Individuals responding to “dirty bomb” explosions during the first 48 hours can now rely on new protective guidance thanks, to researchers at Sandia and Brookhaven National Laboratory.

The research goal was to provide science-based response recommendations to the Department of Homeland Security for use in community preparedness activities. The research helps lessen health impacts to those who might be exposed to material from a dirty bomb, formally known as a radiological dispersal device (RDD).

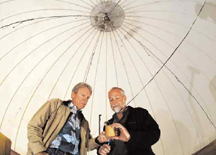

Featured in a cover article in the April issue of the journal Health Physics, the guidance is offered by Sandia senior scientist Fred Harper (6417) and Brookhaven National Laboratory health physicist Stephen Musolino.

The guidance shows that management of public health for the effects of an RDD is different from the approach taken for chemical or biological terrorism, and gives first-responders and planners science-based options for new response strategies.

While the particulate cloud from an RDD can be hazardous, it is not as immediately dangerous to life and health as anthrax or chemical agents. Until now, many planners were treating biological, chemical, and radiological agents identically, resulting in overly conservative and inefficient procedures for the first-responders.

More than 500 explosive experiments were conducted during some 20 years at Sandia to determine how the radioactive material in an RDD would disperse in the environment through aerosolization, the formation of a cloud of particles. The experiments were conducted in large sealed chambers for “dirty bomb” scenarios and performed on various materials including ceramics, metals, powders, and liquids. The materials used in the experiments helped determine the dispersal characteristics of most realistic radioactive sources that could be predicted accurately.

The quantities of material used to simulate the radioactive material, the shock physics, and the aerosol physics representative of what might occur in the detonation of an actual device were all tested. The results were then applied to predict the dispersal of actual radioactive sources using many different device designs.

“We focused on sophisticated aerosolization techniques to provide the responders with guidance based on what is realistically possible,” Fred says. “We’ve also performed experiments investigating some of the more probable aerosolization techniques that terrorists might employ.”

High zone established

Based on the experiments, the researchers recommended establishing a “high zone” with boundaries of 500 meters in all directions from the point of detonation. Because of the large number of experiments conducted for the study, Fred says, first-responders can follow it without radiation measurements if they know there is radiation associated with the explosion.

Responders are advised to evacuate this “high zone” and control access to prevent uncontaminated people from entering the affected area.

The guidance instructs first-responders in how to interpret radiation levels and assists them with decisions such as where to locate a command post, how to triage contaminated personnel who may need medical evaluations due to inhalation of radioactive material, and how to handle individuals who may not need an urgent medical exam for radiation injury.

The guidance also provides answers to complex questions such as whether to shelter-in-place or evacuate the public, because the timing of protective actions can affect the amount of radiation exposure.

“With this guidance first-responders can now have a tool to help them make the tough decisions they will be faced with in those first critical hours,” Fred says.

Musolino says the new strategies will help speed up lifesaving efforts to aid the injured victims and minimize the overall radiation dose to the public.

“I hope a terrorist act with an RDD never happens. But if it does, we want the first-responders to have the best science behind the tough decisions they will make in those first critical hours,” he says.

The research was funded primarily by DOE and the DOD’s Defense Threat Reduction Agency. Recently, the DHS and Nuclear Regulatory Commission contributed to the work, DHS coordinating the outreach effort with the first- responder community.