Reports by scientists of meteorites striking Earth generally resemble police reports of too many muggings — the offenders came out of nowhere and then disappeared into the crowd, making it difficult to get more than very basic facts.

Now for the first time, an international research team identified an asteroid in space before it entered Earth’s atmosphere, enabling computers to determine its area of origin in the solar system as well as predict the arrival time and location on Earth of its shattered surviving parts.

“I would say that this work demonstrates, for the first time, the ability of astronomers to discover and predict the impact of a space object,” says Mark Boslough (1433), a member of the research team.

Perhaps more importantly, the event tested the ability of society to respond very quickly to a predicted impact, says Mark. “In this case, it was never a threat, so the response was scientific. Had it been deemed a threat — a larger asteroid that would explode over a populated area — an alert could have been issued in time that could potentially save lives by evacuating the danger zone or instructing people to take cover.”

The profusion of information also satisfied a desire by meteoriticists to know the orbits and locations of parent bodies that yield meteorites of various types, he says. Such knowledge could help future space missions explore or even mine the asteroids in Earth-crossing orbits.

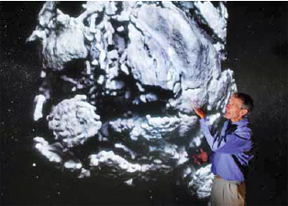

The four-meter-diameter asteroid, called 2008 TC3, was initially sighted by the automated Catalina Sky Survey telescope at Mount Lemmon, Ariz., on Oct 6. Numerous observatories, alerted to the invader, then imaged the object. Computations correctly predicted impact would occur in the Nubian Desert of northern Sudan 19 hours after discovery.

According to NASA’s Near Earth Object program, “A spectacular fireball lit up the predawn sky above Northern Sudan on Oct. 7, 2008.”

A wide variety of analyses were performed while the asteroid was en route and after its surviving pieces were located in an intense search by meteorite hunters.

Researchers listed in the paper describing this work in the cover article of the March 26 issue of the journal Nature come from the SETI Institute, the University of Khartoum, Juba University (Sudan),

Sandia, Caltech, NASA Johnson Space Center and NASA Ames, and other universities in the US, Canada, Ireland, England, Czech Republic, and the Netherlands.

Dick Spalding (5710) interpreted data that recorded the atmospheric fireball, and Mark estimated the aerodynamic pressure and strength of the asteroid based on the estimated burst altitude of 36 kilometers.

Searchers have recovered 47 meteorites so far— offshoots from the disintegrating asteroid, mostly immolated by its encounter with atmospheric friction — with a total mass of 3.95 kilograms.

The analyzed material showed carbon-rich materials not yet represented in meteorite collections, indicating that fragile materials still unknown may account for some asteroid classes. Such meteorites are less likely to survive due to destruction upon entry and weathering once they land on Earth’s surface.

“Chunks of iron and hard rock last longer and are easier to find than clumps of soft carbonaceous materials,” says Mark.

“We knew that locating an incoming object while still in space could be done, but it had never actually been demonstrated until now,” says Mark. “In this post-rational age where scientific explanations and computer models are often derided as ‘only theories,’ it is nice to have a demonstration like this.”