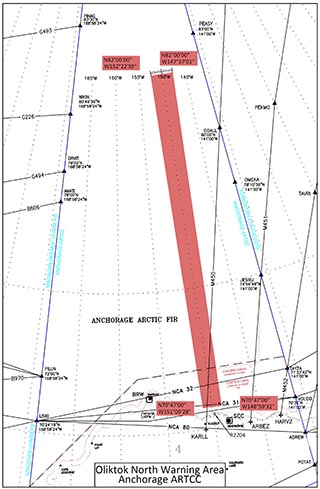

The red bar depicts the 40-mile-wide, 700-mile-long Warning Air Space now under management by Sandia personnel for DOE’s Atmospheric Radiation Measurement facilities. The space, approved by the Federal Aviation Administration after a five-year review, extends from Oliktok Point, the northernmost point of the US highway system, to 400 miles short of the North Pole. The monitored space will better ensure the safety of climate and other experiments taking place over international waters in the Arctic.

The Coast Guard, oil companies, climate researchers, and unmanned aircraft and robotic vehicle manufacturers all share an interest in the changing Arctic.

Helping further those interests, Sandia researcher Mark Ivey (6913) and Sandia colleagues worked closely with DOE program managers in the Office of Science to secure formal approval for a block of Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) special-use air space. On May 28, FAA published notice of W-220, a new Warning Area in which Sandia-approved

participants can gather data on clouds and atmospheric constituents, practice search-and-rescues at sea, and track the northward movement of retreating sea ice.

“Everyone needs a space to work,” says Mark.

The 40-mile-wide, 700-mile-long air space stretches from just offshore at Oliktok Point, the northern end of the road system on the North American continent, to about 400 miles short of the North Pole.

The authorization by FAA rewarded roughly five years of patient effort by Mark, his team, and their program managers who supported the efforts. “In 2004, we were granted a 4-mile-diameter Restricted Area around Oliktok Point, our base of operations for atmospheric measurements,” Mark says. Restricted areas are established in US airspace; warning areas apply to international airspace. “That was renewed in 2010. But we saw the possibility of more extensive, ongoing experiments, with renewed interest in operating offshore.”

Careful consideration by FAA

Still, it was clear to everyone involved that tethered, sensor-laden balloons hanging invisibly in a low cloud would present a danger to aircraft, particularly the many small and privately operated aircraft in Alaska.

So Mark, along with his predecessor, retired Sandia climate researcher Bernie Zak, applied and reapplied, revised, and reapplied again on behalf of DOE to be granted the larger air space, which extends over international waters and provides a significant safety margin to experimenters by warning pilots who might be considering entering the area.

The FAA’s hesitations, Mark says, weren’t arbitrary. “The FAA looks at these requests pretty carefully because if they didn’t, the whole country could soon be carved up into restricted air space, making flying a nightmare.”

Barrow, the other hub of activity for Mark’s team on the North Slope of Alaska, was too busy an aviation area to be considered for special-use air space. But even at remote Oliktok Point, pilots protested at a meeting hosted by the FAA. “They said there’s roughly 1,000 miles of coastline in the Alaskan Arctic with only two instrumented airports, Deadhorse and Barrow. ‘Look what you’re doing,’ they said, ‘these two instrumented airports are on either side of your proposed warning area. Suppose a pilot has a problem and one airport is fogged in; how does the pilot get to the other airport?’”

A smaller set of fences

To solve the problem, the warning area was divided into 16 areas: eight horizontal areas, each with two vertical layers. One vertical layer extends from zero to 2,000 feet and the other from 2,000 feet to 10,000 feet. For further ease of transport, eight subdivisions extend south to north. “That created a smaller set of fences that people can get around if they need to,” Mark says. “We also worked out ways that pilots could contact us to find out where current research activities were located.”

Then the question was raised in committee as to whether the warning area boundaries should follow longitudinal lines, so it would get smaller as it approached the Pole, dovetailing with Canada and Russia. After discussion, the area was set at 40 miles across from north to south. The area therefore stops short of the Pole to avoid intruding on the airspace of other countries.

“I saw gaining the warning area as a big win for DOE’s Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) facilities, because it opens up the Arctic for new Office of Science research efforts,” says Mark. “It makes it possible to do things out there it wouldn’t be possible to do otherwise."

The facility, according to a description from DOE, “is hosting a research campaign designed to demonstrate how small, low-cost, unmanned aerial systems can be used to study and measure clouds and aerosols in the cold and harsh Arctic atmosphere.”

Sandia, which started the Arctic effort, now manages Oliktok Point for the Office of Science and the ARM Program, because, Mark says, "the FAA awards special-use airspace only to other federal agencies."

But other users have other interests. The first proj-ect to make use of the restricted air space is the Coast Guard Research and Development Center’s (RDC) Arctic Technology Evaluation 2015 search-and-rescue exercise (SAREX), a Cooperative Research and Development (CRADA) initiative involving the oil company ConocoPhillips and the Coast Guard Research and Development Center. Other partners include Insitu/Boeing, Era Helicopters, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and multiple operational Coast Guard units. All these entities are working with Sandia on a joint effort that involves interoperability between manned and unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), sometimes referred to as drones, to conduct search and rescue operations.

Looking for Thermal Oscar

“The Coast Guard is concerned about search-and-rescue in the Arctic; they haven’t had a year-round presence there but they’re interested,” says Mark. “What’s changed in recent years is a lot of near-shore oil exploration and production activity, including helicopter operations.”

For the exercise, Coast Guard Cutter Healy deployed a six-person life raft and Thermal Oscar, an RDC-developed floating dummy outfitted with a heat source that makes it visible to infrared sensors, as search-and-rescue (SAR) targets for the UAS to locate. The UAS launched from land at Oliktok Point and transited out to the special-use airspace via an altitude reservation established by the FAA. Control of the UAS was passed to operators on CGC Healy to execute a search action plan to locate the SAR targets. Once the UAS was over the targets, CGC Healy passed their position to manned aircraft on shore and vectored the aircraft in for recovery efforts.

“It’s testing rescue communications, among other things. Here on the North Slope, we don’t have the satellite coverage or the infrastructure of the lower 48,” says Mark. “Somewhere offshore, Insitu/Boeing passed control of ScanEagle to someone on the Healy, which is a big deal in the drone world, takes nontrivial technology, and could be important in future search-and-rescues.”

The technology and practices implemented during Arctic Shield will provide useful information for future ARM/DOE UAS research activities, says Mark. “For example, electronics technologist Todd Houchens (6913) monitored radar scopes at NORAD during Arctic Shield to check air traffic near Oliktok point prior to UAS launch, and two FAA representatives on site at Oliktok provided helpful suggestions for future operations.

“And the whole event is taking place as safely as possible within this new warning area,” Mark says.

For more information about ARM, see www.arm.gov.