3.2.10. EDC Turbulent Combustion Model

The combustion submodel is Magnussen’s Eddy Dissipation Concept (EDC) and development details can be found in Magnussen, et al. [43], Magnussen [44], Byggsty{o}l and Magnussen [45], Magnussen [46], Lilleheie, et al. [47], and Gran and Magnussen [48].

3.2.10.1. Model Characteristics

The underlying assumption in the EDC model is that combustion in turbulent flows is controlled by turbulent mixing. The combustion model is an algebraic zone-type model and is influenced by local cell (control volume) values only. The model derivation assumes that the minimum cell dimension is large relative to the thickness of a flame (reaction zone) structure. This thickness varies with strain-rate, but the cell size should not be less than a few millimeters. The equations are not valid for laminar or near-laminar flow, but are based on fully developed turbulence arguments. The turbulent combustion model uses information from three sources: 1) thermochemistry, 2) species and state information from the cell values, and 3) turbulence kinetic energy and dissipation. From these data, the model creates source/sink terms for species equations and the energy equation (via radiative transport).

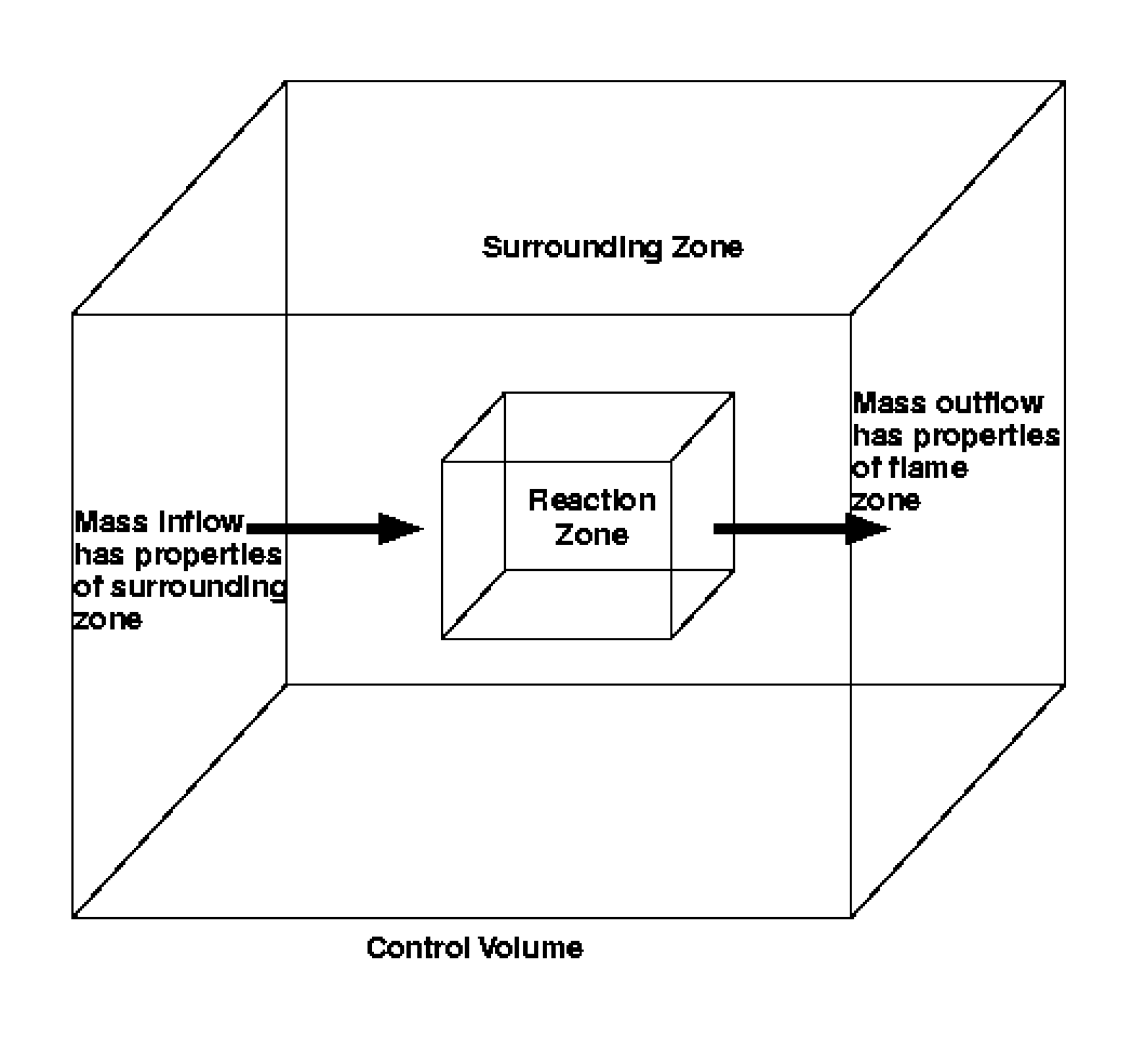

The model function is to provide an integral effect of combustion processes occurring within the control volume for the duration of a time-step. In this manner, reaction zone structures are not resolved, but the aggregate effect of turbulent combustion is modeled. To model the integral effect, two homogeneous zones are defined within each control volume for which there is combustion, as shown in Figure 3.3. The zones are termed the reaction zone (fine structures) and the surrounding zone. The size and mass exchange rate between these zones are influenced by the local turbulence properties and are the principal means by which turbulent fluctuations are accounted for within the model. The assumption that each zone is homogeneous is equivalent to assuming that the mixing within each zone is instantaneous. Since combustion occurs within (but is not limited to) the reaction zone, the assumptions for combustion correspond to those for a perfectly stirred reactor (PSR). Slower reactions can also occur in the surroundings, in which case, the assumptions for reaction in the surroundings are also consistent with PSR assumptions.

Fig. 3.3 Model geometry for Magnussen’s Eddy Dissipation Concept. The control volume is comprised of two zones; the properties of each zone are assumed to be adequately represented by a single set of values (i.e., lumped or perfectly stirred). The mass exchange between the zones is controlled by turbulent mixing.

3.2.10.2. Physical Interpretation

Magnussen’s EDC model is derived to be a general combustion model for premixed to non-premixed scalar fields and for high to moderate turbulence levels. It is not intended to be used for laminar combustion. Magnussen’s physical interpretation of combustion is based on the concept that chemical reaction occurs in regions of the flow in which the dissipation of turbulent energy takes place, i.e., fine structure regions. These regions are concentrated in isolated volumes and represent a small fraction of the flow. The regions have characteristic dimensions that are of the Kolmogorov length scale in one or two dimensions, but not the third.

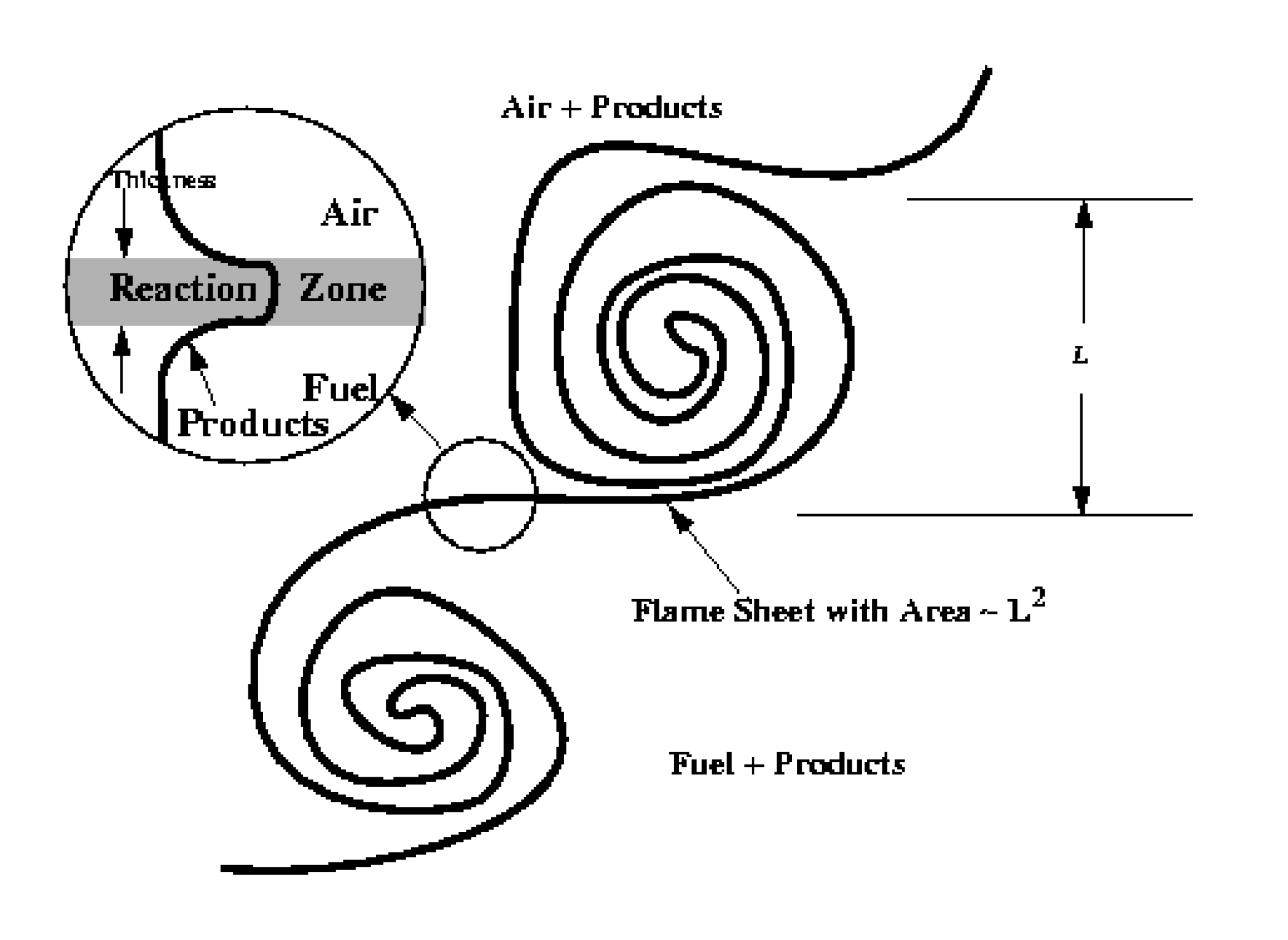

Fires are buoyant flows. Turbulent fires tend to be large, having base diameters above a meter. The turbulent length scales are large and the flow velocities are relatively slow, on the order of meters to tens of meters per second. (Still photographs of reaction zone structure within large fires can be found in Tieszen, et al. [49]). Therefore, turbulence levels tend to be moderate. Near the base of a fire, the combustion zone can be characterized as a continuous wrinkled flame sheet that appears to wrap around larger turbulent structures. The basic combustion mode is that of a strained diffusion flame with large surface area due to the turbulence. At higher elevations in the fire, turbulence levels increase and the character may change. Premixed combustion is possible as unburned products in the smoke are re-entrained into the fire. While Magnussen’s model was originally derived in terms of high turbulence levels resulting in fine structure regions (i.e., localized regions of high vorticity at dissipation scales), the model is appropriate for moderate turbulent intensities that occur in fires.

Figure 3.4 shows the physical geometry from which the combustion model will be derived for fires. Turbulence controls the reaction and surrounding volume fractions and fuel mass transport per unit volume. In general, turbulent momentum exchange processes result in scalar stirring at all length scales down to molecular mixing processes which are diffusion controlled. Without length scale information below the grid scale of the computation, it is impossible to correctly represent the interactions between all the relevant physical processes at their relevant length scales.

Fig. 3.4 Assumed flame surface geometry. is the integral turbulent length scale. The reaction zone thickness is characterized by the Kolmogorov dissipative turbulent length scale,

.

Magnussen’s EDC model attempts to represent the mixing processes that are most important to the overall heat release from combustion. It it based on the assumption that the overall heat release rate is controlled by the mass transport into the reaction zone. Therefore, considerable effort is made to model turbulent momentum processes that affect mass transport into the reaction zone. In the surrounding gases, turbulent mixing occurs with (in all likelihood) a similar vigor, however, its effect on the combustion rate is considered less important since the turbulence is not directly contributing to mass transport into the reaction zone. For this reason, there are two different levels of mixing assumptions made within the model.

With respect to Figure 3.3, the turbulence level in each control volume is taken into account in the consideration of the mass exchange between the reaction zone and the surrounding zone. However, within each zone, it is assumed that the properties are instantaneously homogeneous and uniform, i.e., perfectly stirred. This perfectly stirred assumption obviously over-predicts mixing within each zone for any real level of turbulence, and only begins to approximate reality at the highest levels of turbulence. On the other hand, the perfectly stirred assumption allows point calculations to be made in each zone for conveniently determining thermochemical properties. Without this assumption, it would be necessary to specify the gradients within each zone and integrate the specified gradients throughout the cell to obtain cell averaged property information. The approach here is to assume that over-predicting mixing within each zone via the perfectly stirred assumption has only a secondary effect on heat release rates within each cell.

3.2.10.3. Thermochemistry

Within the current strategy, chemical reaction can occur in both zones. However, in the simplest case, no reaction occurs within the surroundings due to the low temperature and unmixedness; all reaction occurs within the reaction zone. The notion of zones, perfect stirring within the zones, and type of chemistry involved are all independent assumptions, but have interrelated consequences. For example, finite-rate chemistry involving hundreds or thousands of species could be considered within the zones. From the perfectly stirred assumption within each zone, the finite-rate chemistry would be calculated as if it were occurring in a perfectly stirred reactor. In a real diffusion reaction, there are spatial variations in species concentrations for real turbulence levels so that the various chemical pathways, as well as heat, mass, and momentum transport, in a real strained diffusion flame can be quantitatively different than those calculated on the basis of perfect stirring. This effect is probably the strongest disadvantage of the perfectly stirred assumption. Only in the limit of infinitely-fast turbulent mixing does perfect stirring actually exist. In practice, the computation of detailed, finite-rate chemistry concurrently with a three-dimensional fluid mechanics calculation is expensive. Except in the limit where the turbulent strain rate is high enough that finite rate chemistry is warranted, it is adequate to use simpler descriptions of the chemistry. In the case of high strain rates, precalculation of the chemistry is usually done and the results tabulated in a look-up table to determine extinction limits.

For the current implementation, it is assumed that the chemistry can be represented as irreversible, “infinitely-fast” reactions that occur within each reactor. In classical combustion studies, the concept of “infinitely-fast” reactions is not usually invoked in the context of a perfectly stirred reactor. In the context of the current model, the meaning of an “infinitely-fast” reaction in the flame zone (a perfectly stirred reactor) is that the reactant stream entering the reaction zone is converted to products instantly as it enters the zone, and then the products are mixed instantly throughout the zone. The zone then reflects the thermodynamic properties of the combustion products at the adiabatic flame temperature for a given composition while the surrounding zone has the properties of reactants (and possibly previously combusted products) near the cell temperature.

In general, if the turbulent mass exchange rate between the zones (i.e. strain-rate) is sufficiently high that infinitely-fast chemistry assumptions do not apply, then finite-rate reactions within the perfectly stirred reactor can be used. Residence time scales that warrant finite-rate considerations tend to be at the sub-millisecond level. In the current implementation, the case of high turbulence levels leading to blow-out of a reactor is treated as a limits test. The test method is discussed in Limits Testing.

In principle, it is not necessary to assume irreversible chemistry within each zone. At long time scales (i.e., low turbulence levels), chemical equilibrium will result. The use of irreversible chemistry avoids the need to calculate the equilibrium state of the forward and reverse reactions for every combusting cell at every time step. For the current implementation, the time savings is deemed to be worth the cost in accuracy.

Regardless of the assumptions about chemistry employed in modeling the reaction zone, the actual reaction zones in a fire will very likely be similar to strained diffusion flames (wrinkled flame sheets wrapped into vortical structures). Perhaps higher in a fire with the re-entrainment of smoke, partially premixed combustion can occur. For diffusion reactions, combustion occurs within a region encompassing a stoichiometric surface between fuel and air. Therefore, the reaction zone is modeled as occurring with stoichiometric reactions. The reactants being transported into the reaction zone via turbulent mixing come from the surroundings zone and thus have the composition of the surroundings. There will be a limiting amount of one reactant if the combustion is to occur at off-stoichiometric conditions. The excess of the other reactant, prior products, and inerts do not participate in chemical reactions, but are transported in and out of the combustion zone by turbulent mixing. However, their presence affects the zone properties (for example, through their heat capacity).

Combustion products are transported into the surroundings

at the same rate as the reactants are transported into the

reaction zone (conservation of mass). However, the perfect stirring

assumption for properties means that these products have uniform

properties. In a diffusion reaction, products mix with fuel on

one side of the reaction zone and air on the other. On the fuel

side of the reaction zone, significant amounts of CO and soot

can result from interaction between the inflowing fuel and

outflowing products. The formation of CO is important not only from a

toxic pollutant perspective but its formation results in

significantly less heat release and lower temperatures.

Given the limits of a two-zone model with perfect mixing

within each zone, there is no simple way to model both

stoichiometric combustion and the formation of CO on the

fuel side of the reaction. In the current formulation, an ad-hoc

approach is used in which combustion in the reaction zone is

assumed to occur in sequential steps, each of which is irreversible

and infinitely fast. The first step is stoichiometric oxidation of

the fuel species

to CO and products. The second step is the oxidation of CO

and

to

and

provided

there is excess

in the reactant

stream. If the overall stoichiometry in the

control volume is fuel rich, significant amounts of

CO and

will be formed, while if it is lean

only

and

will be formed.

3.2.10.4. Chemical Mechanism

For an arbitrary CHNO fuel, the stoichiometric, irreversible

reaction to CO and products is given by

(3.237)

where ,

,

, and

are the numbers of carbon, hydrogen,

nitrogen, and oxygen atoms within the fuel molecule, respectively,

and the terms in parentheses are the stoichiometric coefficients.

The summation term for diluents includes all other species present in the reaction stream including nitrogen in air, combustion products in the surroundings from previous combustion processes, etc… Diluents, including the combustion products, are assumed to have no effect on the chemical reaction itself. However, diluents do have an effect on the temperature rise through their specific heats and the presence of products is used as an ignition criteria for the combustion model.

The assumption that combustion products act like diluents (i.e.,

have no effect on the reaction) is obviously a simplification.

Product species include CO, ,

,

and

. The presence of CO and

in the reactant stream would affect equilibrium results;

however, irreversible reactions have already been assumed in the

model so the presence of these species does not represent an

additional simplification. On the other hand, the presence of

large amounts of

and

in the reactant stream may reduce the amount of

consumed for a given amount of fuel due to partial

oxidation of the products via the oxygen in the

and

in an overall fuel rich environment.

However, this effect is partially compensated since the

extra

would be consumed by the second reaction.

The second reaction is the subsequent oxidation of CO and

to

and

.

This reaction oxidizes both the CO and

produced by the first reaction and any CO

and

that passed

through the first reaction as products (i.e., diluent). The

reaction is given by

(3.238)

In the current implementation, soot is considered to be a trace species. As such, its mass and energetics are not considered part of the above chemical reactions. Soot has its own production terms and is considered to oxidize in proportion to the fuel oxidation in the first reaction. See the soot model in Soot Generation Model for Multicomponent Combustion for details.

3.2.10.5. Species Consumption/Production Limits

The reactants being transported into the

reaction zone come from the surroundings and therefore have

the same composition as the surroundings. As such, the reaction

can only proceed within the limits of available fuel and oxygen

from the reactant stream.

For example, if there is insufficient oxygen in the reactant

stream, then all of the oxygen will be consumed by Reaction 1,

((3.237)),

and the excess fuel will be passed with products from Reaction 1 to

Reaction 2, ((3.238)). Reaction 2 will not take place

because all the oxygen

was consumed in Reaction 1 (i.e., in both reactions, oxygen is

limiting). If there is insufficient fuel in Reaction 1, then all

the fuel will be consumed and excess oxygen will be passed

to Reaction 2. Depending on the ratio of oxygen to CO and ,

all the secondary fuels may be consumed or all the oxygen may be consumed.

To find the limiting mass, it is convenient to define an equivalence ratio. Equivalence ratios are normally defined in terms of molar ratios, but mass ratios yield the same result [50] and are preferred here since mass fractions are used in the transport equations.

(3.239)

The numerator is the ratio of the actual mass of fuel to oxygen in the reactant stream,

(3.240)

The denominator is determined for each reaction. Generically, the first and second reactions have the following form

(3.241)

where are stoichiometric coefficients on a molar basis.

The stoichiometric fuel to oxygen mass ratio is

(3.242)

where is a molecular weight.

Specifically for the first reaction, the stoichiometric mass

ratio of

to

is

(3.243)

Therefore, the equivalence ratio for the first reaction which is based on carbon monoxide and hydrogen products is given by

(3.244)

and similarly, the equivalence ratio for the second reaction which is based on carbon dioxide and water products is given by

(3.245)

If either equivalence ratio is greater than unity, then the

mass of oxygen will be completely consumed by its reaction.

If either equivalence ratio is less than unity, then the mass of

fuel will be completely consumed by its reaction. If either

equivalence ratio is unity, then the mass of fuel and oxygen

will both be completely consumed by that reaction. Note that

is not a fuel in the

second reaction because if there

is any of this fuel left, all the oxygen was consumed in the

first reaction. Therefore, under these conditions the second

reaction cannot proceed due to lack of oxygen. Also note that

the expression for

does not identify which secondary fuel,

CO or

, is limiting.

In order to determine the limiting reactant mass in a multi-fuel

(or multi-oxidant) system, a more general approach based on

equivalence ratios is required. Consider the reaction

where

are stoichiometric coefficients. The stoichiometric

mass ratio of reactant

to

is

(3.246)

Further, and

are the mass fractions of

and

in the mixture and

(3.247)

The ratio of these quantities is an equivalence ratio; i.e., if

(3.248)

then is the limiting reactant, else

is the limiting reactant.

However, this inequality can be usefully rearranged. If

(3.249)

then is the limiting reactant. The same procedure can be shown

to apply to reactions where there are more than

two reactants; i.e., if

(3.250)

then is the limiting reactant of

reactants. Therefore,

(3.251)

Note that the units of are

[

]/

.

Also note that

diluents are not reactants and they are not depleted by the reaction.

The

function should only be applied to fuels and oxygen,

not to all species.

To determine the change in mass fraction, ,

of reactant species

due to reaction

, multiply the

limiting mass expression by the stoichiometric mass of species

:

(3.252)

This expression has units

of []

[

].

Since

is the limiting reactant, the expression within the second

set of square brackets is the change in mass

fraction of species

due to reaction

; this is because the

limiting species

is completely used up in the

reaction (i.e., the mass fraction of species

goes to zero).

The expression within the first set of square brackets modifies

the change in mass fraction of species

to yield the change in mass

fraction of species

due to reaction

. The change in mass fraction

of product species

in reaction

is similar but without the

minus sign in the above expression.

Since the reactions are given priority, the “products” of Reaction 1 are the “reactants” of Reaction 2. The new mass fractions in the reactant stream for Reaction 2 are given by

(3.253)

As noted above, the sign of the second term,

, is positive

for products and negative for reactants.

Similarly, the product composition from Reaction 2 is given by

(3.254)

Here again the positive sign on the second term is used for products and negative sign is used for reactants. Since the reactions are assumed to occur infinitely fast, the product composition for Reaction 2 is the composition of the reaction zone,

(3.255)

3.2.10.6. Conservation Laws

For convenience we restate the Favre-averaged species mass conservation equation, (3.106),

(3.256)

where is the time averaged density

of the mixture,

is the Favre-averaged mass fraction

of species

,

is the Favre-averaged

velocity of the mixture,

is the turbulent eddy

viscosity,

is the turbulent Schmidt number,

and

is the time-averaged mass

production rate of species

per unit volume of the mixture.

This equation is solved on a mesh, one control volume of

which is shown in Figure 3.3. Within the control volume,

the species

mass consumption/production rate,

,

is determined by the EDC model, assuming that the mass transfer process

into and out of the reaction zone from the surroundings

(cf. Figure 3.3) can be represented as a steady process,

(3.257)

The mixture mass flow rate between the surroundings and the reaction zone is also assumed to be steady,

(3.258)

Combining these two expressions yields

(3.259)

It is convenient to normalize this equation with the mass of the control volume, or

(3.260)

The term in the brackets is a function of thermochemistry only and is specified by the chemical processes derived in the previous section. The second term, the normalized mass transfer rate, is a function of the turbulent mass exchange rate between the reaction zone and its surroundings. The derivation of this term is the subject of the next subsection.

3.2.10.7. Effect Of Turbulence On Combustion Rates

Magnussen derived the effect of turbulence on combustion rates in terms of high turbulence levels. The derivation here will be for moderate turbulence levels for the flame geometry shown in Figure 3.4. The derivation herein does not include proportionality constants. Rather, dimensional reasoning is used to establish the relationship between reaction zone surface area, volume, and mass transfer rates with respect to the prevailing turbulence levels. Constants of proportionality, taken from Magnussen’s original derivation, are added at the end.

Characteristic scales are needed for the mass transfer velocity into the reaction zone, the reaction zone surface area, and the reaction zone thickness. The mass transfer velocity into the reaction zone is a velocity appropriate to diffusional length scales that are being modified by the local strain field induced by the turbulent flow,

(3.261)

An appropriate diffusional velocity is the Kolmogorov

velocity, , which is characteristic of

dissipative length scales (i.e., those in which the

local strain field is being dissipated by

diffusional effects). From Kolmogorov’s definition,

is given by

(3.262)

where is the molecular mixture kinematic viscosity

(evaluated at the surrounding temperature),

and

is the rate of kinetic energy dissipation.

The reaction zone is characterized as a continuous flame sheet, highly wrinkled and wrapped around large eddies. The volume of a large eddy is characterized by

(3.263)

where is the characteristic integral length scale of the turbulence.

The reaction zone area is assumed to be proportional to

both momentum and scalar influences. While all length scales

of the turbulent cascade contribute to wrinkling and stretching

the flame, it is assumed that large changes in surface area are

associated with large length-scale fluctuations. Therefore, it is

assumed that the square of the integral length scale is the most

appropriate turbulent length scale for characterizing the reaction

zone area.

Species concentrations also affect reaction zone area. Obviously,

if no fuel is present, no reaction zone will be present

regardless of level of turbulence present. The species influence

are denoted by a function, , the rationale of which will be

described later. Based on these arguments,

(3.264)

To obtain property values for each zone in Figure 3.3, it is

necessary to define the volume fractions of the reaction zone

and surrounding zones. The reaction zone volume fraction is based

on a reaction zone area and a reaction zone thickness. Since the

reaction zone is a strain modified diffusional zone, its thickness

is best modeled with a diffusional length scale that is characteristic

of the turbulence-induced strain field. Thus the reaction zone

thickness is proportional to the Kolmogorov scale, ,

(3.265)

Kolmogorov’s definition of the diffusive length scale is

(3.266)

Since this is a characteristic scale analysis, the molecular mixture viscosity is evaluated at the surrounding temperature. The actual reaction zone thickness will be larger due to the volumetric expansion (i.e., lower density) in the reaction zone.

Based on these characteristic scales from the assumed reaction zone geometry in Figure 3.4, expressions can be obtained for the mass transfer rate per total mass. The mass exchange rate into the reaction zone per unit eddy mass is given by

(3.267)

The first term on the right hand side is given by

(3.268)

The interpretation of the second term on the right hand side depends upon filtering used (i.e., averaging over scales). For LES, the length scale of the eddy being modeled is proportional to the length scale of the grid. In this case, the size of the eddy and the grid are the same. Therefore, the second term is unity. In RANS modeling, the eddy is much larger than the grid, as is the reaction zone surface being modeled. For RANS, it is assumed that averaged over a sufficient number of eddies, the mass exchange rate into the reaction zone per unit eddy (first term) is uniformly distributed (i.e., independent of length scale) up to the integral length scales. In this case the second term is irrelevant and is assigned a value of unity. For example, for an integral scale eddy with a length scale ten times the grid, the mass transfer into the reaction zone (averaged over many eddies) would be ten times the value for an eddy with a length scale that is just the size of the grid.

Conservation of mass requires that the mass exchange rate into and out of the reaction zone be identical so the properties can be evaluated at the thermodynamic state of either the reactant stream (surroundings) or the product stream (reaction zone). For convenience, they will be defined in terms of the reactant stream temperature and mass fractions. Using the characteristic length and velocity scale arguments given above yields

(3.269)

The standard integral scale estimate [10] of the rate of energy supply to diffusive scale eddies is

(3.270)

The turbulence kinetic energy is given as

(3.271)

Substituting and rearranging gives

(3.272)

Ignoring the constant of proportionality and substituting the results into the definition for the Kolmogorov velocity gives

(3.273)

Substituting gives the mass exchange rate into the reaction zone per control volume in terms of standard turbulence parameters,

(3.274)

The function is a scalar correction to take into

account species effects on the reaction zone area.

The function is bounded between (0,1) with 1 representing

optimal species concentrations which

will maximize the reaction zone area and 0 representing

prohibitive species concentrations which

would prevent reaction zone formation. Two scalar

properties are important, the reactant

concentrations and the product concentration

(which acts as an ignition source since ignition is

not assumed). Therefore, the limiter is written as

the product of two terms,

(3.275)

The function is intended to take into account

the effect of the reactant mass fractions on the

reaction zone surface area.

Since the reaction zone surface occurs at

stoichiometric concentrations of fuel and oxygen in a

diffusion flame, stoichiometric

concentrations of reactants in a control volume

will result in the largest reaction zone area

(controlled by the turbulence levels). In this

case,

is unity. On the other hand, if either fuel or

oxygen is zero within a control volume, then

is zero.

Between these extremes, a functional form is assumed

which has the correct limiting properties.

The function is given by

(3.276)

where the normalized mass fractions are defined below.

Overall reaction stoichiometry is determined from the sum of Reactions 1 and 2 in the chemical reaction section ((3.237) and (3.238)). The overall reaction is

(3.277)

For the overall reaction, the mass ratio of oxygen to

the mass ratio of fuel for stoichiometric

reaction to and

is given by

(3.278)

Since mass is conserved in the reaction, kilograms

of product (

and

) are produced

for every kilogram of fuel consumed for a fuel/oxygen

reaction. Note the mass of diluents, such as

the nitrogen in the air does not change, as a

result of the reaction. It is useful to produce

normalized mass fractions based on the masses involved

in the stoichiometric reaction.

(3.279)

Note that the sum of these terms does not equal unity but one minus the mass fraction of diluent in the mixture.

The actual reaction may involve the secondary fuels, so a more general expression is required for the stoichiometric mass ratio of oxygen to fuel (and is used in the Vulcan code).

(3.280)

(3.281)

(3.282)

(3.283)

The product mass fractions are adjusted for the mass of nitrogen that accompanies the oxygen in air – the nitrogen is treated as a product species. The normalized mass fractions are

(3.284)

where

(3.285)

The molar ratio of nitrogen to oxygen in air is 3.76 and the mass

ratio is 3.29. The production mass fraction, , can be

computed directly from the

and

mass fractions as long as the only source of product species

in the flow field comes directly from combustion. If there is

injection of product species into the domain from a diluent stream

or from an ambient concentration, then a transport equation should

be solved for the product mass fraction (see Combustion Products Transport Equation).

Since combustion always occurs at a stoichiometric surface in a diffusion flame, there is a limiting reactant mass fraction in a fuel/oxygen mixture within the control volume unless the ratio is stoichiometric. The limiting reactant mass fraction is given by

(3.286)

The function can be seen to approach the correct

limits most clearly if the mass fraction of

products,

, is set to zero. If the mixture is

fuel lean,

and

is equal to the fuel to oxygen ratio which decreases to

zero as the fuel

mass fraction is decreased. If the mixture is

fuel rich,

and

is

equal to the oxygen to fuel ratio which decreases to zero

as the fuel mass fraction is increased. At stoichiometric,

is unity.

The function is intended to take into account the

existence of reaction zone surface as a

precondition for reaction zone surface propagation.

A stoichiometric surface without reaction can

exist in a flow field if there is no ignition source.

An external source is required for ignition.

However, once ignited, reaction zone propagation can

be interpreted as new flame surface being

ignited by existing adjacent reaction zone surface.

A good indicator of existing flame surface is

the presence of hot combustion products within the

control volume and this fact is used to

create the function

.

The value of is zero if no combustion products are present.

If the product mass fraction was uniformly distributed,

then the probability of ignition would

increase with the ratio of product mass fraction

to reactant mass fraction. However, the

combustion products are not uniformly distributed

but concentrated around the reaction zones,

thereby increasing the probability of propagation

of reaction zone surface for a given product

mass fraction. The assumed functional form of

that has these characteristics is

(3.287)

(3.288)

The maximum volume of the reaction zone is the thickness times its area,

(3.289)

Using the definition for the Kolmogorov length scale

and substituting the turbulence kinetic

energy for length scale, , gives

(3.290)

which is the maximum reaction zone volume per eddy volume.

The value of is bounded by one since the

length scale ratio of the flame volume to eddy volume cannot

be larger than one.

The characteristic product volume can be defined by assuming the majority of combustion products are held up within a distance corresponding to the Taylor microscale from the reaction zone surface,

(3.291)

Note that this assumption is used only to establish an ignition probability. For actual property evaluation, it is assumed that the combustion products are well mixed with the surroundings. Taking the ratio of the volumes gives,

(3.292)

Using the standard definition of this ratio (Tennekes and Lumley [10]) gives,

(3.293)

The Reynolds number can be defined in terms of turbulent kinetic energy and its dissipation by,

(3.294)

Substituting gives,

(3.295)

The existing product mass fraction is given by .

The maximum possible product mass fraction is the sum

of the existing products and the products that could be

formed if all available reactants were to burn. Since

combustion takes place at a stoichiometric surface,

the limiting reactant mass fraction is given by

.

Therefore,

becomes

(3.296)

Functionally, can exceed unity but the product

is limited to the range (0,1). The function

is now

completely described in terms of species and turbulence

properties.

Combining all previous results gives the following result for species consumption/production,

(3.297)

where is defined above in terms of

,

.

The above derivation is intended to provide a physical interpretation to Magnussen’s EDC model for large fires typified by medium turbulence levels with diffusive combustion. Proportionality constants are needed to close the model. As always, constants can be tweaked for a given flow to produce the best result for that flow. However, we will use the constants as derived for more general flows (Ertesv{aa}g and Magnussen [51]). With these constants, the model equations match those from the KAMELEON-II-FIRE code (Holen et al. [52]).

Using these constants, the maximum reaction zone volume fraction is given by

(3.298)

Taking into account species limitations, the flame volume fraction is given by

(3.299)

The reaction rate of fuel is given by

(3.300)

The additional scalar function, , at the end of

(3.300) is multiplier on the combustion rate that

Magnussen found necessary to maintain the mass transfer rate when the

product concentration is high in premixed flames. Its necessity suggests

that perhaps alternate scalings should be examined, but for consistency with

the published model, it is implemented here as

(3.301)

3.2.10.8. Average Control Volume Properties

The volume and mass exchange process between the two zones is assumed to be constant over a time step. Consequently, cell averaged properties for the mean flow equations are a volume weighted sum of the properties in the two zones. Therefore, all control volume properties are given by

(3.302)

The maximum volume fraction of the reaction zone, ,

was determined previously from momentum considerations.

The actual volume fraction is the maximum volume fraction

times the scalar function,

. The surroundings is the

volume fraction that remains after the reaction zone

volume has been removed. Therefore,

(3.303)

Volume averaged properties given by (3.303) are desired.

However, the

estimates used to obtain (i.e., (3.298))

are based on uniform cell temperatures. Clearly, the flame zone will

be hotter than the

surroundings, so the volume fraction occupied by the flame will be larger

than given by (3.303) (and the surroundings fraction

smaller).

A first order non-isothermal estimate is made to account for flame volume

fraction. This estimate assumes that the non-homogeneous density field

does not affect the local turbulence field (or alternately, that dilatation

cancels the baroclinic generation) such that isothermal, isotropic,

homogeneous turbulence estimates for the turbulent kinetic energy, ,

and its dissipation,

, hold. (This assumption is made in

virtually all models by the necessity that the fundamental research

to quantify the actual coupling has not been done.)

A mass balance then gives a first order estimate for the actual flame volume fraction at the flame temperature. The actual flame volume at the flame temperature is given by its isothermal estimate times the cell mean density (used to obtain the isothermal estimate) divided by the actual flame density.

Thus, (3.303) becomes,

(3.304)

Where the mean density is given by

(3.305)

An interpretation of (3.304) and (3.305)

is that , is intended as a non-isothermal volume estimate,

which the mass weighted isothermal volume estimate happens to be the best

available estimator until turbulence coupling in reacting flows can be

elucidated. All cell averaged properties are given by

(3.305). (3.303) is intended for

clarification only.

3.2.10.9. Limits Testing

Parameters in the EDC model take on limiting values in the presence of piloting conditions and extinction conditions. The limits are discussing in the following subsections.

3.2.10.9.1. Ignition Criteria

Ignition will not occur in the above mechanism unless products

are formed. An external ignition

source (or pilot flame) is simulated by setting to be greater

than zero (the product mass fraction is set to 0.2 times the

maximum products that could be formed by the existing fuel in the current

implementation) in a cell with fuel and oxygen present. This can

be done on a cell by cell basis to

represent point ignition sources, or in the whole domain if

global ignition is required. If a pilot

flame is to be simulated, the cells associated with it

have

set to be greater than zero for the

duration of the calculation. If a transient ignition

(e.g., spark) is to be simulated, the cells initially

have

set to be greater than zero. However, after a minimum

temperature is reached within a cell,

(K) (a user input),

is no longer specified but calculated

from the species concentrations and

turbulence levels as derived previously.

3.2.10.9.2. Extinction Criteria

Extinction occurs when . This occurs automatically when the

fuel and/or air is consumed. Local extinction can also be

caused within a cell due to high turbulence levels. At high

turbulence levels, the reaction zone can be appropriately

modeled as a perfectly stirred reactor (PSR). A PSR blows

out when the residence time is less than a minimum value

for a given composition. The residence time,

, in the

reaction zone volume is given by

(3.306)

Simplifying gives

(3.307)

Substituting prior relations gives

(3.308)

Simplifying and substituting Magnussen’s constant of proportionality gives

(3.309)

Comparison of the calculated residence time with a user

input minimum residence time (based on pre-calculation

using a PSR and appropriate chemistry) determines whether

or not combustion is allowed to continue. If so, heat

release is calculated as derived herein, and finite-rate

effects are not considered. However, if the calculated

residence time is below the minimum value, is set

equal to zero which causes combustion to cease within a cell.

3.2.10.9.3. Laminar Values

As currently formulated, the model assumes the flow is

fully turbulent and does not model laminar combustion.

Minimum values for the reaction zone volume, , and mass

transport into the reaction zone per mass in the

cell,

, are required in

conditions with low turbulence levels to prevent singularities.

3.2.10.9.4. Scalar Limits

The mass fractions of fuel, air, and products must remain bounded (0,1). This requires that the consumption rate for the species with the limiting concentration times the time step must be less than or equal to the mass of species.

3.2.10.10. Cell Value Information Used By Model

The combustion model requires inputs from the transport

equations for cell averaged variables at the start of a time

step. These variables include pressure, (dynes/

),

species mass fractions

, density,

(g/

),

mixture molecular weight,

, (g/mole), turbulent kinetic

energy,

(

/

), dissipation of the turbulent kinetic

energy,

(

/

), mixture kinematic

viscosity,

(

/sec),

individual (i.e., chemical plus sensible) enthalpies,

(ergs/g), and mixture enthalpy,

(ergs/g).

3.2.10.11. Model Outputs

The two outputs of the combustion model are the species consumption rates and property estimates.

3.2.10.11.1. Species Consumption Estimates

Noting the general relation between cell averaged values and surrounding values, (3.303), the surrounding and cell mass fractions can be related to give

(3.310)

Substituting this result and the definition of into

the species consumption/production rate

gives the source term in the species transport equation,

(3.256),

(3.311)

for the species mass production/consumption rate in a

control volume. The subscript is understood to be

for each species,

,

,

, CO,

,

,

, and

any diluents in the system.

3.2.10.11.2. Property Estimates

It is important in turbulent processes that nonlinear fluctuating quantities be appropriately represented. Properties for which nonlinear fluctuations are important include the radiative emissive power (proportional to the fourth power of temperature) and density.

To get the radiative emissive power, it is first necessary to get the temperature within each zone. This is accomplished by iterative estimate based on the species mass fractions within each zone. Since total (chemical plus sensible) enthalpy is used for each species, the total enthalpy per unit mass in the control volume does not change between the reaction zone or the surrounding zone. The partitioning of chemical and sensible enthalpy is different for the reaction and surrounding zone, but the specific total enthalpy is equal to the cell value defined at the beginning of each time step. (Note: this is not a statement of the energy equation, it is only a statement of property values within each zone and the cell. Obviously, the enthalpy does vary after radiation transport is allowed to occur and species are allowed to advect between cells at the end of the time step as governed by the energy equation).

The reaction zone temperature, , is obtained

from iterative solution of

(3.312)

and the surrounding temperature, , is

obtained from iterative solution of

(3.313)

The average emissive power is given by

(3.314)

An important assumption implied by the form of

(3.314) is that the turbulent fluctuations

between the temperature

and absorption coefficient are weakly correlated [7].

( Note that the intent of the averaging form above is to volume-weight

the emissive power from the flame and surrounding zones. This

form implies that should be viewed as a mass

fraction rather than a volume fraction as discussed for

(3.302). )

The density of each zone can be calculated according to the perfect gas law. For the reaction zone volume, the density is

(3.315)

where is the universal gas constant and

is

the constant thermodynamic pressure.

For the surroundings, the density is

(3.316)

The soot model uses the temperatures, densities, and mass fractions of reaction zone and surroundings according to the above estimates.

3.2.10.12. Combustion Products Transport Equation

The product mass fraction represents the products formed by combustion

( and

for hydrocarbon fuels, and

for hydrogen fuel). If any of the product species are injected into the

domain through either an initial condition or boundary condition to

simulate a diluent stream or ambient concentration, their

influence must be removed in order for the

reaction limiter to

function properly. A transport equation similar to

(3.256) is used where the reaction rate is given by

(3.317)

This transported product mass fraction can only be formed due to reaction within the domain and cannot be injected through either initial or boundary conditions. Therefore, the only boundary conditions that are required are at an outflow so that products may exit the domain, and a zero value at any surfaces where a species Dirichlet condition is applied. All of these cases are handled automatically so that nothing needs to be specified by the user.

Note that a pilot stream will be unable to ignite a flame when using this model. It will be treated as an inert diluent stream, so that the normal ignition model will be required to ignite the flame. This model in its current form should not be used for piloted flames.

Also note that if the only source of products in the simulation is combustion, then the product mass fraction can be computed directly from the local species mass fractions and solving this transport equation is unnecessary.

3.2.10.13. Chemical Equilibrium Models

The EDC combustion model uses a two-step chemical reaction, where the fuel

species is consumed by the reaction in (3.237) to form

and

, and then these intermediate species are

consumed by the reaction in (3.238) to form

and

. If oxygen is present in excess, then none of the

intermediate species will remain and only

and

will be produced. In reality, these reactions would not proceed to completion,

but instead would reach an equilibrium where some of the intermediate species

can persist. This can lead to a significantly different mixture composition

and even a different mixture temperature than what the standard EDC model

would predict, especially at higher temperatures.

Fuego includes two optional models that can include the effects of two independent chemical equilibrium reactions into the standard EDC model, to better predict high-temperature combustion species and temperatures.

3.2.10.13.1.  Dissociation Model

Dissociation Model

At high temperatures, the equilibrium reaction

(3.318)

becomes active to dissociate species back into

and

, which has the effect to cool the gas mixture. Including the

effects of this dissociation reaction will help to control nonphysically-high

temperatures that might result otherwise.

This model will adjust the EDC-reacted mixture in

(3.311) to include the effects of equilibrium

reaction (3.318). This equilibrium can be modeled by

(3.319)

where is the ideal gas constant,

is the temperature at which the equilibrium

is being calculated,

is the equilibrium constant for this dissociation

reaction, and

is the standard-state Gibbs function change for this

reaction. The equilibrium constant

for (3.318) is

defined as

(3.320)

where ,

, and

are the partial

pressures of

,

, and

, respectively, and

is the reference pressure taken as

. The standard-state Gibbs function

change for this reaction can be evaluated in terms of the Gibbs function of

formation for each species at temperature

,

(3.321)

The partial pressure of species can be computed by

, where

is the static pressure of the mixture and

is the mole fraction

of species

, defined as

with the total number

of moles of all species being defined as

.

After making these substitutions and simplifying, the equilibrium equation that

needs to be solved, written in terms of moles of each species in a fixed-mass volume,

is

(3.322)

Additional equations may be written to enforce conservation of and

atoms within the reaction volume,

(3.323)

(3.324)

where and

are the fixed number of moles of carbon and oxygen atoms,

respectively, during the equilibrium reaction. (3.322),

(3.323), and (3.324) represent a system of

three equations that can be solved for the three unknowns

,

, and

at the equilibrium state.

The numerical solution procedure begins by approximating the number of moles

of each species from the reacted mixture mass fraction vector as

, on a per-unit-mass-of-mixture basis. Eliminating

and

from (3.322) yields a nonlinear equation

that can be solved directly for

from the fixed atom balances at a fixed

temperature

and pressure

,

(3.325)

where represents the summation of the

number of moles of all species present in the mixture that do not participate

directly in the equilibrium reaction, {it i.e.} all species except for

,

, and

.

A standard Newton’s method may be used to iteratively solve (3.325),

(3.326)

where the function is (3.325) and the

derivative function

is

(3.327)

Once this equation is solved for , then the following equations

may be used to evaluate the remaining equilibrium species moles,

(3.328)

(3.329)

With the new molar mixture defined for the equilibrium species, the mass

fraction vector may be reconstructed by . This new mixture

composition will result in a different temperature since the enthalpy

is fixed. After the new temperature is evaluated, this entire procedure

may be repeated iteratively until the mixture temperature converges to within

a specified tolerance.

3.2.10.13.2.  Dissociation Model

Dissociation Model

Similar to the dissociation model described in

\mathrm{CO_2} Dissociation Model, at high temperatures the equilibrium reaction

(3.330)

becomes active to dissociate species into

atoms,

which has the effect to cool the gas mixture. Including the effects of this

dissociation reaction in addition to the

dissociation reaction

will help to control nonphysically-high temperatures that might result otherwise.

This model will adjust the EDC-reacted mixture in

(3.311) to include the effects of equilibrium

reaction (3.330). This equilibrium can be modeled by

(3.319), with the equilibrium constant defined as

(3.331)

where and

are the partial pressures of

and

, respectively. The standard-state Gibbs function

change for this reaction can be evaluated in terms of the Gibbs function of

formation for each species at temperature

,

(3.332)

Simplifying this equilibrium expression and writing it in terms of the number of moles of each species in a fixed-mass volume results in the equilibrium equation

(3.333)

An additional equation may be written to enforce conservation of atoms

within the reaction volume,

(3.334)

where is the fixed number of moles of hydrogen atoms during the equilibrium

reaction. (3.333) and (3.334) represent

a system of two equations that can be solved for the two unknowns

and

at the equilibrium state.

Similar to the dissociation model, the numerical solution procedure

begins by approximating the number of moles of each species from the reacted mixture

mass fraction vector

as

, on a per-unit-mass-of-mixture basis.

Eliminating

from (3.333) yields a nonlinear

equation that can be solved directly for

from the fixed atom balance

at a fixed temperature

and pressure

,

(3.335)

where represents the summation of the

number of moles of all species present in the mixture that do not participate

directly in the equilibrium reaction, {it i.e.} all species except for

and

.

A standard Newton’s method may be used to iteratively solve (3.335),

(3.336)

where the function is (3.335) and the

derivative function

is

(3.337)

Once this equation is solved for , then the following equations

may be used to evaluate the remaining equilibrium species moles,

(3.338)

With the new molar mixture defined for the equilibrium species, the mass

fraction vector may be reconstructed by . This new mixture

composition will result in a different temperature since the enthalpy

is fixed. After the new temperature is evaluated, this entire procedure

may be repeated iteratively until the mixture temperature converges to within

a specified tolerance.