Sandia has come up with an inexpensive way to synthesize titanium dioxide nanoparticles, and is seeking partners who could demonstrate the process at industrial scale for use in everything from solar cells to light-emitting diodes (LEDs).

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles show great promise as fillers to tune the refractive index of anti-reflective coatings on signs and optical encapsulants for LEDs, solar cells, and other optical devices. Optical encapsulants are coverings or coatings, usually made of silicone, that protect a device.

Industry has largely shunned TiO2 nanoparticles because they’ve been difficult and expensive to make, and current production methods produce particles that are too large.

Sandia became interested in TiO2 for optical encapsulants because of its work in LED materials for solid-state lighting.

Current production methods for TiO2 often require high-temperature processing and/or costly surfactants — molecules that bind to something to make it soluble in another material, like dish soap does with fat. Those methods produce less-than-ideal nanoparticles that are very expensive, can vary widely in size, and show significant particle clumping, called agglomeration.

Sandia’s technique, on the other hand, uses readily available low-cost materials and results in nanoparticles that are small and roughly the same size with no agglomeration.

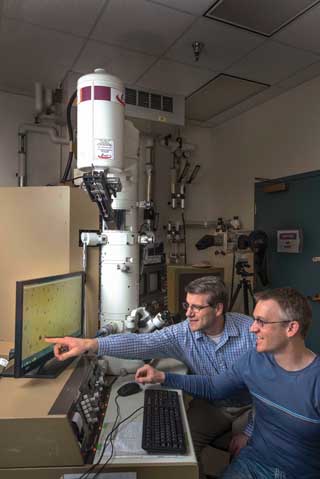

“We wanted something that was low cost and scalable, and that made particles that were very small,” says researcher Todd Monson (1114), who along with principal investigator Dale Huber (1132) patented the process in mid-2011 (Patent 7,943,116, “High-yield synthesis of brookite TiO2 nanoparticles”).

Technique produces small enough nanoparticles

Their method produces nanoparticles roughly 5 nanometers in diameter, approximately 100 times smaller than the wavelength of visible light, so there’s little light scattering, Todd says.

“That’s the advantage of nanoparticles — not just nanoparticles, but small nanoparticles,” he says.

Scattering decreases the amount of light transmission. Less scattering also can help extract more light, as in the case of an LED, or capture more light, in the case of a solar cell.

TiO2 can increase the refractive index of materials such as silicone in lenses or optical encapsulants. Refractive index is the ability of material to bend light. Eyeglass lenses, for example, have a high refractive index.

Practical nanoparticles must be able to handle different surfactants so they’re soluble in a wide range of solvents. Different applications require different solvents for processing.

“As an example, different polymers are soluble in different solvents. If someone wants to use TiO2 nanoparticles in a range of different polymers and applications, it’s convenient to have your particles be suspension-stable in a wide range of solvents as well,” Todd says. “Some biological applications may require stability in aqueous-based solvents, so it could be very useful to have surfactants available that can make the particles stable in water.”

The researchers came up with their synthesis technique by pooling their backgrounds — Dale’s expertise in nanoparticle synthesis and polymer chemistry and Todd’s knowledge of materials physics. The work was done under a Laboratory Directed Research and Development project Dale began in 2005.

Commercial applications were obvious

“The original project goals were to investigate the basic science of nanoparticle dispersions, but when this synthesis was developed near the end of the project, the commercial applications were obvious,” Dale says. The researchers subsequently refined the process to make particles easier to manufacture.

Existing synthesis methods for TiO2 particles were too costly and difficult to scale up production. In addition, chemical suppliers ship titanium dioxide nanoparticles dried and without surfactants, so particles clump together and are impossible to break up. “Then you no longer have the properties you want,” Todd says.

The researchers tried various types of alcohol as an inexpensive solvent to see if they could get a common titanium source, titanium isopropoxide, to react with water and alcohol.

The biggest challenge, Todd says, was figuring out how to control the reaction, since adding water to titanium isopropoxide most often results in a fast reaction and large chunks of TiO2, rather than nanoparticles. “So the trick was to control the reaction by controlling the addition of water to that reaction,” he says.

Some textbooks dismissed the titanium isopropoxide-water-alcohol method as a way of making TiO2 nanoparticles. Dale and Todd, however, persisted until they discovered how to add water very slowly by putting it into a dilute solution of alcohol. “As we tweaked the synthesis conditions, we were able to synthesize nanoparticles,” Todd says.

The next step is to demonstrate synthesis at an industrial scale, which will require a commercial partner. Todd, who presented the work at Sandia’s fall Science and Technology Showcase, says Sandia has had inquiries from companies interested in commercializing the technology.

“Here at Sandia we’re not really set up to produce the particles on a commercial scale,” he says. “We want them to pick it up and run with it and start producing these on a wide enough scale to sell to the end user.”

Sandia would synthesize a small number of particles, then work with a company to form composites and evaluate them to see if they can be used as better encapsulants for LEDs, flexible high-index refraction composites for lenses, or solar concentrators. “I think it can meet quite a few needs,” Todd says.