3.4.4. Discrete system of equations

The full approximate pressure projection scheme for non-uniform density is now written as

(3.793)

(3.794)

(3.795)

The variable is the residual that includes body source terms, pressure gradient, the non-symmetric part of the viscous stress term,

, parts of the time term and the left-hand side set of operators acting on the

state,

(3.796)

The mass matrix, , is defined by

(3.797)

The shape function above, , is frequently evaluated at

, the

coordinates of the vertex associated with the transport equation, i.e., the case where a lumped mass matrix is used.

For simplicity, the central difference operator is provided in as

(3.798)

In the preceding equation, the mass flow rate has been linearized within the iteration step and may or may not include the

explicit stabilization terms. Moreover, the shape function operator, , may be evaluated at the edge

midpoints to retain the skew symmetric aspect of the operator

. By default, this term is evaluated at the subcontrol surface

integration points, which retains the CVFEM canonical 27-point stencil.

The symmetric part of the stress tensor is given by

(3.799)

while the non-symmetric stress tensor is given by

(3.800)

Note that the nodal pressure gradient at node for control volume

for direction

is defined by

(3.754). The operator,

, contains the gravitational term as well as the

[potentially] subtracted out hydrostatic term,

(3.801)

The old time term contribution, , is defined by

(3.802)

Again, is the set of all subcontrol volume integration points

for control volume

,

is the set of all subcontrol surface integration points for control

volume

, and

is the set of all nodes within the element.

3.4.4.1. Predictor

In general, there are a number of predictors that are supported. The easiest predictor is a simple predictor in which the old value is mapped into the current iterate. Predictors that incorporate old time derivatives include the forward Euler and Adams-Bashforth methods, e.g.,

(3.803)

(3.804)

(3.805)

3.4.4.1.1. Upwind Interpolation for Convection

We currently support several upwind interpolations for convection. The upwind methods are blended with a centered scheme that becomes dominant below a specified cell-Peclet number.

3.4.4.2. First Order Upwind

The first scheme is a simple first-order scheme that considers the two nodes adjacent to a control volume face and extrapolates from the node in the upwind direction.

(3.806)

The convention is that flow leaves the control volume to the left (L) and enters the control volume to the right (R). If the mass flow rate at the face is negative in value, then the node to the right will be selected.

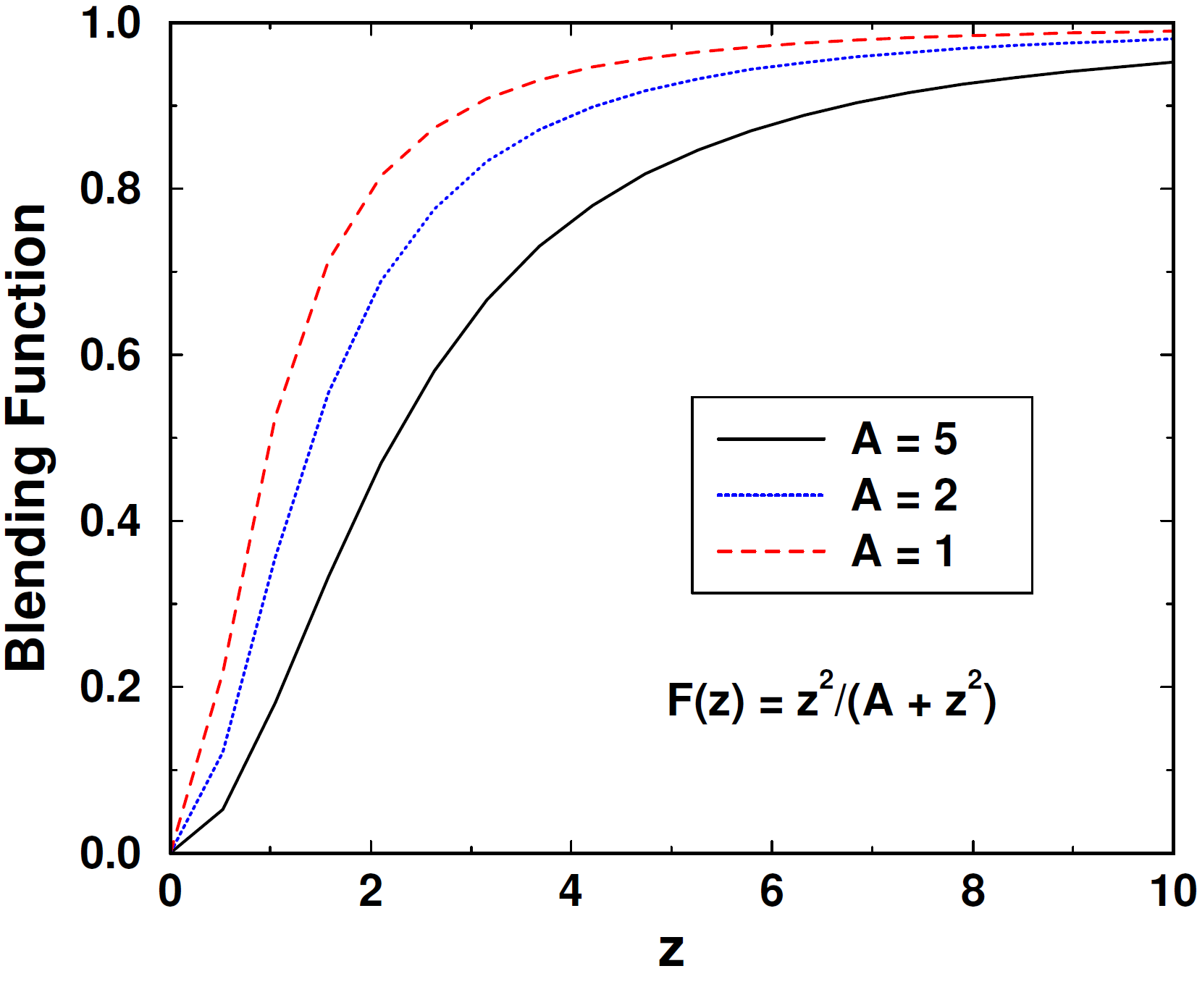

3.4.4.3. Blending Function

The user specified upwind factor controls the blending between the pure upwind operator and a blended user-chosen upwind/central operator.

(3.807)

where is the user specified first order upwind factor and

represents the user specified upwind operator,

e.g., MUSCL, modified skew upwind, and even pure upwind.

The centered average of is computed from the shape functions,

so it is based on all nodes in an element. The shape functions are

evaluated at the sub-face centroid.

The cell-Peclet number,

, is used in the blending

function (see Figure 3.29)

(3.808)

The hybrid upwind factor, , allows one to modify the functional

blending function; values of unity result in the normal blending function

response in Figure 3.29; values of zero yield

a pure central operator, i.e., blending function = 0.0; values

1 result

in a blending function value of unity, i.e., pure upwind. The constant

is implemented as above with a value of 5. This value can not be changed

via the input file.

The cell-Peclet number is computed for each sub-face in the element from the two adjacent left (L) and right (R) nodes.

(3.809)

A dot-product is implied by repeated indices.

Fig. 3.29 Cell-Peclet number blending function.

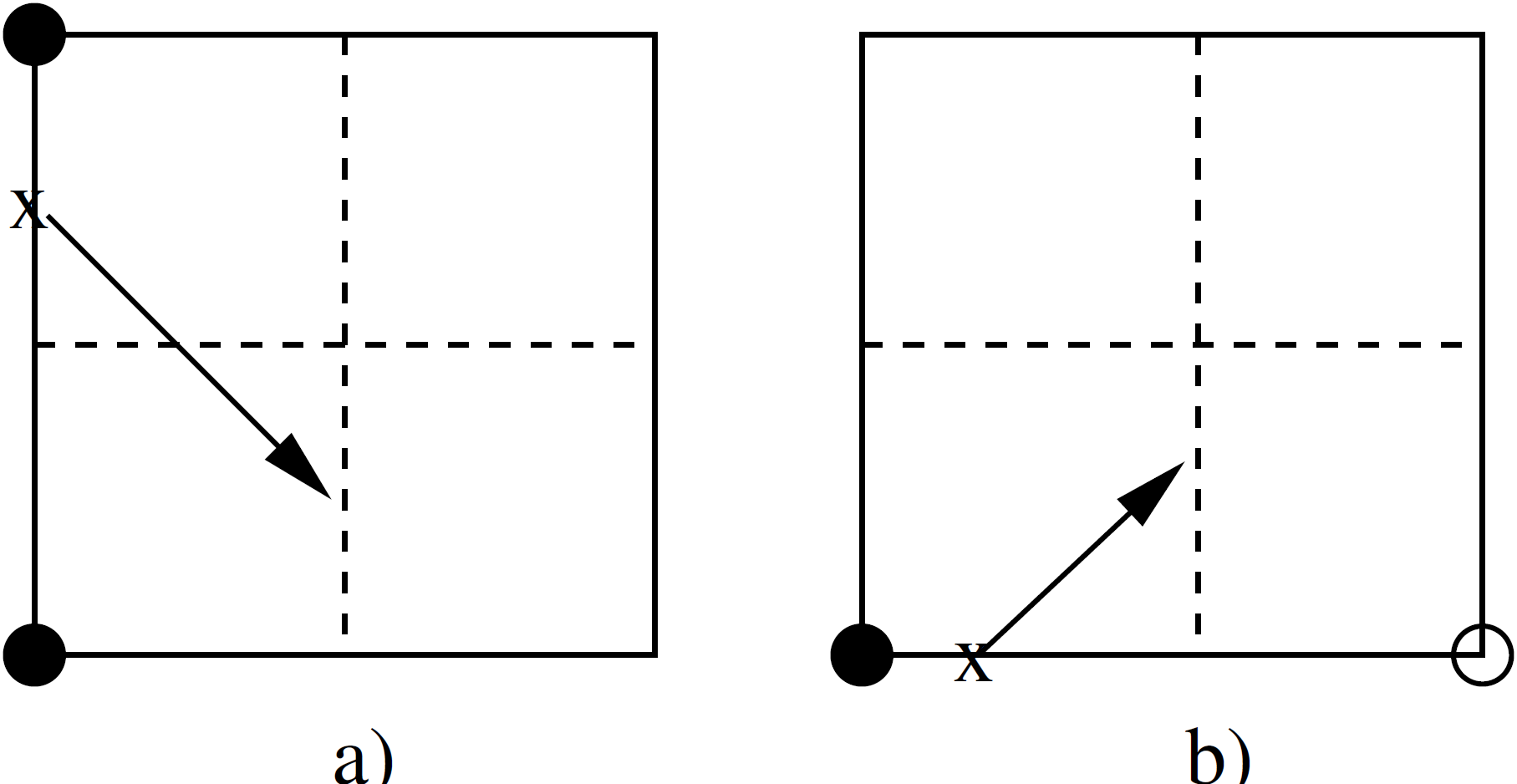

3.4.4.4. Modified Linear Profile Skew Upwind

Modified linear profile skew upwinding is a simplification to the skew upwinding approach in the FIELDS scheme [150, 151]. We omit the physical advection correction terms. Integration point values at control volume subfaces are interpolated from upwind intersection points on the element face. In the original skew upwind scheme, the intersection point could either be interior subface or element faces. The interpolation coefficients were computed by inverting a matrix relation between integration point values and nodal values. The linear profile skew upwinding does not use interior subface intersections – only element face intersections. The modified scheme throws out nodes on an element face that are downwind of an interior subface as shown in Figure 3.30.

Fig. 3.30 Linear profile skew upwind scheme: a) all nodes on the intersected element face are upwind of the subface, b) omit nodes on intersected element face that are downwind of the subface.

3.4.4.5. MUSCL

The MUSCL approach (see Chap. 21 of Hirsch [230]) for higher order

upwinding is adapted to unstructured meshes. The upwind interpolation is

constructed along each edge of an element. The interpolation makes use of

the two end nodes of the edge and the centered gradient constructed at the two

end nodes. The MUSCL approach constructs an interpolation in one dimension

from four (or more) uniformly distributed nodal values. The two edge nodes are

and

. The two other nodal values,

and

, are interpolated from the unstructured mesh using the nodal

gradient information.

The MUSCL scheme constructs left and right interpolants at the subface of the control volume. Without the limiter functions, the interpolation is

(3.810)

(3.811)

where the location is between node

and node

.

On a uniform mesh,

gives a third-order scheme. A second-order

upwind scheme is recovered with

and a centered scheme is

recovered with

.

Limiter functions are introduced to prevent numerical oscillations from occurring.

(3.812)

(3.813)

where

(3.814)

(3.815)

The limiters are selected to be symmetric such that

(3.816)

The limited interpolation functions are

(3.817)

(3.818)

The interpolation for the points off the element edge is

(3.819)

(3.820)

where is the distance vector along the element edge.

Symmetric limiter functions are:

(3.821)

(3.822)

(3.823)

3.4.4.6. Convection at an Inflow and Outflow Boundary

At an open boundary, the first-order and LPS upwind schemes only make use of information on the boundary.

For the MUSCL scheme with the flow leaving the domain at node ,

the usual flux limiters are not used. The slopes are compared

between

and

.

If the slopes are the same sign, the unlimited second order upwinding

is used. If the slopes are different, then a local interpolation is used.

Estimate the slope

,

where

is

the distance vector along the element edge.

For slopes of the same sign, use a second-order scheme,

(3.824)

else, use a first-order scheme,

(3.825)

The boundary is the left (L) side.

If the flow enters the domain, then use the local value of .

3.4.4.7. Nonlinear stabilization operator

The “nonlinear stability operator” (NSO) in Fuego is an artificial viscosity method where the added diffusivity is based on a scaled, pointwise evaluated residual. For a dual volume (), associated with a node

, the weak form of the NSO for a scalar variable

is

(3.826)

where depends on the evaluation of a local residual

and the gradient of

as

(3.827)

The local residual can be taken, similar to Shakib:cite:Shakib:1991 but in an incompressible context, as the full residual of the PDE. For a conserved scalar,:math:q, with diffusivity ,

would be

(3.828)

with discrete operators representing the individual terms of the advection-diffusion equation. For an equation with a source term, it would also need appear in the local residual calculation. Another possibility for choosing would be based on the error of performing the chain-rule on the advection operator.

(3.829)

where and

represent interpolation and gradients evaluated at an integration point. Both options are available in Fuego.

The NSO computed from such residuals can add an unnecessarily large amount of dissipation in some cases. For this reason, we limit the NSO coefficient to the upwind value as

(3.830)

where . Additionally, as it’s based on the mesh discretization error, the NSO coefficient tends to vary strongly on short length scales. For numerical robustness, we average the NSO viscosity over control volumes, and then interpolate back to the subcontrol surfaces to evaluate the diffusion term; that is,

(3.831)

This operation effectively smooths the NSO viscosity over a patch of elements. The nonlinear stabilization viscosity is not included at the boundaries.

3.4.4.7.1. Variable Density

The discretization of the time derivative requires special attention for variable density flows. The density time-derivative in the continuity equation must be predicted in a continuous manner. The density at the new time level in the convection terms and the transport equation time terms must also be predicted.

The transport equations are solved in conservative form, so density appears in the time derivative. With a segregated solution strategy, the density at the new time level is not available until the transport equations have been solved once. A density predictor is required. A generic time term is written as

(3.832)

There are two approaches to estimating the new density.

The simplest approach is to use the most recent value.

The other approach is to use a density predictor.

The predicted value of density at the new time level, ,

is computed from the old density and the current density

time derivative. Introduce the nodal variable

for the discrete

density time-derivative such that

(3.833)

(3.834)

The density derivative, ,

is always updated at the bottom of the transport equation loop

after a new set of temperatures and mass fractions is available.

The two approaches are different for the first nonlinear sub-iteration

within a time step, but yield equivalent values upon subsequent

sub-iterations. The new density is also computed at the bottom

of the equation loop. This value is ignored upon subsequent

sub-iterations if using the density predictor. But, this

new density value will get copied to the old time level when

the time step is advanced. It is important to note that this

new “old” velocity is not consistent with the density that

was used in the old transport equations, but it seems critical

to the success of this approach to do so.

For the first nonlinear iteration within a time step, the effect of the density at the new time level is predicted by carrying forward the best approximation of the density time-derivative from the last time step. The continuity equation is implemented as

(3.835)

where the density time-derivative is the most recent value and the

density in the convection is estimated in the same manner as the

transport equations. The density time-derivative, ,

must be stored as a persistent nodal variable in order

to have a good estimate for the continuity equation from

step to step.

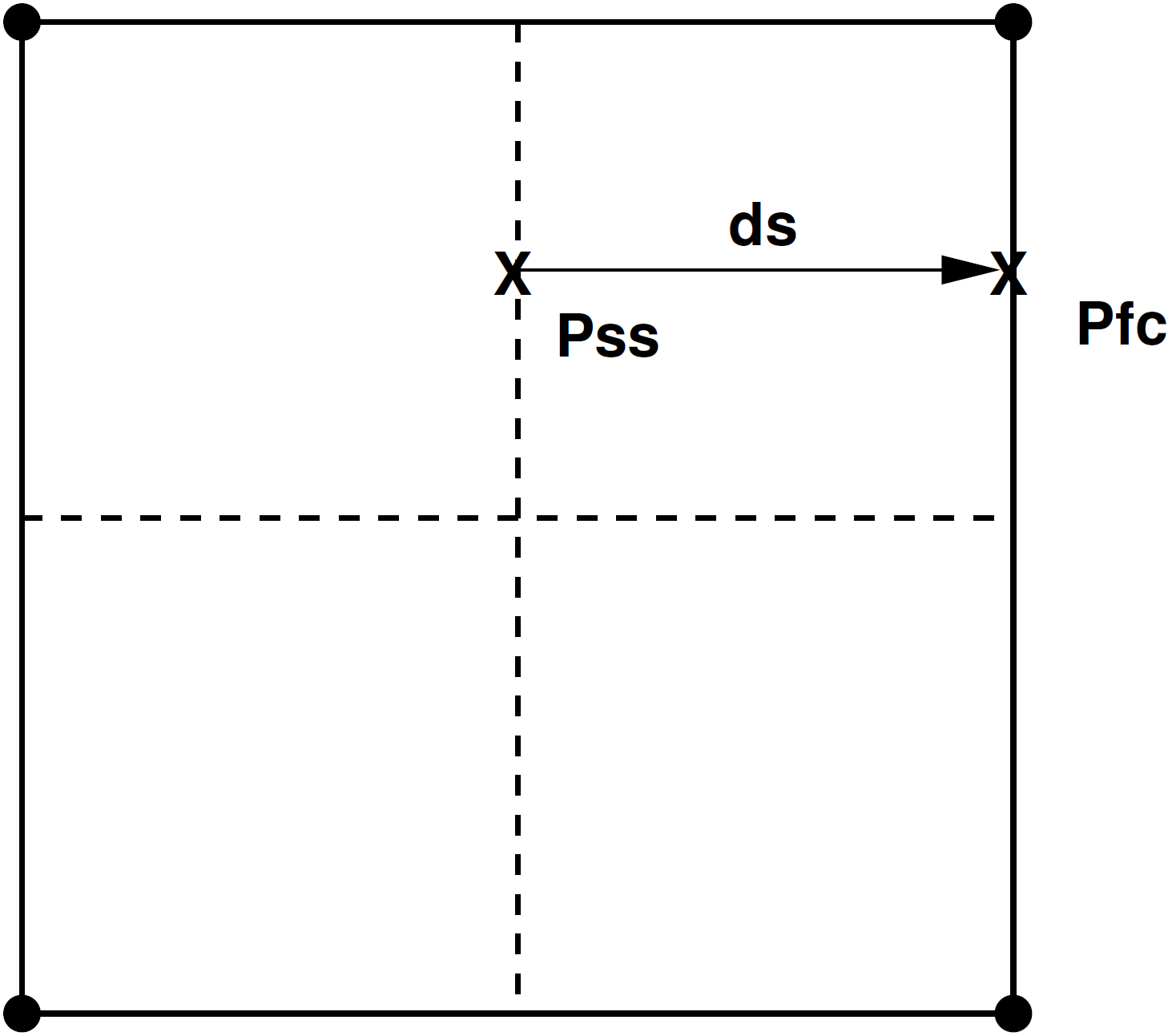

3.4.4.7.2. Open Boundary Conditions

Open boundary conditions are used for boundaries where the flow can go either in or out. The direction of the flow is determined by the local force balance. In this documentation, the open boundary condition is also referred to as the outflow boundary condition. There are two parts to the outflow boundary condition. The first part concerns computing a velocity field that satisfies continuity. The second part concerns selecting the proper convected scalar value depending if the flow is in or out of the domain. Control volume balances are implemented at open boundaries for continuity, momentum, and the other transport equations.

Fig. 3.31 Boundary mass flux integration locations.

A fixed pressure value is specified for the continuity and momentum equations. The nodal values of pressure on the boundary are allowed to float. A mass flux condition is formulated at the boundary in order to drive the boundary pressures towards the specified boundary pressure and to provide a boundary mass flow rate for the other transport equations. The form of the boundary mass flux is similar to the pressure-stabilized interior mass fluxes (see section Flow Solver). The equation for the mass flux at a boundary face, shown in Figure 3.31, is

(3.836)

and the interpolation formula for a single velocity component is

(3.837)

The upper case velocities, , are nodal velocities, while the

lower case velocity,

, is the boundary velocity.

The average pressure,

, is computed at the opposing subface

centroid and evaluated at the new time level,

. The boundary

pressure,

, is evaluated at the boundary subface centroid

and is the “specified” pressure. The operator,

, is the

discrete gradient operator for node

. In the case of the semi-discrete

formulation, the last term is dropped in (3.837)

and

.

The nodal pressure gradient is required for the momentum balance and

the boundary mass flux formulation. The nodal pressure gradient is

constructed by a discrete Gauss divergence relation over the control

volumes. The pressure at most control volume subfaces is interpolated

from the nodes of the parent element, even over inflow, wall, and

symmetry boundaries. For outflow boundaries, the specified boundary

pressure, , is used.

Nodal velocities on open boundaries are corrected with the projection.

On pressure-specified open boundaries, the flow will sometimes exit and reenter the domain through some sort of entrainment process. The process will look non-physical and is due to the artificially imposed constant pressure. A method of counteracting the reentrance problem is to turn off the convection terms in the momentum equations for control-volume subfaces which have reentrant flow. This condition is optional and can be set on a side-set basis.

If the flow is entrained into the domain, then far-field values must be specified for the scalar variables.