers, Paul phoned Tom Bickel (2200). The then-director of Engineering Sciences had used structural mechanics calculations to predict damage caused by aircraft hitting various structures.

Paul also organized focus groups of researchers who worked for Dennis Miyoshi, the director of Security Systems and Technology at the time.

“One of the focus groups’ ideas was spectacular; an example of Sandia engineering that offers simple, elegant solutions,” Paul says. The group advised using steel cable, properly tensioned and anchored, to throw back any vehicles that attacked areas containing critical buildings and personnel.

There was never any explicit threat to the Labs, but Paul says those in the director’s office were working on so many issues that they “were almost unconscious of what was going on outside.” That job was left to others.

* * *

Wes Martin, protective force chief of operations, heard about the first plane hitting the World Trade Center when he left home. By the time he arrived at the office, word came that a second plane had hit and he knew this was no accident.

Wes says Sandia aligned with Kirtland Air Force Base to elevate the Force Protection Condition to “Charlie plus,” which describes a situation where actions are taken because terrorist activity is imminent plus additional security measures were put into place as if Sandia were under attack.

At 10 a.m., just more than three hours from the first attack, nonessential Sandia employees were told to go home.

“There was a flow of people leaving,” Wes says. “It was not an insane rush. People left in a very organized manner.”

By 2 p.m., the base was virtually empty and Sandia’s Leadership Council met to establish who was required to report for work and figure out how to get people back.

The Emergency Operations Center was concerned about the state of Sandians who were on travel and scattered all over the world, particularly those at the Pentagon, which was also attacked that morning, killing 125 people on board the aircraft that struck the building and 64 people working there.

Charlie Thomas, who was on special assignment to DOE and was at the Pentagon that morning, recalled at the time: “We felt a tremor go through the building.”

Charlie and all Sandians there and elsewhere were all right.

* * *

On Wednesday, Sandia’s laboratories and offices were nearly deserted with a lone car in a parking lot that normally held hundreds. “It was eerie,” says Iris Aboytes (3601), an emergency communicator that day. “It was like a hurry-up-and-wait atmosphere.”

Former VP Roger Hagengruber arrived at work at 4:30 a.m. and received a phone call from Gordon, asking him if he were willing to lead the Washington-bound Sandia team and describing some of the needs he already had: take a look at NNSA’s facilities, assess the risks, and look at the possibility for organized terrorist attacks and attacks using aircraft.

Sandia’s security research dated back to the mid-1970s. Sandia’s fingerprints could be seen throughout all nuclear portal perimeter monitoring systems, perimeter intrusion protection, double fencing, and other security measures and research. By the mid-90s, researchers were looking at the possibility of a terrorist attack to steal nuclear materials. Roger had been tapped by DOE in 1996 to conduct a number of security studies, including looking at the importance of dealing with the security of nuclear materials.

When rumors of substance spread after the attacks that there would be attacks on nuclear facilities, it made sense to call Sandia.

“I was working off of a very strong base of experts who knew a lot more about the details than I did,” Roger says. “And, I was ready to help take on the concern about how to deal with the security. 9/11 increased what was already a very high priority to an urgency to make sure we had done everything we could.”

* * *

On Sept. 13, a gray, rainy Thursday morning, Wes stood at the Eubank gate watching a line of vehicles waiting to return to work. Motorists handed their badges to officers at the gates for the first time and expressed their gratitude for the added security.

“We probably got more respect from the people at the gates than we ever got before that day,” Wes says.

Wes, like Roger, also viewed his job in terms of a broader sense of national security. “In there,” he said shortly after 9/11, “is where we’re developing the technology that can help us win this thing … . Our job is to get those folks into their labs and offices as quickly as possible and make sure they have a safe place to do the work this nation needs right now.”

Thursday was a busy day. Researchers say their phones were ringing off the hook. Even before 9/11, Sandia had developed systematic ways to identify security weaknesses of buildings, dams, drinking water supplies, and other possible targets. Now the nation wanted the benefits of that work.

Tom, who rode in that morning with former VP Al Romig, learned that he would be joining the team headed to Washington that day. He jokes that he had to tell Al to find his own ride home that evening.

Joining Roger and Tom was Jim Larson, then a manager in what later became Critical Asset Protection and Security. The men gathered at a corporate terminal adjacent to the Albuquerque airport, but their team wasn’t yet complete.

Roger ran into a Los Alamos lab expert, who happened to be passing through the terminal and agreed on the fly to join them. Once in Washington, they coincidentally bumped into two special nuclear material production experts from Pantex and Rocky Flats who were trying to return home, but agreed to join the team when asked.

The Lear jet they took had government clearance because civilian aircraft were still grounded.

The tiny jet departed Albuquerque alone that day, headed for Andrews Air Force Base near the nation’s capital. The passengers weren’t afraid to be alone in the sky because they were too busy discussing how they were going to carry out their work.

Over the central region of the country, the pilot called Roger to the cockpit. “The pilot said, ‘You’d better take a look at this. I’ve never seen anything like this before. There isn’t a thing in the air. It’s empty.’”

Normally the screen would have been filled with midday flights criss-crossing the country, but that day it was dark.

After landing safely, they were taken to a hotel in Crystal City, Va. As they walked across the lobby, they found the typically bustling hotel deserted.

* * *

By Thursday afternoon, Paul had worked two-and-a-half days straight and took his first break, like many other employees who worked long hours during the crisis.

* * *

At 7:30 a.m. Friday, Sept. 14, Roger and his team were taken to a high-security vault at DOE and began calling NNSA facilities, talking to security managers, making sure contingency plans for an aircraft attack and a release of materials were in place.

“We went to work every day in an environment that was the aftermath of a war zone,” Roger says.

Tom recalls: “It was very chaotic.”

They looked for vulnerabilities as they worked, particularly at critical facilities. “These types of attacks not only would create a nuclear incident, but they could also damage our nuclear program,” Roger says. “We looked at events that would cause death or exposure to significant amounts of radiation, that would cost a permanent or decades-long loss of a permanent facility or would cost billions of dollars to replace. Finally, we looked at things that could create an irretrievable loss of public confidence.”

Working 12 hours-plus a day through the weekend, the team created a matrix based on high, medium, and low risk and a list of recommendations for the facilities in what was later dubbed The 72-hour Report.

While some callers found sleepy or grumpy employees on the other end of the line, once they knew why the group was calling, they helped. Team members say everyone pitched in during the crisis.

“They were fantastic. . . . Whether it was Lawrence Livermore, Los Alamos, Y-12, or Pantex, or any of the other DOE/NNSA facilities, I saw them all come together and really, really focus. They were able to overcome any differences and everybody just focused on trying to help,” Jim says.

* * *

For the next few days, the mood at the Labs was one of nervousness, as it was across America, particularly when airlines returned to the skies. Wes says he helped respond to numerous false reports from employees. “It was jumpiness,” he says.

* * *

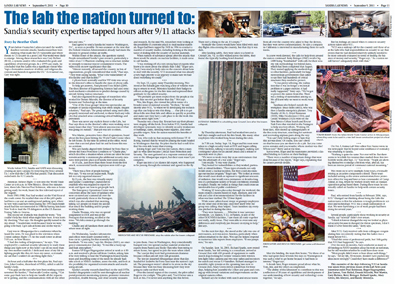

On Sunday, Sept. 16, 2001, Richard Sparks, now retired from Sandia, but still serving as a consultant, arrived at Ground Zero with 650 pounds of equipment to outfit search dogs looking for victims’ remains with wireless low-light video cameras and two-way radios and monitors for search and rescue K-9 handlers. Richard managed to assemble eight systems at the operating base next to Ground Zero. Mary Green (6612) joined him for three days, helping him assemble the collars and parts and coming up with several variations and improvements on the original camera collars.

Richard says he worked with search-and-rescue teams from all over the country who asked to buy the devices, but they were never commercialized. He says a company in California is interested in manufacturing them for such teams.

* * *

As a new week dawned, the calls for help from around the nation continued. Betty Biringer (5942) recalls Org. 6400 being “bombarded” with calls for their security risk methodology for federal dams, which had been completed that August. They started applying the methodology to other facilities, particularly for large metropolitan governments that called to say they had hundreds of critical structures they needed to protect.

“It was pretty sobering: the realization that it was no longer a technical problem or a paper exercise; it had really happened,” Betty says. “We’ve got to protect the nation from this. There was a feeling of nationalism among us. We all knew why we went to work every day.”

Sandians also helped outside the workplace. Bruce Berry (6833), who was then a Sandia emergency planner, Troy Hamby (4136-1), Lloyd Rantanen (3333), Mike Hessheimer (1534), and Gerald Wellman (1525) were on the New Mexico Urban Search and Rescue Task Force that traveled to the Pentagon to help recovery efforts. Working 18-hour days, they shored up damaged parts of the five-story structure, searching for survivors and recovering airplane parts along the way.

“You can’t help feeling anger or hate that this act was done. Of course, you can’t dwell on that because you are there to do a job. But you come across remains and you wonder, whose mother was this? Whose son?” Berry said at the time.

Across town, Roger and his teammates provided a classified briefing to Gordon on their findings.

“There were a number of important things that were done because of the report,” Roger says, explaining that he cannot provide details.

After the briefing, the team flew home. “For those of us who had spent these feverish five days in Washington it was such a relief to get home because it had been so intense,” Roger says.

A decade later, Roger remains proud about what he, Tom, Jim, and the others accomplished.

“The ability of this laboratory to contribute to this was a reflection of 30 years of capabilities and development of our understanding of how security and technology come together,” he says.

But his feelings are mixed when it comes to security actions taken since 9/11.

“9/11 was a wakeup call for the country and those of us at the Labs who had responsibilities in security to say that events that we had deemed relatively unlikely needed to be more seriously evaluated in terms of finding the balance of money and security,” Roger says. “As a nation we still haven’t adequately dealt with that.”

* * *

On Oct. 5, former Lab News editor Ken Frazier wrote in the newspaper that he hoped some semblance of normalcy was returning to Sandia.

“Nothing is quite the same. Nor ever will be. But there seems to be a little less tension than marked those first two horrible weeks after Sept. 11,” Ken wrote. “People are allowing themselves to emerge a bit from what, after all, has been an intense period of communal national mourning.”

* * *

Wes went on to serve multiple Army tours, eventually retiring as an active component colonel. These tours included serving as the senior antiterrorism/force protection officer for Iraq and later as base commander of Camp Ashraf, in Iraq, where he worked closely with an Iranian opposition group based there. During these tours he continually called on Sandia for help with certain security issues.

* * *

Paul, who retired from Sandia in February 2006, says, 9/11 “changed our thinking about being the Labs the nation turns to first for solutions to tough problems in science and technology. 9/11 was a small culmination of that. We were harvesting a lot of work people had been doing for several years.”

* * *

Several people, particularly those working in security at Sandia, say “normal” didn’t ever return.

“I think it forever changed the way we looked at physical security because it changed the threat spectrum, I don’t think it’s ever been the same,” Betty says.

* * *

After 9/11, Gary received calls from colleagues congratulating him on correctly stating that bin Laden was a threat before 9/11.

“I had this sense of professional pride, but I felt guilty that 9/11 had happened,” he says.

Over the next six months, Gary conducted as many as 60 briefings to NATO members about his work on terrorism, but he still wonders whether he could have done more. “Most people didn’t want to hear about such things,” he says. “All my life, I’ll wonder, should I have pushed my ideas more strongly? Could they have made a difference?”

This narrative of the days following 9/11 at Sandia was taken from previous issues of the Lab News and interviews with Paul Robinson, Roger Hagengruber, Jim Larson, Tom Bickel, Dennis Miyoshi, Wes Martin, Gary Richter, Betty Biringer, Richard Sparks, Mary Green, Iris Aboytes, and Randy Montoya.