25 years of Laboratory Directed Research and Development

Research at a national laboratory is concrete. It produces scientific and engineering solutions to real-world challenges tied to precise, vital missions. Most of the time.

Someone, somewhere, decades ago looked at the extraordinary talent and brainpower collected at the Labs and thought, what if?

What if the country turned those super-smart people loose to really explore what they could only imagine. Give them time and money to take science to the frontiers of possibility.

Thus was born Laboratory Directed Research & Development (LDRD), established in 1990 by Congress to let scientists at national laboratories do creative, innovative, independent research. “LDRD has allowed us to stay at the cutting edge of science in our core mission areas,” says Andy McIlroy, deputy chief technology officer and director of Sandia’s Research Strategy and Partnerships Center 1900. “The origin was the realization that national labs, particularly national security labs as opposed to science labs, needed to have a small portion of their budgets directed to forward-looking research.”

At Sandia, LDRD is funded as a percentage of all the programs that come into the Labs. Currently at just under 6 percent, or $155 million a year, it is directed toward long-term research that ultimately benefits the national security mission but may be at a lower technological readiness level than core programs can support. “It keeps the technical base fresh and forward-looking in ways the core programs might not be able to in the course of usual business, but is of long-term benefit to them,” Andy says.

Investment has paid off

The investment has paid off in 25 years with important scientific advances. LDRD funds much of the work in Sandia’s seven research foundations, each focused on a specific scientific discipline and overseen by the Office of the Chief Technology Officer. “Research helps us to envision things that haven’t been realized yet,” says Rob Leland, Sandia VP of Science & Technology and Chief Technology Officer. “We can look broadly across the scientific and engineering community and ask what new and emerging areas of research could have a beneficial impact on the nation, and then develop understanding necessary to bring them to life.”

The seven foundations are Bioscience, Computing and Information Science, Engineering Science, Geoscience, Materials Science, Nanodevices and Microsystems, and Radiation Effects and High Energy Density Science. “The foundations enable the mission and advance the frontiers of knowledge in science and engineering,” Rob says.

Research supports national security in important ways, Andy says. “We can look into new and emerging areas that, if mastered by an adversary, could be used to the disadvantage of us and our allies,” he says. “We can position ourselves to counter a threat if it becomes a reality.”

Attract and keep exceptional scientists

LDRD also has helped Sandia attract and keep exceptional scientists. “It offers the freedom to propose and explore your own, mission-relevant ideas and push the state of the art in new ways,” Andy says. “When you add in the national security mission, it is very attractive. We attract professionals who are among the smartest people on the planet, who are not afraid of challenging problems, and who believe national service is worthy of a career commitment.”

The LDRD process starts with a set of calls from research and mission foundations. Broad areas are identified that have the potential for strong mission impact in the short or long term. Researchers respond with brief proposals that are reviewed by experts within the Laboratory. About a fourth are asked to submit a full proposal. Those get an extensive programmatic and technical review. Roughly half will be funded.

“We get a lot of ideas,” Andy says. “There is quite a bit of scrutiny.” A typical LDRD project is funded at $200,000 to $600,000 and takes up about a third of the principal investigator’s time for up to three years. Typically, researchers work on other projects in addition to an LDRD project.

About 20 percent of Sandia’s LDRD portfolio is connected to Research Challenges, long-term, cross-disciplinary projects in 11 designated areas related to national security. “We’re looking for big, bold ideas to move the Research Challenges forward,” Andy says.

Groundbreaking discoveries and innovations

Not all LDRD projects are long and complex. “Some let us explore new areas that might fall outside our expertise with small seed projects to see if it will lead in a new direction,” Andy says. “This allows us to quickly explore areas that could become important in the future.”

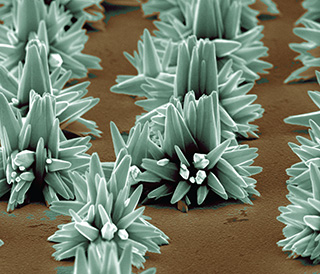

Andy says LDRD has produced groundbreaking work including discoveries and innovations in microelectronics, microsystems and nanondevices, materials science, defense, and advanced radar. “We’ve stayed at the forefront of radiation-hardened electronics. Sandia is one of the only places in the country that produces them,” he says. “It is important in nuclear weapons work but also applies to space-related activities.”

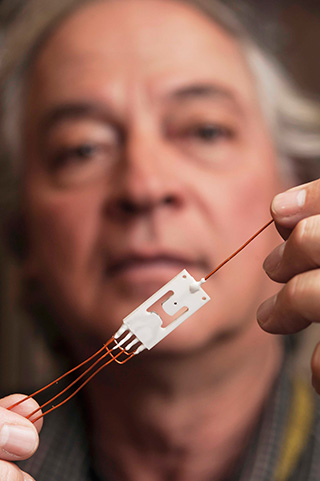

Bioscience was a niche at Sandia until LDRD advances led to the establishment of a research foundation. The breakthrough was MicroChemLab, a micro-laboratory compact and light enough to fit in a hand. It harnessed the power of a full chemistry lab, detecting and analyzing toxic agents such as bacteria, viruses, and protozoa in minutes rather than hours. And it did its work using only minuscule amounts of sample and analytes.

The micro device, created out of Sandia’s first Grand Challenge LDRD, was a milestone on a strategic path to establish the Labs as a microfluidics authority. Grand Challenges are larger LDRD projects at around $3 million a year for three years that focus on bold, high-risk ideas with potential for significant national impact. Sandia has enhanced the basic technology behind MicroChemLab, generated a multitude of patents, and garnered national recognition, including a 2012 R&D 100 award for an entire integrated system for automated sample preparation and analysis of micro-liter volumes.

And proving that innovation breeds innovation, MicroChemLab has spurred a half dozen startup companies and unanticipated uses such as monitoring for gases released during fracking. More than a decade after the first prototype was launched, the momentum remains strong as Sandia continues to receive funding for new applications of the microfluidics technology in national security, public health, and energy.

“This was an iconic project where an early investment in LDRD planted the seeds of an important national security program,” Andy says. “LDRD really helps us deliver on our tagline of delivering exceptional service in the national interest. To be exceptional we have to be at the cutting edge, and LDRD is one of the tools that help us meet the expectations of the country. We have delivered.”