6.2. Element Sections

Element sections are defined by section command blocks. There are currently 11 different types of section command blocks. The section command blocks appear in the SIERRA scope, at the same level as the FINITE ELEMENT MODEL command block. In general, a section command block has the following form:

BEGIN section_type SECTION <string>section_name

{command lines dependent on section type}

END [section_type SECTION <string>section_name]

Currently, section_type can be SOLID, COHESIVE, SHELL, MEMBRANE, BEAM, TRUSS, SPRING, DAMPER, POINT MASS, PARTICLE, or SUPERELEMENT. These various section types are identified as individual section command blocks and are described below. The corresponding section_name parameter in each of these command blocks, e.g., truss_section_name in the TRUSS SECTION command block, is selected by the user. The method used to associate these names with individual SECTION command lines in PARAMETERS FOR BLOCK command blocks is discussed in Section 6.1.7.5.

Following is a list of most of the different element formulations that are offered in Sierra/SM. The sections are colored bold, red, and blue based on where the documentation can be found. Bold sections do not have any documentation posted; prospective users should contact a developer before use. Red sections can be found in the Sierra/SM Capabilities in Development manual. Blue links to the relevant section in this manual.

Element |

# nodes |

Section |

Formulation |

|---|---|---|---|

ANY |

ANY |

||

ANY |

ANY |

||

Sphere |

1 |

|

|

Sphere |

1 |

SPH |

|

Sphere |

1 |

POINT MASS |

|

BAR |

2 |

||

BAR |

2 |

|

|

BAR |

2 |

||

BAR |

2 |

||

BAR |

2 |

|

|

BAR |

2 |

||

BAR |

2 |

SPRING SUPPORT |

|

BAR |

2 |

||

BAR |

2 |

Element |

# nodes |

Section |

Formulation |

Strain Incrementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Shell |

3 |

ORIG_TRI_SHELL |

MIDPOINT_INCREMENT |

|

Shell |

3 |

ORIG_TRI_SHELL |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

|

Shell |

3 |

C0_TRI_SHELL |

MIDPOINT_INCREMENT |

|

Shell |

3 |

C0_TRI_SHELL |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

|

Shell |

4 |

|||

Shell |

4 |

MEAN_QUADRATURE |

MIDPOINT_INCREMENT |

|

Shell |

4 |

MEAN_QUADRATURE |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

|

Shell |

4 |

SELECTIVE_DEVIATORIC |

MIDPOINT_INCREMENT |

|

Shell |

4 |

NQUAD |

||

Shell |

4 |

BT_SHELL |

MIDPOINT_INCREMENT |

|

Shell |

4 |

KH_SHELL |

MIDPOINT_INCREMENT |

|

Shell |

4 |

KH_SHELL |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

|

Shell |

4 |

BL_SHELL |

MIDPOINT_INCREMENT |

|

Shell |

4 |

BL_SHELL |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

|

TETRA |

MEAN_QUADRATURE |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

||

TETRA |

MEAN_QUADRATURE |

NODE_BASED |

||

TETRA |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

||

TETRA |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

NODE_BASED |

||

TETRA |

VOID |

|||

PYRAMID |

5 |

MEAN_QUADRATURE |

MIDPOINT_INCREMENT |

|

PYRAMID |

5 |

MEAN_QUADRATURE |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

|

PYRAMID |

5 |

MEAN_QUADRATURE |

TOTAL_LAGRANGE |

|

WEDGE |

6 |

|||

WEDGE |

6 |

|||

WEDGE |

6 |

MEAN_QUADRATURE |

MIDPOINT_INCREMENT |

|

WEDGE |

6 |

MEAN_QUADRATURE |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

|

WEDGE |

6 |

MEAN_QUADRATURE |

TOTAL_LAGRANGE |

|

HEX |

8 |

|||

HEX |

8 |

|||

HEX |

8 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

||

HEX |

8 |

MEAN_QUADRATURE |

MIDPOINT_INCREMENT |

|

HEX |

8 |

MEAN_QUADRATURE |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

|

HEX |

8 |

MEAN_QUADRATURE |

TOTAL_LAGRANGE |

|

HEX |

8 |

SELECTIVE_DEVIATORIC |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

|

HEX |

8 |

VOID |

||

TETRA |

8 |

NOT SUPPORTED |

||

TETRA |

10 |

(NONE_SPECIFIED = COMPOSITE_TET) |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

|

TETRA |

10 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

||

HEX |

20 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

|

HEX |

27 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

Element |

# nodes |

Formulation |

Strain Incrementation |

cubature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

TETRA |

4 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING |

1 |

TETRA |

4 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

1 |

TETRA |

4 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING |

2 |

TETRA |

4 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

2 |

TETRA |

4 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING |

3 |

TETRA |

4 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

3 |

HEX |

8 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING |

ANY |

HEX |

8 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

ANY |

TETRA |

10 |

COMPOSITE_TET |

LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING |

2 |

TETRA |

10 |

COMPOSITE_TET |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

2 |

TETRA |

10 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING |

2 |

TETRA |

10 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

2 |

TETRA |

10 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING |

3 |

TETRA |

10 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

3 |

TETRA |

10 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING |

4 |

TETRA |

10 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

4 |

PYRAMID |

13 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING |

ANY |

PYRAMID |

13 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

ANY |

WEDGE |

15 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING |

ANY |

WEDGE |

15 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

ANY |

HEX |

20 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING |

ANY |

HEX |

20 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

ANY |

HEX |

27 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING |

3 |

HEX |

27 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

3 |

HEX |

27 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING |

5 |

HEX |

27 |

FULLY_INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE |

5 |

Solid Element Type |

Section Type |

Formulation |

Strain Formulation |

|---|---|---|---|

HEX8 |

SOLID |

MEAN QUADRATURE |

MIDPOINT INCREMENT |

HEX20 |

SOLID |

FULLY INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY OBJECTIVE |

HEX27 |

SOLID |

FULLY INTEGRATED |

STRONGLY OBJECTIVE |

TET4 |

SOLID |

MEAN QUADRATURE |

STRONGLY OBJECTIVE |

TET10 |

TOTAL LAGRANGE |

COMPOSITE TET |

STRONGLY OBJECTIVE |

WEDGE6 |

SOLID |

MEAN QUADRATURE |

MIDPOINT INCREMENT |

PYRAMID5 |

SOLID |

MEAN QUADRATURE |

MIDPOINT INCREMENT |

6.2.1. Solid Section

BEGIN SOLID SECTION <string>solid_section_name

RVE COORDINATE SYSTEM = <string>Coordinate_system_name

FORMULATION = <string>MEAN_QUADRATURE|SELECTIVE_DEVIATORIC|

FULLY_INTEGRATED|VOID(MEAN_QUADRATURE)

DEVIATORIC PARAMETER = <real>deviatoric_param

STRAIN INCREMENTATION = <string>MIDPOINT_INCREMENT|

STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE|NODE_BASED|TOTAL_LAGRANGE(depends)

STRESS MEASURE = CAUCHY|HENCKY(CAUCHY)

NODE BASED ALPHA FACTOR = <real>bulk_stress_weight(0.01)

NODE BASED BETA FACTOR = <real>shear stress_weight(0.35)

NODE BASED STABILIZATION METHOD = <string>EFFECTIVE_MODULI|

MATERIAL(MATERIAL)

HOURGLASS FORMULATION = <string>TOTAL|INCREMENTAL|

HYPERELASTIC(INCREMENTAL)

HOURGLASS INCREMENT = <string>ENDSTEP|MIDSTEP (ENDSTEP)

HOURGLASS ROTATION = <string> APPROXIMATE|SCALED (APPROXIMATE)

RIGID BODY = <string>rigid_body_name

RIGID BODIES FROM ATTRIBUTES = <integer>first_id

TO <integer>last_id

MASS LUMPING METHOD = DEFAULT|ROWSUM|EVEN (DEFAULT)

END [SOLID SECTION <string>solid_section_name]

The SOLID SECTION command block specifies the properties for solid elements (hexahedra and tetrahedra). This command block is to be referenced by an element block made up of solid elements. The two types of solid-element topologies currently supported are hexahedra and tetrahedra. The parameter solid_section_name is user-defined and is referenced by a SECTION command line in a PARAMETERS FOR BLOCK command block.

The RVE COORDINATE SYSTEM command line specifies the name of a coordinate system definition block command used to define a local coordinate system on each element of a block that uses this SOLID SECTION. This coordinate system only has an effect on RVE analysis (see the Sierra/SM Capabilities in Development manual for details).

The FORMULATION command line specifies whether the element will use a single-point integration rule (mean quadrature), a selective-deviatoric rule, a selectively integrated rule, or a fully-integrated rule, or act as a void element. The selective-deviatoric and fully-integrated integration rules are higher-order integration schemes, which are discussed below.

If the user wishes to use the selective-deviatoric rule, the DEVIATORIC PARAMETER command line must also appear in the SOLID SECTION command block.

Choosing the SELECTIVE_DEVIATORIC formulation indicates that the element is fully integrated with respect to the deviatoric stress response and under integrated with respect to the hydrostatic pressure response. The under-integration of the hydrostatic pressure response is achieved through averaging the pressure over the integration points. The SELECTIVE_DEVIATORIC formulation is often used to alleviate volumetric locking associated with isochoric motion. By default, this formulation involves no hourglass control. However, the user may include an additional input command within the element section, DEVIATORIC PARAMETER, which may set deviatoric_param between 0.0 and 1.0, and which blends an under-integrated deviatoric stress field (DEVIATORIC PARAMETER = 0.0) with a fully-integrated deviatoric stress field (DEVIATORIC PARAMETER = 1.0). Setting a value of 0.0 results in an under-integrated element type without any hourglass control, and is not recommended. By default, this parameter is set to 1.0, which is the recommended value in almost all circumstances. Lower values, ideally not less than 0.5, may improve convergence or accuracy in some very specific circumstances.

The selective-deviatoric elements, when used with a value greater than 0.0, provide hourglass control without artificial hourglass parameters.

Alternatively, a fully-integrated rule can be defined by setting FORMULATION = FULLY_INTEGRATED. This will apply an eight-point integration scheme for eight-noded hexahedral elements and a four-point integration scheme for ten-noded tetrahedral elements. This definition is currently unavailable for four-noded and eight-noded tetrahedral elements.

The VOID formulation is valid for 8-node hexahedral and 4-node tetrahedral element blocks. Void elements only compute volume. They do not contribute internal forces to the model. The material model and density associated with void elements are ignored. The volume and the first and second derivatives of the volume for each element are stored in the element variables volume, volume_first_derivative, and volume_second_derivative. The volume derivatives are computed using least squares fits of the volume history, which is stored for the previous five time steps.

In addition to the per-element volume and derivatives, the total volume and derivatives of that total volume for all elements in each void element block are written to the results file as global variables. The names for these variables are voidvol_blockID, voidvol_first_deriv_blockID, and voidvol_second_deriv_blockID. In these global variable names, blockID is the ID of the block. For example, the void volume for block 8 would be stored in voidvol_8.

The STRAIN INCREMENTATION command defines the strain incrementation formulation to use for solid element types that support multiple formulations. The element summary at the beginning of Section 6.1 specifies the strain incrementation formulations available for each element. Many elements have two choices for the strain incrementation formulation: MIDPOINT_INCREMENT or STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE. Generally, the midpoint-increment formulation is slightly faster and the strongly-objective formulation is slightly more accurate. Consult [[1], [2]] for descriptions of these strain formulations.

The four-noded tetrahedron has a NODE_BASED option for the STRAIN INCREMENTATION, which indicates usage of the node-based tetrahedron (see Section 6.2.1.1).

The eight-noded mean-quadrature hexahedron has a TOTAL_LAGRANGE option for the STRAIN INCREMENTATION, which is based on the total deformation and is provided for usage with the HYPERELASTIC hourglass formulation.

The STRESS MEASURE option is specifically for the eight-noded mean-quadrature hexahedron with the TOTAL_LAGRANGE strain incrementation and the HYPERELASTIC hourglass formulation. The HENCKY option is slightly more accurate for the hyperelastic hourglass formulation, but CAUCHY (the default) is necessary for optimal compatibility with the material models.

The HOURGLASS FORMULATION command is used to switch between total, hyperelastic and incremental forms of hourglass control. The total hourglass option can only be used with eight-noded mean-quadrature hexahedral elements using strongly objective strain incrementation (STRAIN INCREMENTATION = STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE). In contrast, the hyperelastic hourglass option can only be used with eight-node mean-quadrature hexahedral elements using total-Lagrange strain incrementation (STRAIN INCREMENTATION = TOTAL_LAGRANGE). One of the following three arguments can be used with this command: TOTAL, HYPERELASTIC, or INCREMENTAL.

The total formulation performs stiffness hourglass force updates based on the rotation tensor from the polar decomposition of the total deformation gradient. The hyperelastic formulation computes hourglass strains relative to the reference/model configuration, and has a well defined hyperelastic hourglass strain energy; as a result this formulation results in a symmetric contribution to the stiffness matrix, is fully reversible, and allows for a nonlinear hourglass resistance. The incremental formulation is the default and performs stiffness hourglass force updates based on the hourglass velocities and the incremental rotation tensor. The viscous hourglass forces and the hourglass parameters are unchanged by this command. Consult the element documentation [[2]] for a description of the hourglass forces and the incremental hourglass formulation.

The HOURGLASS INCREMENT and HOURGLASS ROTATION commands control the speed and accuracy of the hourglass control computation. These commands are only applicable to the mean-quadrature hexahedron with midpoint strain incrementation ({STRAIN INCREMENTATION = MIDPOINT_INCREMENT). The HOURGLASS INCREMENT line command specifies whether the hourglass resistance increment is to be computed at the middle or end of the time step. The end-step calculation has a slightly reduced computational cost while the mid-step computation is more accurate. The default is ENDSTEP. The HOURGLASS ROTATION command controls whether the hourglass resistance will be scaled after rotation to preserve the magnitude. Scaling requires additional computation time but will be more accurate, particularly when large rotations are present in the analysis. The default is APPROXIMATE, meaning no scaling is done.

Rigid elements in a section are indicated by including the RIGID BODY command line. The RIGID BODY command line specifies an identifier that maps to a rigid body command block. See Section 6.3.1 for a full discussion of how to create rigid bodies and Section 6.3.1.1 for information on the use of the RIGID BODIES FROM ATTRIBUTES command.

Known Issue

For problems with large rotations the hourglass energies are known to spike exponentially with increases in total rotation. This may be due to a coupling with hypoelastic material models.

6.2.1.1. Node-Based Tetrahedra

The node-based formulation can only be used with four node tetrahedral elements. If the element-block (i.e., PARAMETERS FOR BLOCK) command block has a SECTION command line that references a SOLID SECTION command block that uses

STRAIN INCREMENTATION = NODE_BASED

then the tetrahedral element block will use the node-based tetrahedron formulation.

The node-based formulation calculates a solution that is a mixture of an element-based formulation (information from the center of an element) and a node-based formulation (information at a node that is based on the average of all elements attached to the node). The node-based tetrahedron allows a model with four-node tetrahedral elements to avoid most of the locking problems of regular tetrahedral elements. Regular tetrahedral elements are much too stiff and can produce inaccurate results in many situations.

The mixture of node-based versus element-based information incorporated into the solution may be adjusted with the NODE BASED ALPHA FACTOR and NODE BASED BETA FACTOR command lines. These two lines apply only if the NODE_BASED option is specified on the STRAIN INCREMENTATION command line. The value for bulk_stress_weight on the NODE BASED ALPHA FACTOR command line sets the element bulk stress weighting factor, while the value for shear_stress_weight on the NODE BASED BETA FACTOR command line sets the element shear stress weighting factor. The weighting factors are described in detail in [[3]]. A strictly node-based formulation results when both factors are set to zero, while a strictly element-based formulation results when both factors are one.

The mixing of node-based and element-based solutions for the node-based formulation is a stabilization technique to eliminate zero energy modes of a pure node-based formulation. With this in mind, two options are provided for the stress update of the element-based solution through the NODE BASED STABILIZATION METHOD command (applicable only with STRAIN INCREMENTATION = NODE_BASED). The default option, MATERIAL, runs the same material model in the element as is run at the nodes, with independent material states. The other option, EFFECTIVE_MODULI, uses a linearized update for the element stress state based on the element average value of the nodal effective moduli. The nodal effective moduli are computed from the nodal stress and strain increments at each time step. This second option avoids potential issues due to having independent node and element material states.

Node based elements store material state, stress, and strain data at the nodes in addition to at the element center. Most element based quantities such as stress have similarly named nodal equivalents.

If a node is attached to only elements of one material type that node will have one set of state, stress and strain data that is the average of the attached element quantities.

If elements of multiple materials are attached to the same node then that node will store multiple independent sets of state variables. To accommodate this the node based state data is given a unique name by appending a unique index number to the end of each state variable name.

The log file contains a table that defines the mapping from the index number the nodal element block. For example:

========NODAL BASED TETRAHEDRA ELEMENT BLOCK AND MATERIAL INFORMATION ==========

Block Nodal State Index

------- -----------------

block_1 1

block_7 2

block_200 3

================================================================================

Block 1, 7, and 200 are using nodal based tetrahedra element formulation. The nodal based stress in block 7 would be found in the nodal state variable stress_2. If a node was on a block boundary and attached to elements of block block 1 and block 7 then that node would have both stress_1, the stress associated with the block 1 material, and stress_2, the stress associated with the block 7 material. Note that for nodal based tetrahedra these nodal stresses and material states are the most relevant quantities to visualize. Additionally note that many derived output quantities such as the von Mises stress norm are not hooked to the nodal based output quantities.

The MASS LUMPING METHOD is used to set the algorithm for determination of the lumped nodal masses. The ROWSUM option means first compute the consistent mass matrix then set the lumped mass of each node as the sum of the consistent mass matrix row. The ROWSUM method gives more accurate gravity loads and a more consistently stable explicit time step. Row sum is the default method for most elements. The EVEN option means take the total element mass and divide it evenly between the elements nodes. The EVEN method exists mostly to allow backwards compatibility with previous Sierra/SM versions where the even mass lumping method was always used. The DEFAULT method means the code automatically picks the best mass lumping option based on element type. For most elements this is the row sum method. A few elements perform better with even mass lumping and use this method as the default.

Note that there also exist other solid element formulations which can be specified in the separate TOTAL LAGRANGE section block. These options are currently documented in the in development manual.

6.2.1.2. 10-Node Tetrahedron Default Formulation

The MEAN_QUADRATURE formulation has been deprecated for 10-node tetrahedron elements for robustness and accuracy reasons. The default formulation for the 10-node tetrahedron is the COMPOSITE_TET. This element can be used by creating an empty solid section, by not specifying a section in the block definition, or by using a Total Lagrange section. The default values for the COMPOSITE_TET are VOLUME AVERAGE J = ON and STRAIN_INCREMENTATION = STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE. See section Section 6.2.2 for more details.

6.2.2. Total Lagrange Section

Total Lagrangian [[4]] formulations are written in terms of Lagrangian measures of stress and strain, where derivatives are taken with respect to the Lagrangian or material coordinates. This differs from the approach used in most other element formulations in the code including the uniform gradient hex, which computes derivatives with respect to the Eulerian or spatial coordinates. The currently implemented finite element topologies for the total Lagrange section are the 8-noded hexahedron, 20-noded hexahedron, 27-noded hexahedron, 13-noded pyramid, 4-noded tetrahedron, 10-noded tetrahedron, and 15-noded wedge.

BEGIN TOTAL LAGRANGE SECTION <string>section_name

FORMULATION = <string>{FULLY_INTEGRATED|

COMPOSITE_TET}(FULLY_INTEGRATED)

STRAIN INCREMENTATION = <string>{STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE|

LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING}(STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE)

CUBATURE DEGREE = <integer>degree

VOLUME AVERAGE J = <string>{ON|OFF}

# VEM stabilization for tet10 elements

VEM STABILIZATION PARAMETER = <real>vem_shear_penalty(0.1)

VEM BULK STABILIZATION PARAMETER = <real>vem_bulk_penalty(1.0e-6)

VEM EXPONENT = <real>vem_exponent(5.0)

END [TOTAL LAGRANGE SECTION <string>section_name]

6.2.2.1. Formulation

FORMULATION = <string>{FULLY_INTEGRATED|

COMPOSITE_TET}(FULLY_INTEGRATED)

The FORMULATION command defaults to the FULLY_INTEGRATED formulation for the given finite element topology.

For the 10-noded tetrahedral topology, the COMPOSITE_TET option exists, which uses a piecewise linear nodal basis instead of the standard quadratic nodal basis. As stated in Reference [[5]], the element is classified as composite because conceptually it consists of 12 sub-elements, each of which is a linear, 4-noded tetrahedron. Thus, the basis functions used to represent nodal fields are piecewise linear within the element. The deformation gradient and stress fields are assumed to live in a linear space, and the resulting gradient operator incorporates the projection of the piecewise discontinuous gradients into the assumed linear basis. The current implementation does not restrict the mid-edge nodes to be co-linear with the vertex nodes, allowing for better geometric resolution for curved bodies.

6.2.2.2. Strain Incrementation

STRAIN INCREMENTATION = <string>{STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE|

LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING}(STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE)

In the total Lagrange formulation, the deformation gradient is always calculated as the derivative of the current configuration with respect to the reference configuration,

It follows that the incremental deformation gradient is defined as the deformation gradient between the configurations at times \(n\) and \(n+1\) and can be written in terms of \(\mathbf{F}_{n}\) and \(\mathbf{F}_{n+1}\),

The STRAIN INCREMENTATION command is then specific to hypoelastic material models, that is, models that use the rate of deformation to increment the stress. Two approaches are available: the STRONGLY_OBJECTIVE option in the context of the total Lagrange formulation mirrors what is found in the SOLID_SECTION as described in [[1]],

the LOGARITHMIC_MAPPING option is computationally more expensive, but comparatively more accurate in problems with large rotations,

6.2.2.3. Cubature Degree

CUBATURE DEGREE = <integer>degree

This option effectively determines the number of integration points to be employed during numerical integration. For hexahedral elements, CUBATURE DEGREE = 3 corresponds to 8 integration points, and for tetrahedral elements, CUBATURE DEGREE = 3 corresponds to 5 integration points. The default is CUBATURE DEGREE = 5 for the FULLY_INTEGRATED 27-noded hexahedron and CUBATURE DEGREE = 3 for all other FULLY_INTEGRATED formulation elements (note the COMPOSITE_TET formulation described below is fixed at CUBATURE DEGREE = 2 and may not be changed with this option).

The following topology, formulation, and cubature combinations are available:

ELEMENT FAMILY |

NUM. NODES |

FORMULATION |

CUBATURE DEGREE(S) |

|---|---|---|---|

hexahedron |

8 |

fully_integrated |

3 |

20 |

fully_integrated |

3 |

|

27 |

fully_integrated |

5 |

|

pyramid |

13 |

fully_integrated |

3 |

tetrahedron |

4 |

fully_integrated |

1, 2, 3 |

10 |

fully_integrated |

2, 3, 4 |

|

tetrahedron |

10 |

composite_tet |

2 |

wedge |

15 |

fully_integrated |

3 |

6.2.2.4. Volume Average J

VOLUME AVERAGE J = <string>{ON|OFF}

This command is used to construct a deformation gradient where the dilatational component is volume-averaged over the element domain. It is applicable for implicit and explicit problems employing nearly incompressible material response, such as metal plasticity, and may provide less stiff solutions in that case. In addition, if this command is ON, then the hydrostatic component of the stress is also volume averaged. The default setting is OFF for the FULLY_INTEGRATED formulation and ON for the COMPOSITE_TET formulation.

6.2.2.5. VEM Stabilization for 10-noded Tetrahedral Elements

VEM STABILIZATION PARAMETER = <real>vem_shear_penalty(0.1)

VEM BULK STABILIZATION PARAMETER = <real>vem_bulk_penalty(1.0e-6)

VEM EXPONENT = <real>vem_exponent(5.0)

The VOLUME AVERAGE J = ON option avoids pressure modes but sacrifices the coercivity of the system, which may lead to displacement instabilities. A stabilization inspired by the virtual element method [[6]] (VEM) is provided to suppress the displacement modes with the options VEM STABILIZATION PARAMETER = <real>vem_shear_penalty, VEM BULK STABILIZATION PARAMETER = <real>vem_bulk_penalty, and VEM EXPONENT = <real>vem_exponent. VEM STABILIZATION PARAMETER and VEM BULK STABILIZATION PARAMETER act like hourglass stiffnesses scaled by the shear and bulk moduli, respectively, and the VEM EXPONENT controls how quickly the stabilization stiffens under large dilitation within the element. These VEM command options are only activated for fully-integrated and composite tet10 elements with CUBATURE DEGREE = 2 and VOLUME AVERAGE J = ON. The defaults are generally recommended but the optimal values can be problem dependent, so each can be set at the user’s discretion.

6.2.3. Cohesive Section

BEGIN COHESIVE SECTION <string>cohesive_section_name

FORMULATION = <string>FULLY_INTEGRATED|UNDER_INTEGRATED(FULLY_INTEGRATED)

LAYER THICKNESS = <real>layer_thickness(0.0)

END [COHESIVE SECTION <string>cohesive_section_name]

Warning

In order for the cohesive elements to contribute to the global stable time step, a node based time step must be used. See Section 3.2.3 for details.

The COHESIVE SECTION command block specifies the properties for cohesive zone elements (quadrilateral and triangular). The name of this block (given by cohesive_section_name) is referenced by the element block for cohesive elements. If the option for adaptive insertion of cohesive zone elements is used, the name of this block is referenced by the COHESIVE SECTION command defined in Section 6.5.7.

FORMULATION specifies the number of integration points for the cohesive element. The default is to fully integrate the element, which means the larger of the two possible number of integration points is used. It should be noted that with a single integration point (or under-integrating the element in general), spurious hourglass-like modes may be introduced to the deformation of the cohesive element. Therefore it is recommended to keep the default full integration schemes. Currently, the quadrilateral cohesive element supports either one or four integration points, the triangular cohesive element supports either one or three integration points, and the composite triangular cohesive element supports either four or twelve integration points.

The LAYER THICKNESS specifies the thickness to use for determining the mass of the cohesive element layer. A cohesive element is formulated as a surface element which implies that there is no volume to the element. Specifying a layer thickness allows the cohesive element to remain a surface element but have mass. This option is especially useful for cohesive elements that are meshed independently and tied to the remaining mesh with MPCs. Mass is required for motion to occur in dynamics. The element wise mass element_mass will be the cse_initial_area multiplied by the LAYER_THICKNESS and the DENSITY specified in the cohesive material model.

Warning

LAYER_THICKNESS is not supported with shell and wedge cohesive elements.

6.2.4. Localization Section

BEGIN LOCALIZATION SECTION <string>localization_section_name

MEAN DILATATION FORMULATION

NUMBER OF INTEGRATION POINTS = <integer>num_int_points

THICKNESS = <real>thickness

MEMBRANE FORCES = ON | OFF (ON)

END [LOCALIZATION SECTION <string>localization_section_name]

Warning

Currently the localization elements do not contribute to the global stable time step. As such, the user must specify a time step via the INITIAL TIME STEP and TIME STEP INCREASE FACTOR command lines. See Section 3.1 for details.

6.2.4.1. Kinematics

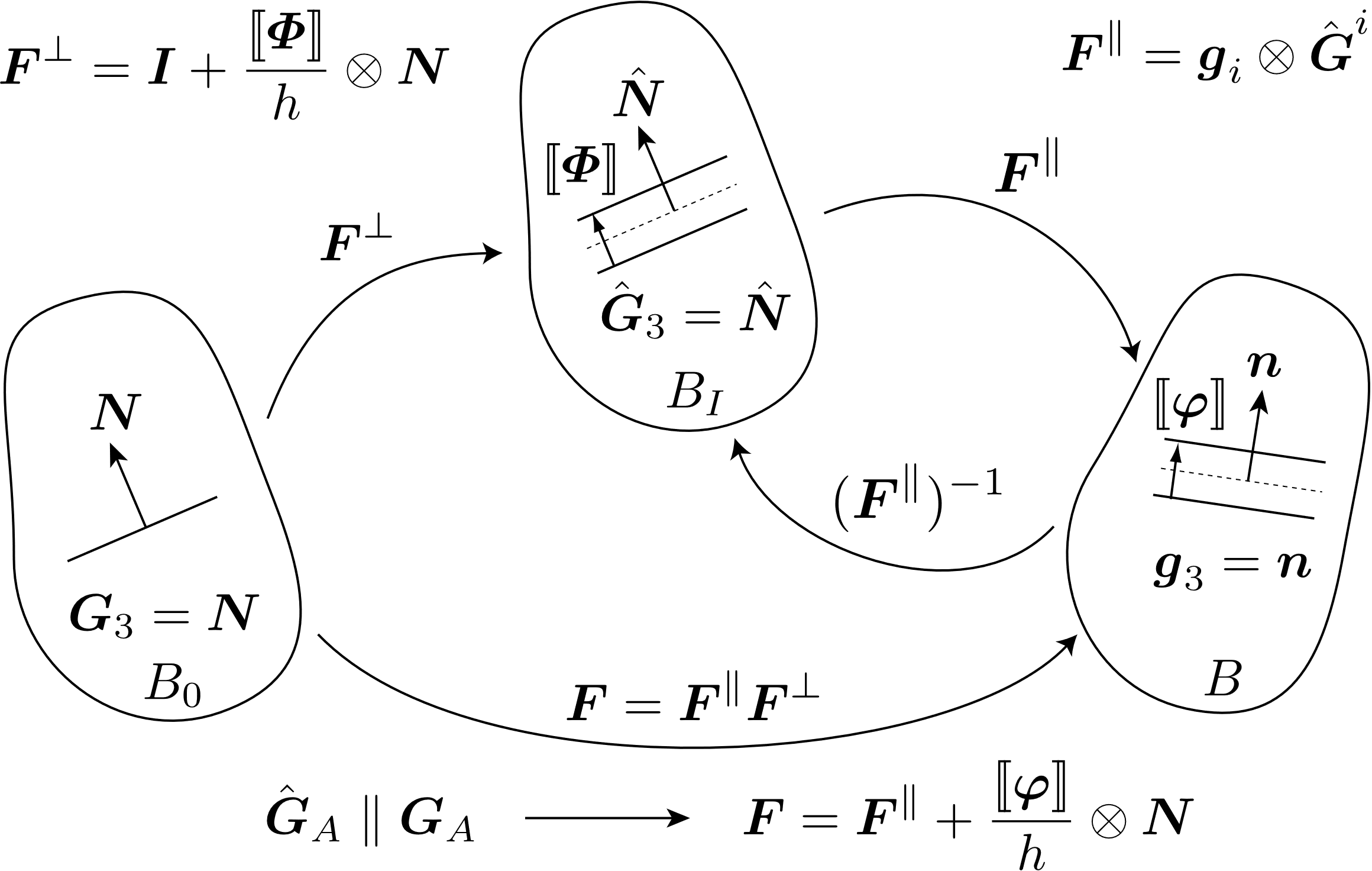

Localization elements [[7]] are planar elements that lie between bulk (volumetric) elements and can employ the same underlying bulk material model. Topologically, localization elements are identical to cohesive surface elements. The reason this 2D surface element can access 3D material models is due to the multiplicative decomposition of the deformation gradient \(\mathbf{F}\) such that \(\mathbf{F} = \mathbf{F}^{\parallel} \mathbf{F}^{\perp}\). Each portion of the decomposition can be expressed as

where \(\mathbf{F}^{\parallel}\) encapsulates in-plane stretching and \(\mathbf{F}^{\perp}\) reflects the displacement jump \(\lbrack\!\lbrack \mathbf{\varPhi} \rbrack\!\rbrack\) in the intermediate configuration which can be pushed to the current configuration through \(\lbrack\!\lbrack \mathbf{\varphi} \rbrack\!\rbrack = \mathbf{F}^{\parallel} \lbrack\!\lbrack \mathbf{\varPhi} \rbrack\!\rbrack\). Fig. 6.2 illustrates the kinematic construction.

Fig. 6.2 The reference \(B_{0}\), intermediate \(B_{I}\), and current configuration \(B\) of the body. By redefining the jump in the intermediate configuration, the formulation simplifies to an additive decomposition having contributions from membrane stretching and the jump.

The jump is normalized by \(h\) which one can envision as an element thickness or a characteristic length scale governing separation. Quantities are considered to be constant through the thickness \(h\). The curvilinear basis vectors in the reference and current configuration are \(\mathbf{G}_{A}\) and \(\mathbf{g}_{i}\), respectively. Given that \(\mathbf{N}\) is constructed to be normal to the in-plane basis vectors \(\mathbf{G}_{A}\) in the reference configuration, one can prove that the in-plane basis vectors in the intermediate configuration are equivalent to the in-plane basis vectors in the reference configuration (\(\hat{\mathbf{G}}_{A} = \mathbf{F}^{\perp} \mathbf{G}_{A} = \mathbf{G}_{A}\)). One can then express the multiplicative decomposition as an additive decomposition thus simplifying the initial formulation given in [[7]].

Because the length scale \(h\) is independent of the discretization, the methodology is regularized and ideal for employing a local, softening material model to simulate the failure process. Details concerning the force calculation are available in [[7]].

6.2.4.2. Command summary

The LOCALIZATION SECTION command block specifies the properties for localization elements (quadrilateral and triangular). The name of this block (given by localization_section_name) is referenced by the element block for localization elements.

MEAN DILATATION FORMULATION

This command line will yield a constant pressure formulation. The average pressure is obtained at all integration points through a modification of the kinematic quantities. For hypo-elastic materials, \(\text{tr}[\mathbf{D}]\) is volume-averaged. For uncoupled hyperelastic models, \(\text{det}[\mathbf{F}]\) is volume-averaged. After volume averaging \(\text{tr}[\mathbf{D}]\) and \(\text{det}[\mathbf{F}]\), local dilatational contributions are removed, and additively (hypoelastic) or multiplicatively (hyperelastic) include the volume-averaged response. This results in an average pressure (by construction) and has been shown to be effective in avoiding element locking during isochoric deformations. Note that one can use a single integration point to achieve a constant pressure, but hourglass control is not provided to suppress spurious modes. If isochoric deformations are of concern, it is recommended to use a fully-integrated element with the MEAN DILATATION FORMULATION. The MEAN DILATATION FORMULATION will only be applied if the command is given in the LOCALIZATION SECTION.

NUMBER OF INTEGRATION POINTS = <integer>num_int_points

The default number of integration points for a localization element depends on the topology, but is always sufficient for full integration. For an eight-noded hexahedron (planar four-noded quadrilateral) the default is four integration points while for a six-noded wedge (planar three-noded triangle) the default is one integration point. However, it should be noted that with a single integration point, spurious hourglass modes can be introduced into the deformation of the quadrilateral localization element. Currently, the quadrilateral localization element supports one and four integration points while the triangular localization element supports one integration point.

THICKNESS = <real>thickness

The THICKNESS command line sets the localization element thickness \(h\). In many respects, \(h\) should be considered a material parameter as it governs the evolution of surface separation. The introduction of \(h\) generates the true length scale in the problem: the process zone size. Care must be taken to adequately resolve the process zone size or the methodology will not be regularized.

MEMBRANE FORCES = ON | OFF (ON)

The MEMBRANE FORCES command line should be used when the element size \(l\) is on the order of \(h\). In this specific case, the membrane forces will be sufficiently large to corrupt the crack-tip fields. If \(h \sim l\), we recommend that the membrane forces be OFF. Turning off membrane forces alters the force calculation to only employ the referential traction \(\mathbf{T} = \mathbf{P}\mathbf{N}\). In this sense, the formulation becomes “cohesive.” But because \(\mathbf{F}^{\parallel}\) is still employed in the kinematics to capture critical quantities such as the triaxiality, the stiffness matrix is no longer symmetric; however, the residual is correct. Numerous studies in implicit quasi-statics and implicit dynamics have confirmed that CG is still robust. To avoid non-monotonic reductions in the residual, one might employ solvers that can handle non-symmetric systems (ML) and solution methods other than CG (Newton with a line search) to obtain improved rates of convergence.

Warning

Domain decomposition may generate domains in which localization elements are isolated. Neither the upper or lower surface is connected to a bulk element. Because the localization element does contain a zero-energy membrane mode that is suppressed through bulk element assembly, the user will receive warnings that indicate additional rigid body modes on particular processors. To remedy the issue, the user can employ tangent diagonal scaling in the preconditioner. Studies have show this solution to be effective with minimal impact on the rate of convergence.

6.2.4.3. Usage guidelines

In contrast to cohesive surface elements, localization elements can employ bulk constitutive models for surface separation. For a typical application, the analyst might

Identify a constitutive model that captures the failure process. This might include a local damage model or any model that employs strain softening to facilitate strain localization.

Conduct mesh-dependent simulations with bulk elements of size \(s\) to understand potential paths for crack initiation and growth in specimen geometries targeted for parameterizing constitutive model parameters.

Seed potential paths in specimen geometries and incorporate \(h\) into the fitting process. The fitting process may not be unique in that the same far-field response might be obtained from multiple combinations of both \(h\) and the material parameters that govern the failure process. An initial guess to being the iterative process might include \(h = 1/4 s\). Ensure that for all cases of \(h\) that the process zone that evolves is resolved.

Consider the possibility of only enabling strain softening in the constitutive model that drives surface separation. Although this will assure that localization will occur in the surface elements, regulating softening to the seeded plane can introduce non-smoothness in the failure process.

Understand the impact of \(h\). If \(h\) is too large, the fields governing the failure process will be less smooth and the additional compliance can create additional nonlinearities that can complicate implicit solution. Please consider refitting model parameters with lower values of \(h\). If \(h\) is too small, the localization element thickness will drive the condition number of the implicit system.

Explore component or system level geometries with seeded paths for crack initiation and propagation. Additional simulations with bulk elements may be conducted to highlight potential failure paths. Refine the mesh to ensure that the far-field predictions are indeed mesh independent and that the process zone that evolves from the given micromechanics regularized by the length scale \(h\) is resolved.

Inspect of the process zone with a focus on the local metrics that drive the failure process. For example, if stress triaxiality drives void growth, one should examine fields of triaxiality in both the bulk and localization elements. In contrast to other methods like the \(J\)-integral that focus on a driving force evaluated at some radius from the crack tip, localization elements seek to capture the resistance at the crack tip. Consequently, crack-tip fields must be resolved.

Reflect on the fields employed for model parameterization and the fields evolving in component and system level models. If possible, align field evolution in component/system geometries with field evolution in specimen geometries. Disparities may drive the need for additional calibration experiments.

Although these usage guidelines have not focused on incorporating stochastic processes, one may sample distributions in material parameters. The inclusion of a method for regularization enables such findings in that the mesh-dependence associated with fracture/failure is not convoluted with a stochastic representation of the micro-mechanical process.

6.2.5. Shell Section

BEGIN SHELL SECTION <string>shell_section_name

THICKNESS = <real>shell_thickness

THICKNESS MESH VARIABLE =

<string>THICKNESS|<string>var_name

THICKNESS TIME STEP = <real>time_value

THICKNESS SCALE FACTOR = <real>thick_scale_factor(1.0)

CONTACT THICKNESS SCALE FACTOR = <real>thick_scale_factor(thick_scale_factor)

INTEGRATION RULE = TRAPEZOID|GAUSS|LOBATTO|SIMPSONS|

USER|ANALYTIC|CODE_SELECTED(CODE_SELECTED)

NUMBER OF INTEGRATION POINTS = <integer>num_int_points(5)

FORMULATION = KH_SHELL|BT_SHELL|BL_SHELL|NQUAD|

C0_TRI_SHELL|ORIG_TRI_SHELL (BT_SHELL"QUAD" or ORIG_TRI_SHELL"Tri")

RIGID BODY PROJECTOR =

NONE|DRILLING_ONLY|ROTATIONS_AND_DRILLING (ROTATIONS_AND_DRILLING)

BEGIN USER INTEGRATION RULE

<real>location_1 <real>weight_1

<real>location_2 <real>weight_2

.

.

<real>location_n <real>weight_n

END [USER INTEGRATION RULE]

LOFTING FACTOR = <real>lofting_factor(0.5)

LOFTING FACTOR MESH VARIABLE = <string>var_name

OFFSET MESH VARIABLE = <string>var_name

ORIENTATION = <string>orientation_name

DRILLING STIFFNESS FACTOR = <real>stiffness_factor(1.0e-5)

RIGID BODY = <string>rigid_body_name

RIGID BODIES FROM ATTRIBUTES = <integer>first_id

TO <integer>last_id

STABLE TIME STEP ESTIMATE = COURANT|GERSCHGORIN(GERSCHGORIN)  CONTACT THICKNESS = <real>contactThickness

CONTACT LOFTING FACTOR = <real>contactLofting

FIBER ORIENTATION = <real>angle(0)

R VECTOR READ VARIABLE = <string>rVecName

T VECTOR READ VARIABLE = <string>tVecName

END [SHELL SECTION <string>shell_section_name]

CONTACT THICKNESS = <real>contactThickness

CONTACT LOFTING FACTOR = <real>contactLofting

FIBER ORIENTATION = <real>angle(0)

R VECTOR READ VARIABLE = <string>rVecName

T VECTOR READ VARIABLE = <string>tVecName

END [SHELL SECTION <string>shell_section_name]

The SHELL SECTION command block specifies the properties for a shell element. If this command block is referenced in an element block of three-dimensional, four-node elements, the elements in the block will be treated as shell elements. The parameter, shell_section_name, is user-defined and is referenced by a SECTION command line in a PARAMETERS FOR BLOCK command block.

Either a THICKNESS command line or a THICKNESS MESH VARIABLE command line must appear in the SHELL SECTION command block.

If a shell element block references a SHELL SECTION command block with

the command line:

THICKNESS = <real>shell_thickness

then the thickness of all shell elements in the block will be initialized to the value shell_thickness.

Sierra/SM can also initialize the thickness using an attribute defined on elements in the mesh file. Meshing programs such as PATRAN and Cubit typically set the element thickness as an attribute on the elements. If the elements have one and only one attribute defined on the mesh, the THICKNESS MESH VARIABLE command line should be specified as

THICKNESS MESH VARIABLE = THICKNESS

which causes the thickness of the element to be initialized to the value of the attribute for that element. If there are zero attributes or more than one attribute, the thickness variable will not be automatically defined, and the command will fail.

The thickness may also be initialized by a scalar element field on the input mesh. To specify a field other than the single-element attribute, use the following form of the THICKNESS MESH VARIABLE command line:

THICKNESS MESH VARIABLE = <string>var_name

Here, the string var_name is the name of the initializing element field.

The input mesh may have values defined at more than one point in time. To choose the point in time in the mesh file that the variable should be read, use the command line

THICKNESS TIME STEP = <real>time_value

The default time point in the mesh file at which the variable is read is 0.0.

Once the thickness of a shell element is initialized by using either the THICKNESS command line or the THICKNESS MESH VARIABLE command line, this initial thickness value can then be scaled using the scale-factor command line:

THICKNESS SCALE FACTOR = <real>thick_scale_factor

If the initial thickness of the shell is 0.15 inch, and the value for thick_scale_factor is 0.5, then the scaled thickness of the membrane will be 0.075.

The thickness mesh variable specification may be coupled with the THICKNESS SCALE FACTOR command line. In this case, the thickness mesh variable is scaled by the specified factor.

CONTACT THICKNESS SCALE FACTOR = <real>contact_thick_scale_factor

The CONTACT THICKNESS SCALE FACTOR command is used for overwriting the value of THICKNESS SCALE FACTOR for contact purposes.

If the initial thickness of the shell is 0.15 inch, the value of thick_scale_factor is 0.5, and the value of contact_thick_scale_factor is 1.0, then the shell contact thickness will be equal to the original thickness (0.15) inches.

The thickness mesh variable specification may be coupled with the CONTACT THICKNESS SCALE FACTOR command line. In this case, the thickness mesh variable is scaled by the specified factor for contact.

The shell formulation can be selected via the FORMULATION command line. Several options are available:

The

BT_SHELLoption is used to select the Belytschko-Tsay (BT) shell formulation. This is the default. The BT shell formulation has constant transverse shear, and is the fastest shell element available. Note, this element can experience stability issues at large in-plane strains.The

BL_SHELLoption is used to select the Belytschko-Leviathan (BL) shell formulation. The BL shell element is similar to the Belytschko-Tsay element but has additional shear terms and hourglass controls that the BT does not have. It also includes a projection of the angular velocities and the internal forces. The BL can better solve problems with high gradients of transverse shear (such as twisted beams), and no hourglass control or drilling stiffness is needed. Note, this element can experience stability issues at large in-plane strains.The

KH_SHELLoption specifies the Key-Hoff shell formulation, which includes a nonlinear transverse shear term. The Key-Hoff shell can better solve problems with high gradients of transverse shear (such as twisted beams), but distorted (non-rectangular) elements can be excessively stiff. Note, this element can experience stability issues at large in-plane strains.The

NQUADoption selects a formulation for a completely elastic plate.The

C0_TRI_SHELLoption specifies the triangular shell formulation developed by Kennedy, Belytschko, and Lin (1986). The \(C^{0}\) tri shell is a robust, versatile element that uses an incremental strain computation, making it applicable to large strains. Note that this element has no resistance to rotations about the axis perpendicular to its plane.The

TRI_SHELLoption is a specialized triangular shell formulation. The option is in development and generally should not be used in production runs.

For the Belytschko-Leviathan shell formulation (BL_SHELL), the user may specify which rigid body modes to project out of the local velocity and force vectors via the RIGID BODY PROJECTOR command. The options are NONE, DRILLING_ONLY, and ROTATIONS_AND_DRILLING (the default). The NONE option indicates no rigid body modes are projected out and is only recommended for explicit analyses with relatively flat geometry. The DRILLING_ONLY option removes modes associated with the drilling degrees of freedom which are unconstrained in the 5-DoF family of shell elements. The ROTATIONS_AND_DRILLING option is a full projection that removes rigid body rotations and the drilling modes and is appropriate if warped shells are present. The last option also preserves angular momentum but leads to a stiffer response for the BL shell [[8], [9]].

Warning

The RIGID BODY PROJECTOR command is currently only available for the Belytschko-Leviathan shell formulation. The use of this command with other shell formulations has no effect.

For shell elements, the user may select from a number of integration rules, including a user-defined integration option. The integration rule is selected with the command line

INTEGRATION RULE = <string>TRAPEZOID|GAUSS|LOBATTO|SIMPSONS|

ANALYTIC|CODE_SELECTED|USER(CODE_SELECTED)

Consult the element documentation [[2]] for a description of different integration schemes for shell elements.

For most material models the code will by default select the five point TRAPEZOID through the thickness integration rule. The code selected integration scheme for the elastic material model is ANALYTIC, which is an analytic through-thickness integration scheme. This scheme is significantly faster and slightly more accurate than any of the point-wise rules but only valid for fully elastic shell formulations.

Currently the analytic integration scheme is only available for the elastic material model when using the BT_SHELL and BL_SHELL shell formulations for quad shell elements.

Shells using the analytic integration rule do not compute integration point material or stress quantities such as stress, strain, or the various quantities derived from stress and strain. If integration point quantities are desired for elastic material shells, the shells can be forced to use a point-wise integration scheme by manually setting the integration rule to TRAPEZOID or another point-wise rule.

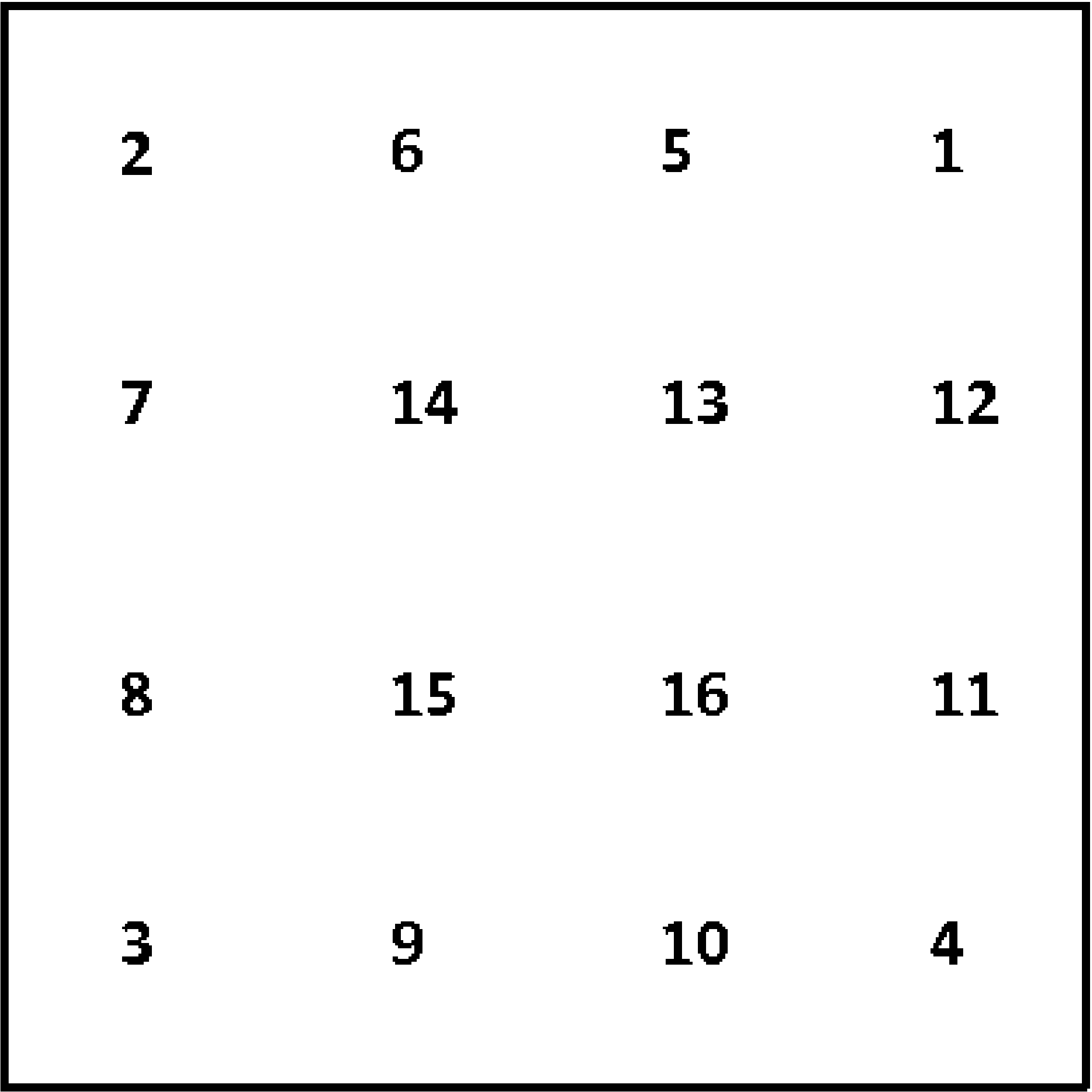

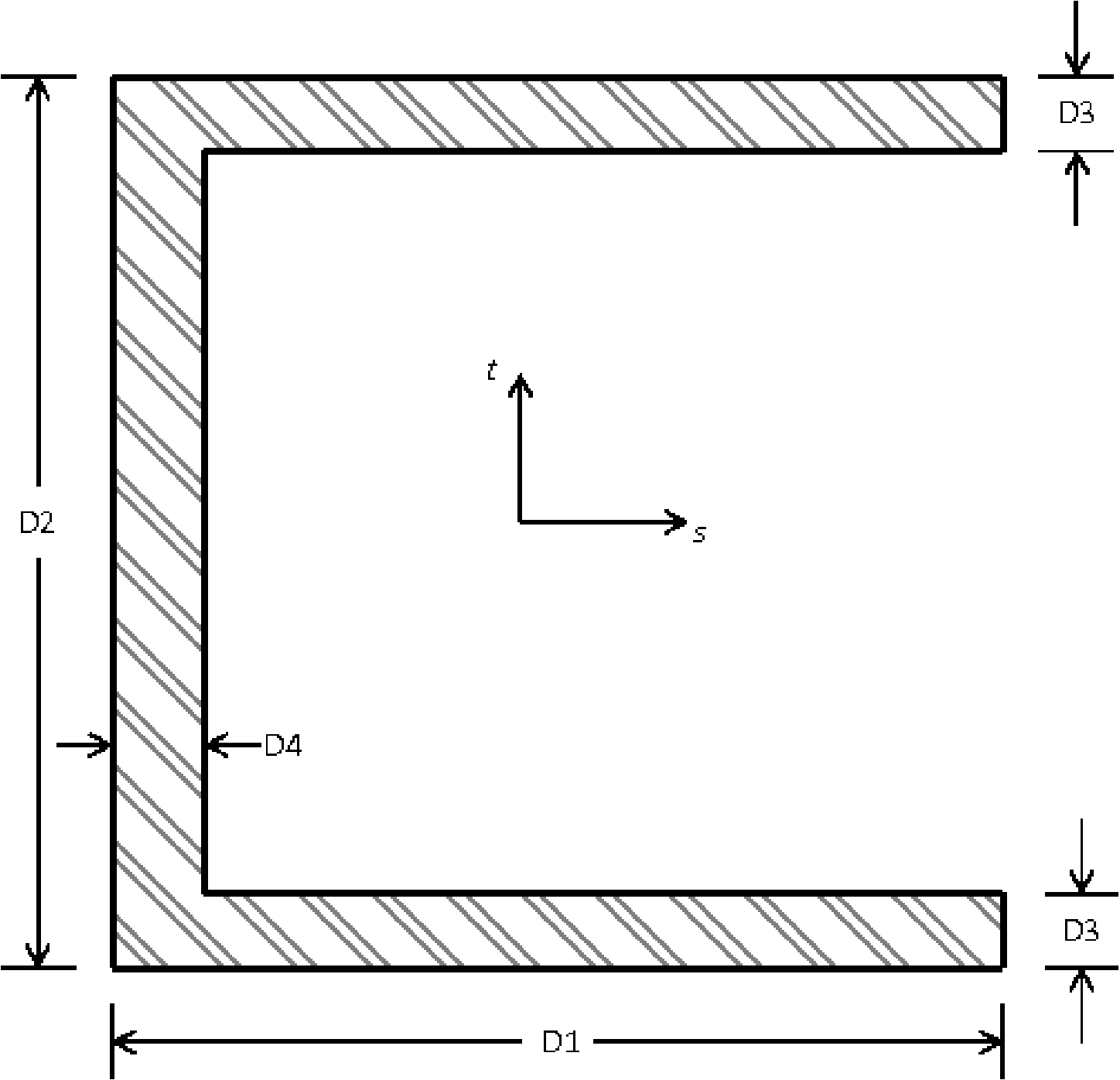

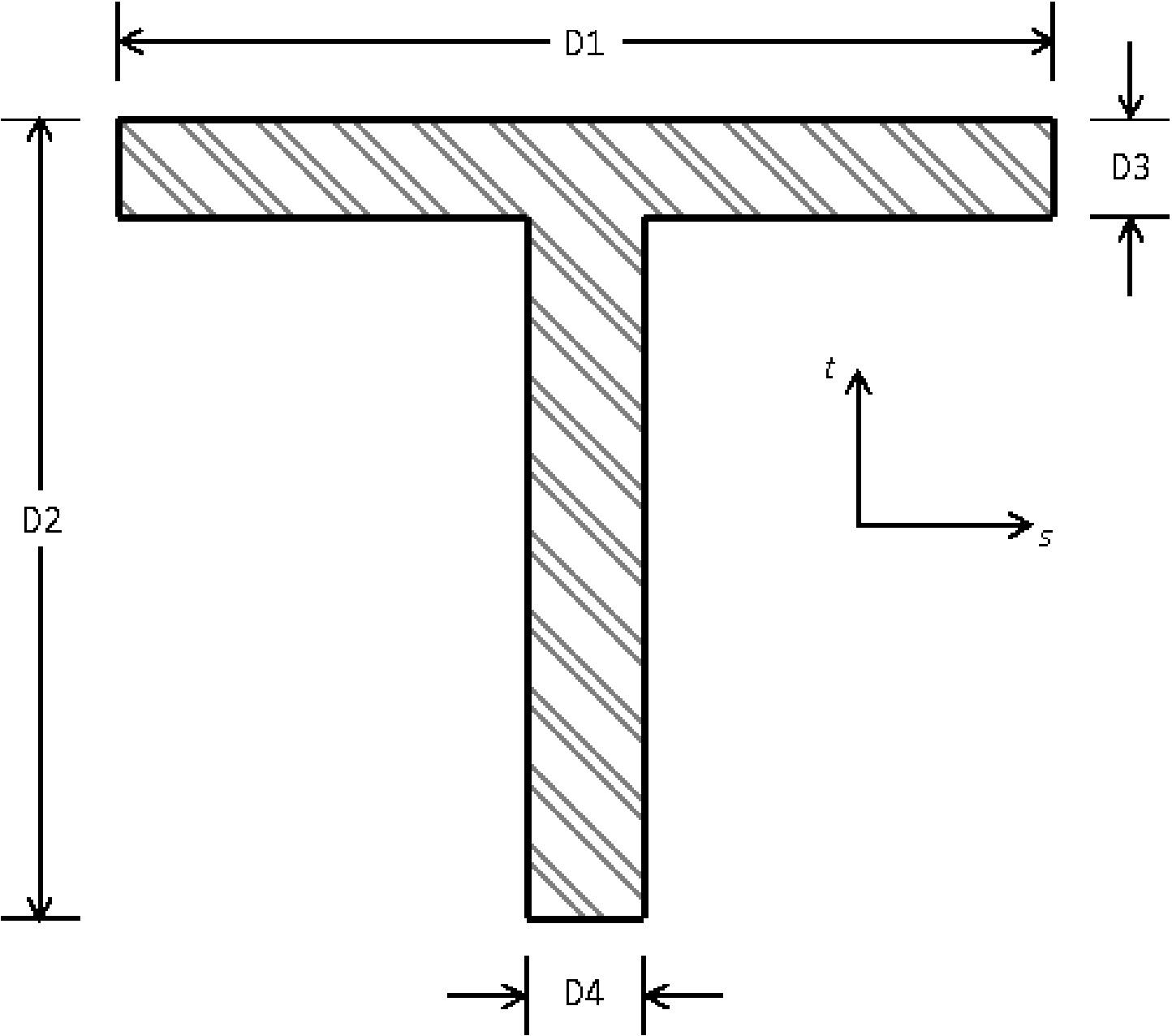

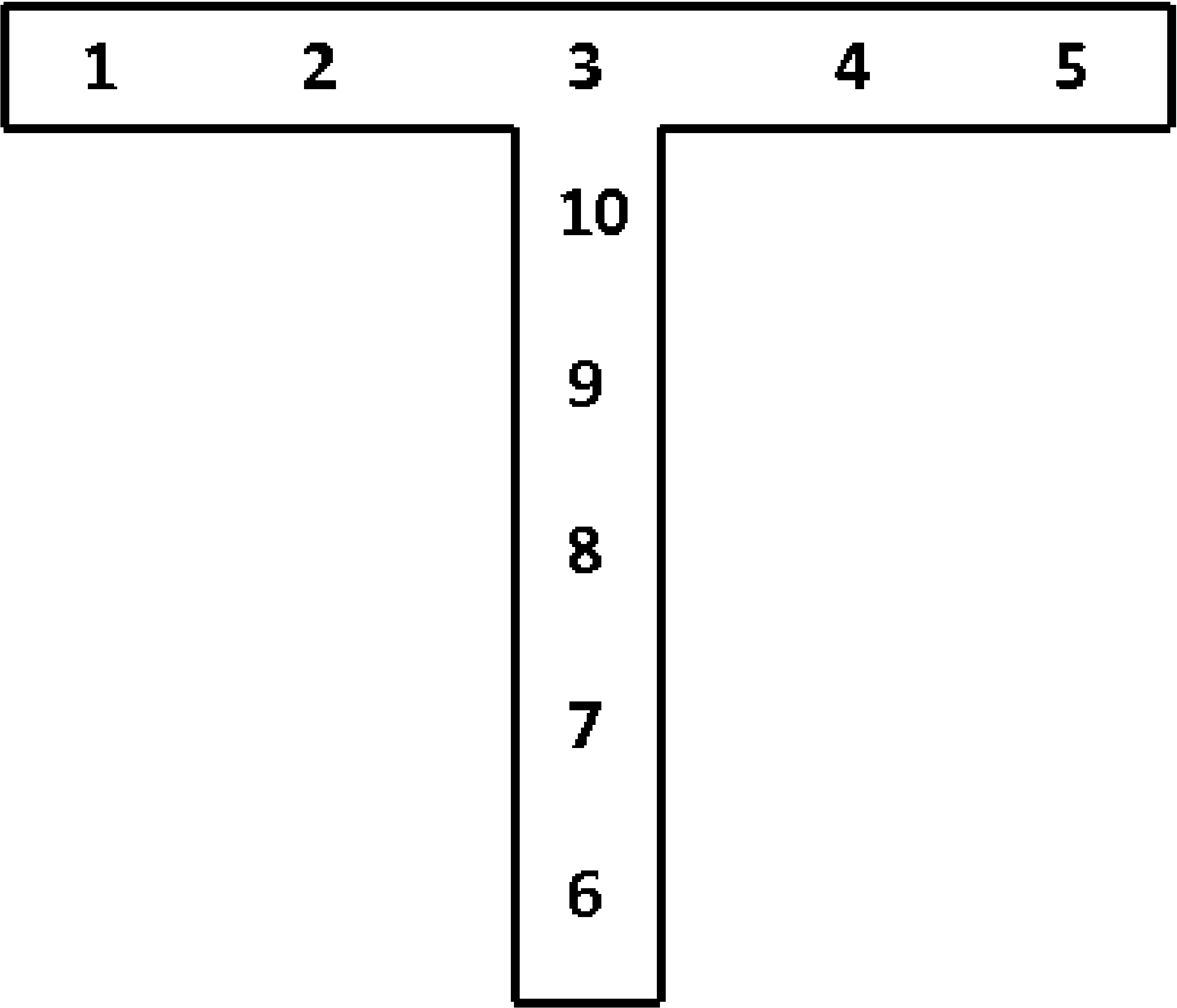

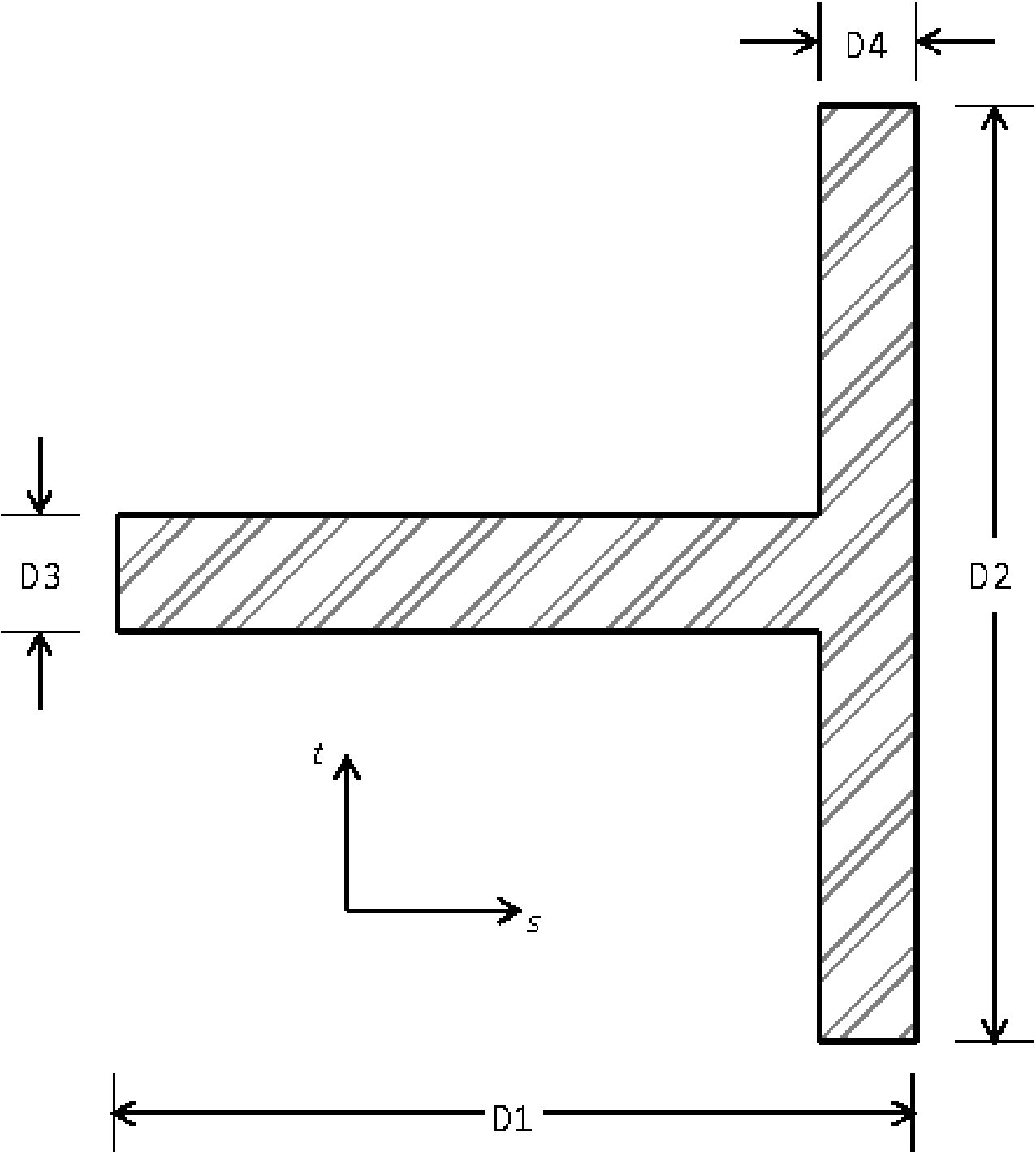

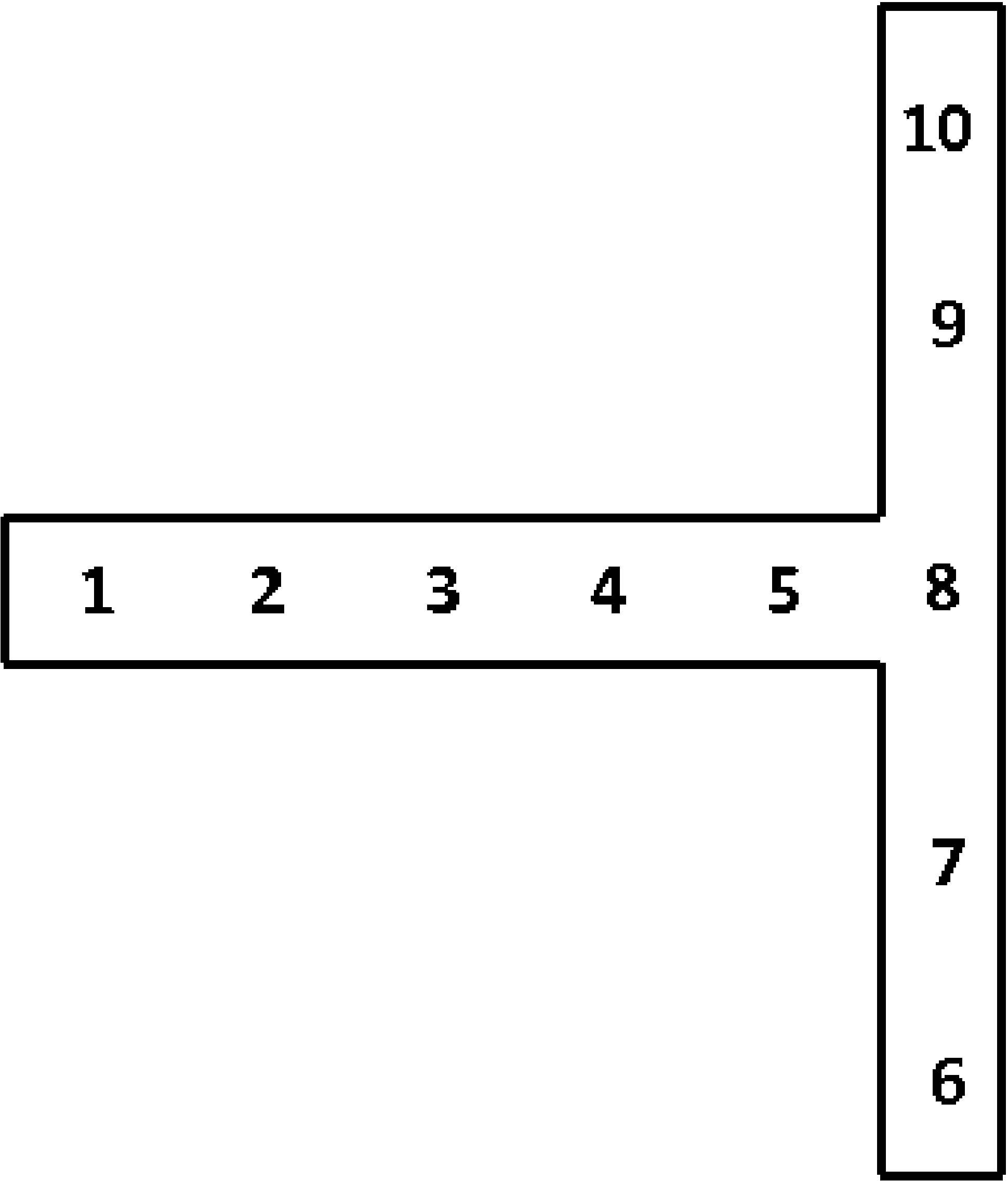

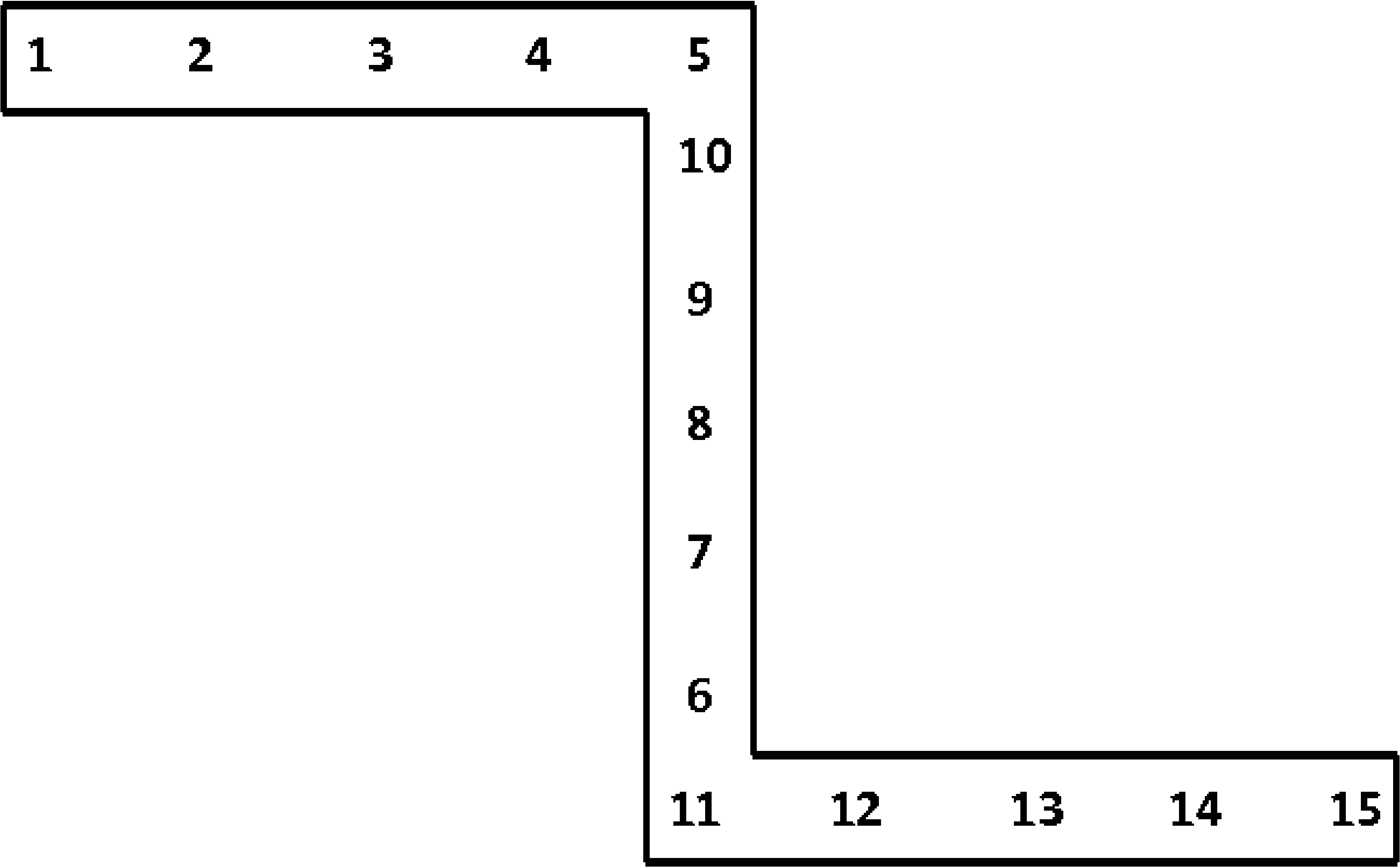

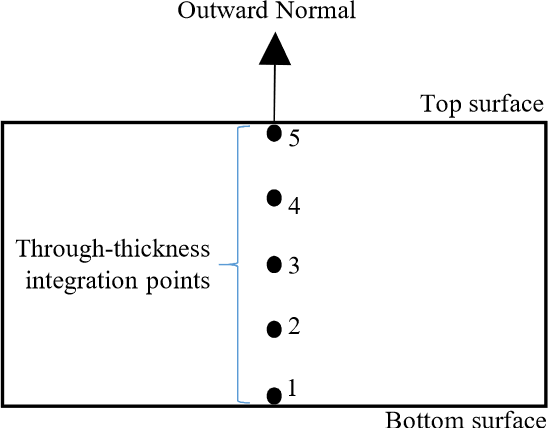

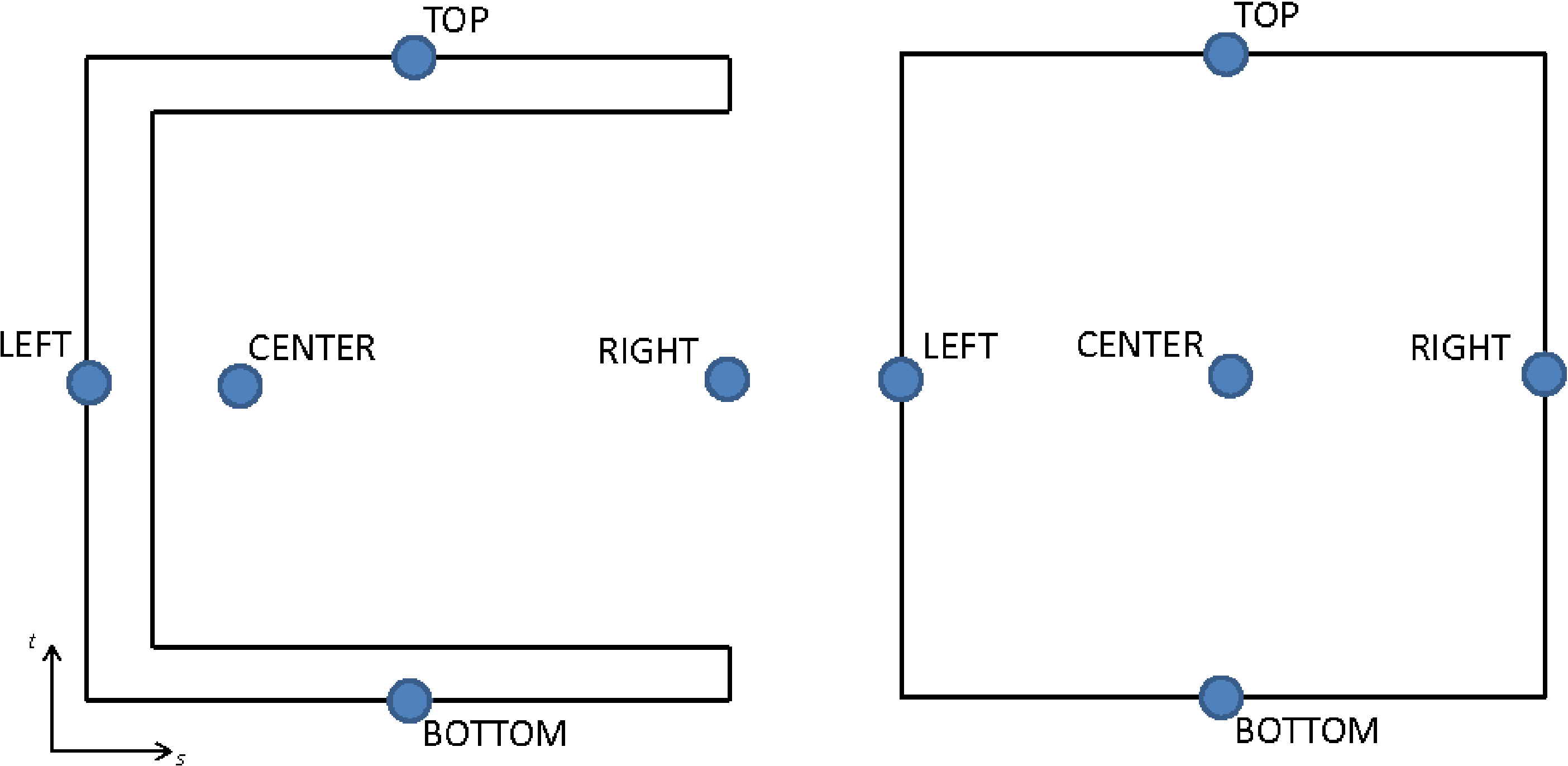

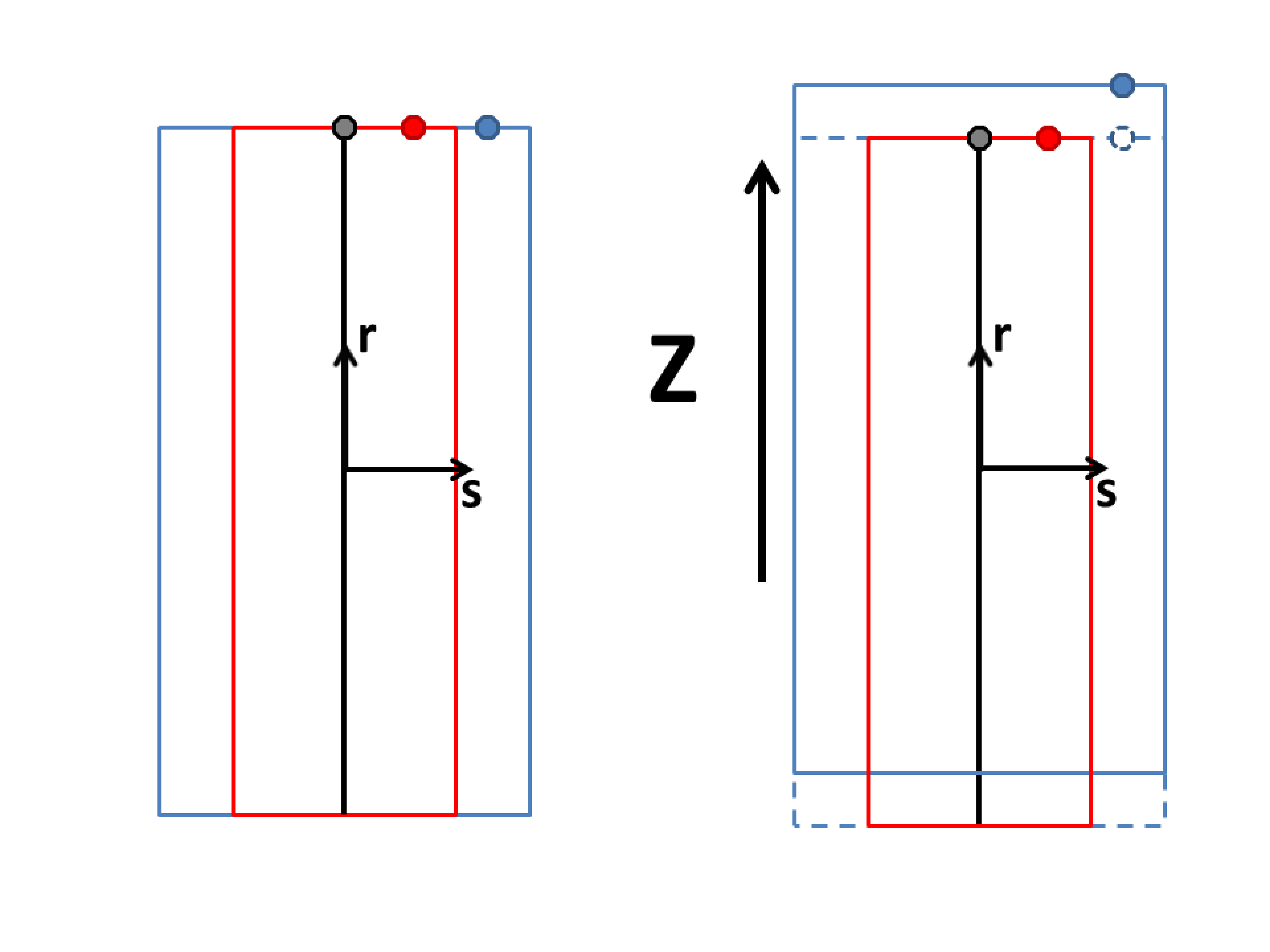

For all integration schemes, the through-thickness integration points are indexed starting at the point closest to the bottom surface with respect to the positive normal direction (See Fig. 6.3). For example, when requesting unrotated_stress_xx for a shell element using 5 integration points through the thickness, unrotated_stress_xx_1 corresponds to the integration point closest to the bottom surface and unrotated_stress_xx_5 corresponds to the integration point closest to the top surface.

Fig. 6.3 Indexing convention for through-thickness integration points.

The number of integration points for the piecewise integration point rules can be set to any number greater than one by using the following command line:

NUMBER OF INTEGRATION POINTS = <integer>num_int_points(5)

The SIMPSONS, GAUSS, and LOBATTO integration schemes in the INTEGRATION RULE command line all default to five integration points. The number of integration points for these three schemes can be reset by using the NUMBER OF INTEGRATION POINTS command line. There are limitations on the number of integration points for some of these integration rules. The SIMPSONS rule can be set to any number greater than one, the GAUSS scheme can be set to one through seven integration points, and the LOBATTO integration scheme can be set to two through seven integration points.

In addition to these standard integration schemes, the USER INTEGRATION RULE command block may be used to define a custom integration scheme.

BEGIN USER INTEGRATION RULE

<real>location_1 <real>weight_1

<real>location_2 <real>weight_2

.

.

<real>location_n <real>weight_n

END [USER INTEGRATION RULE]

A standard integration scheme and a user scheme may not be specified simultaneously. If the USER option is specified in the INTEGRATION RULE command line, a set of integration locations with associated weight factors must be specified. This is done with tabular input command lines inside the USER INTEGRATION RULE command block. The number of command lines inside this command block should match the number of integration points specified in the NUMBER OF INTEGRATION POINTS command line. For example, to use a user-defined scheme with three integration points, the NUMBER OF INTEGRATION POINTS command line should specify three (3) integration points and the number of command lines inside the USER INTEGRATION RULE command block should be three (to give three locations and three weight factors).

For the user-defined rule, the integration point locations should fall between \(-1.0\) and \(1.0\), and the weights should sum to \(2.0\).

The command line

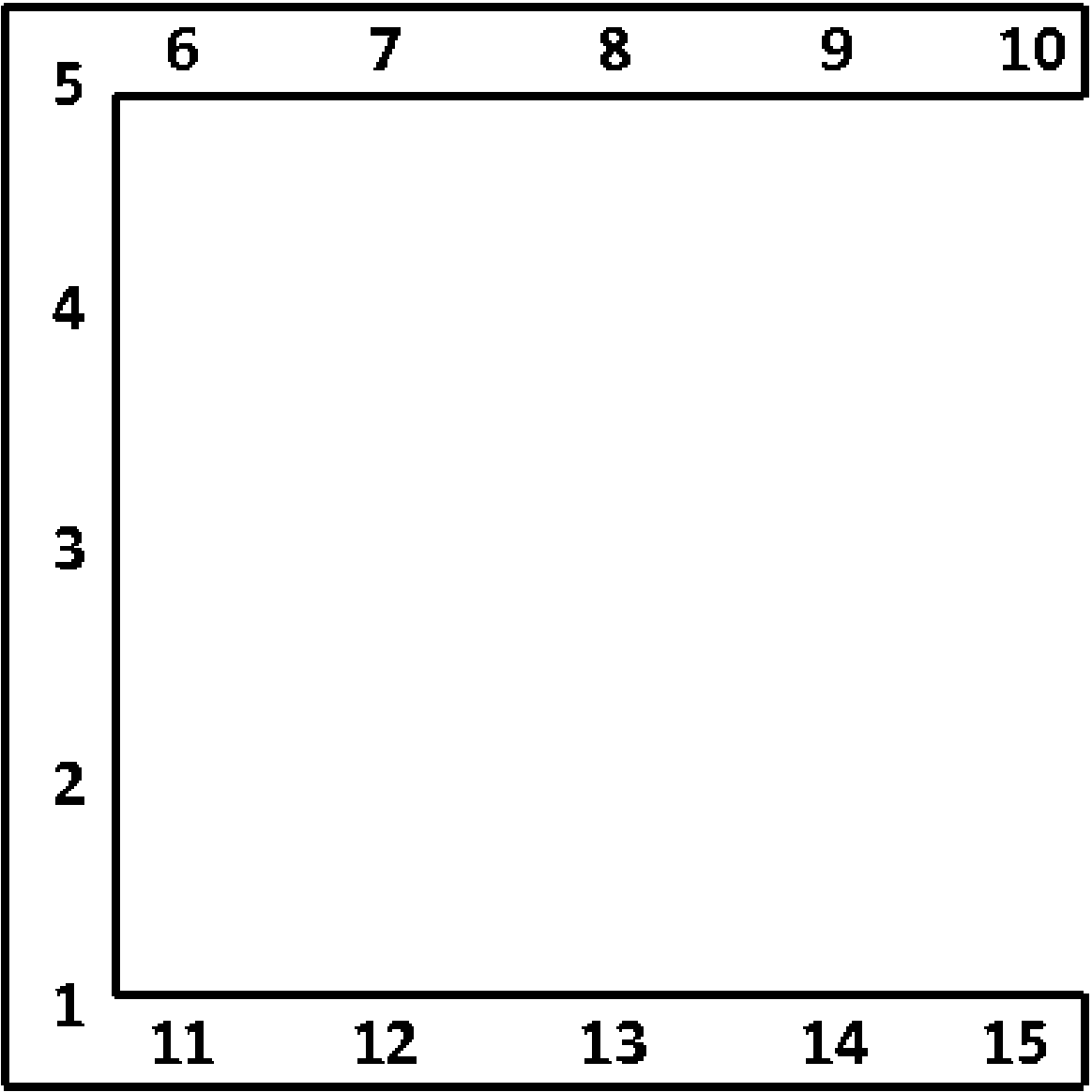

LOFTING FACTOR = <real>lofting_factor(0.5)

allows the user to shift the location of the mid-surface of a shell element relative to the geometric location of the shell element. By default, the geometric location of a shell element in a mesh represents the mid-surface of the shell. If a shell has a thickness of 0.2 inch, the top surface of the shell is 0.1 inch above the geometric surface defined by the shell element, and the bottom surface of the shell is 0.1 inch below the geometric surface defined by the shell element. (The top surface of the shell is the surface with a positive element normal; the bottom surface of the shell is the surface with a negative element normal.)

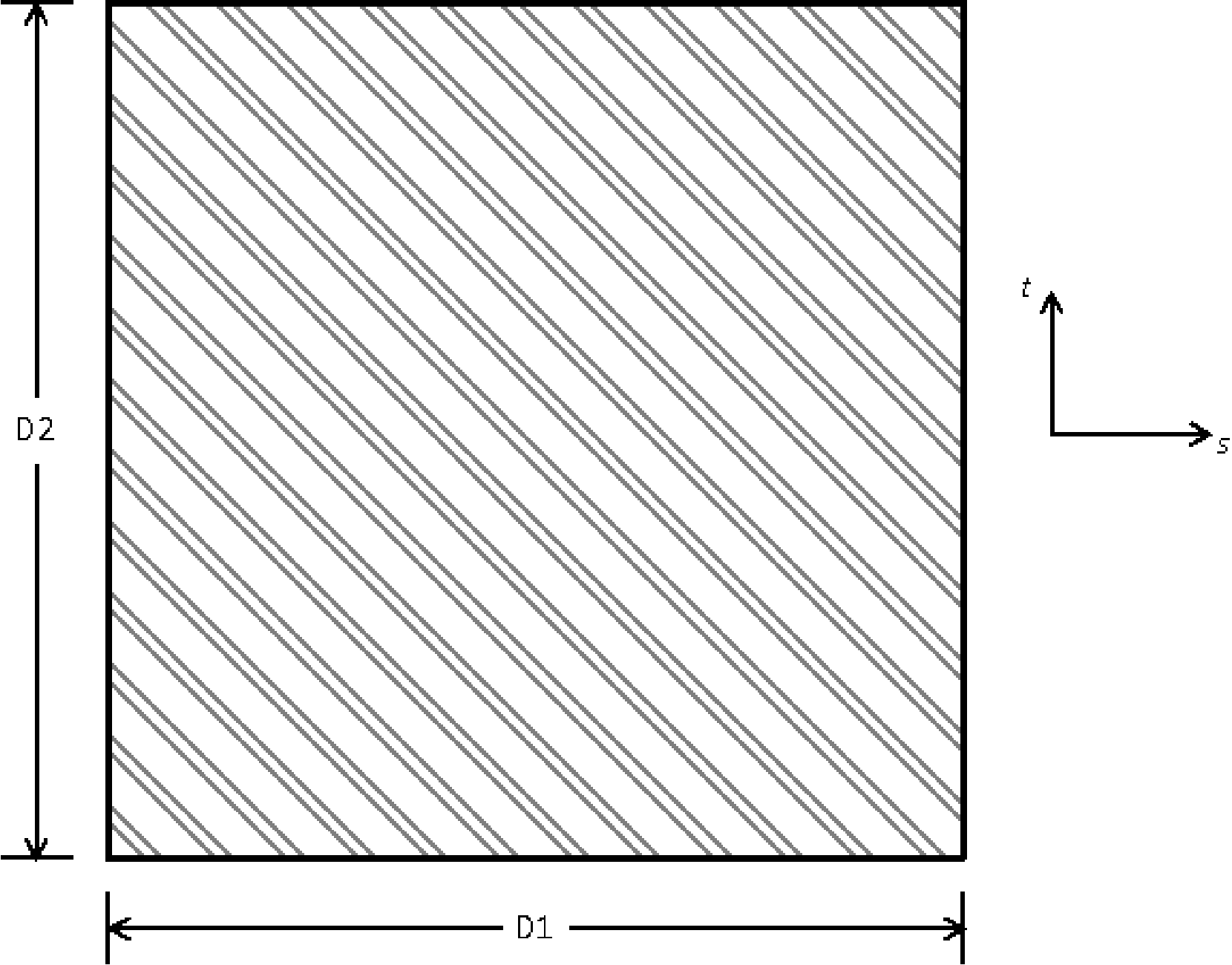

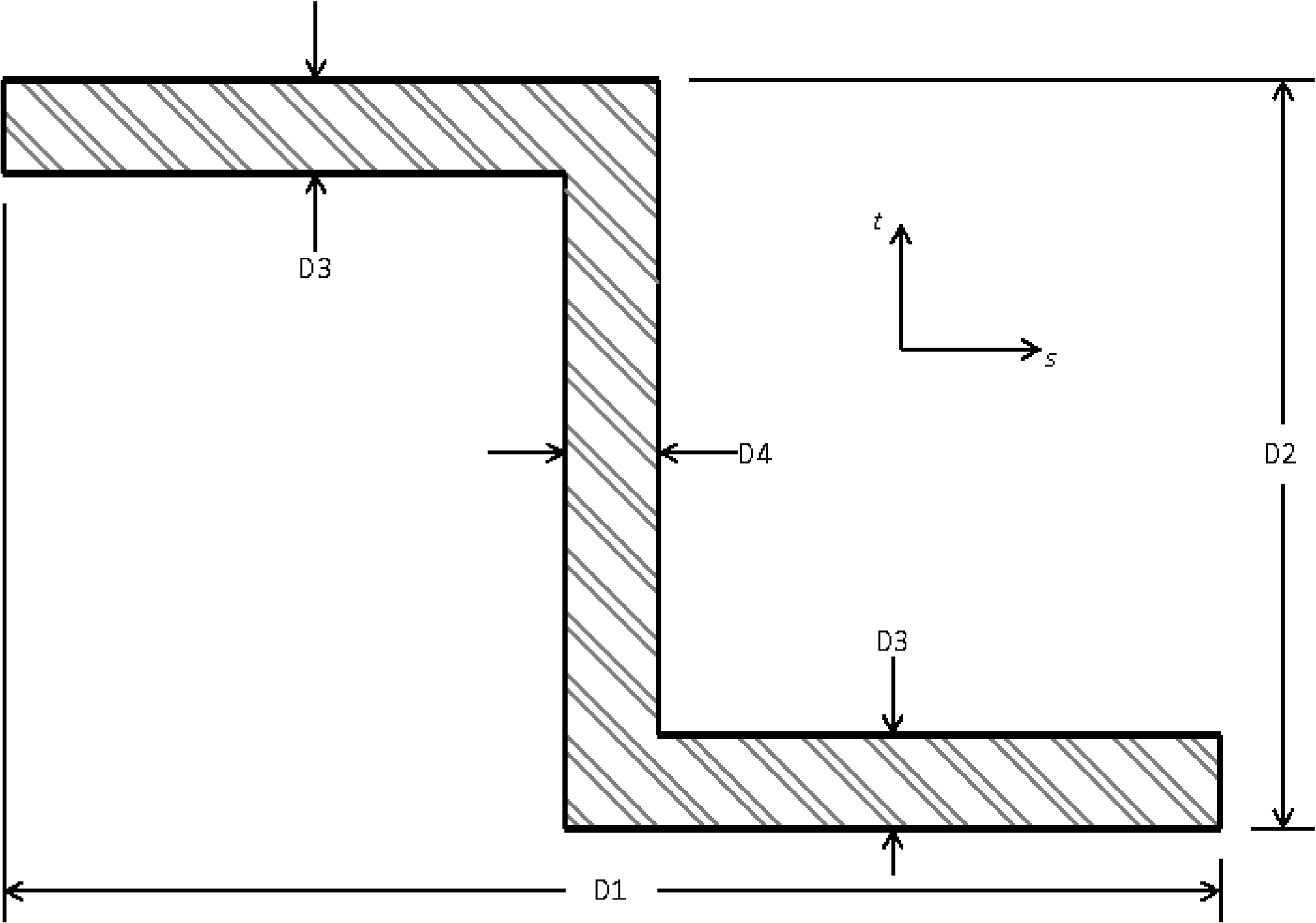

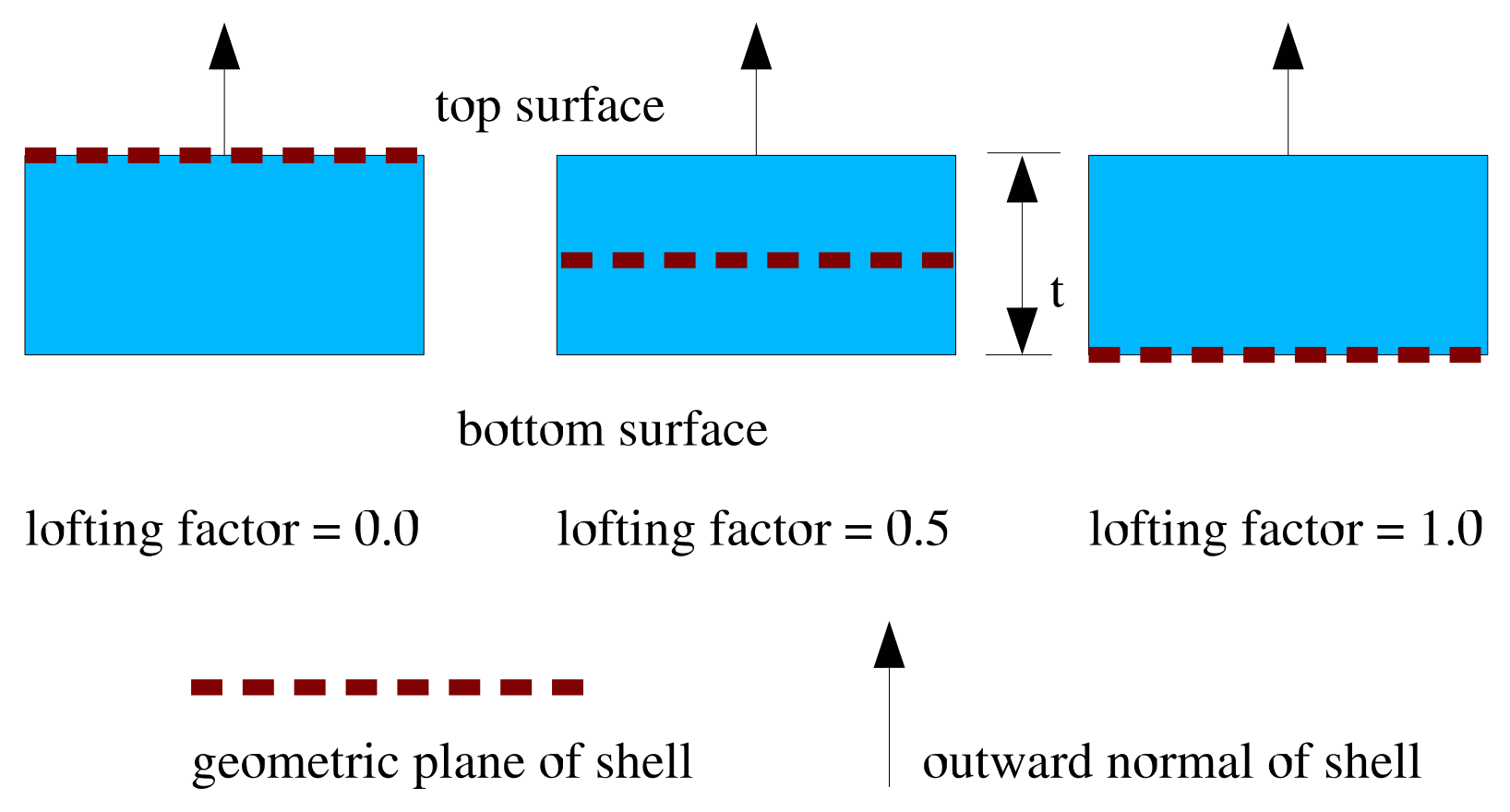

Fig. 6.4 shows an edge-on view of shell elements with a thickness of \(t\) and the location of the geometric plane in relation to the shell surfaces for three different values of the lofting factor – 0.0, 0.5, and 1.0. For a lofting factor of 0.0, the geometric surface defined by the shell corresponds to the top surface of the shell element. A lofting factor of 1.0 puts the geometric surface at the bottom surface of the shell element. The geometric surface is midway between the top and bottom surfaces for a lofting factor of 0.5, which is the default. Lofting factors greater than 1.0 or less than 0.0 are typically reserved for layering of shells – otherwise, this is not recommended.

Fig. 6.4 Location of geometric plane of shell for various lofting factors.

Consider the example of a lofting factor set to 1.0 for a shell with thickness of 0.2 inch. In this case, the top surface of the shell will be located at a distance of 0.2 inch from the geometric surface (measuring in the direction of the positive shell normal), and the bottom surface will be located at the geometric surface.

Both the shell mechanics and contact use shell lofting. See Section 8.4 for a discussion of lofting surfaces for shells and contact. It is recommended that shell lofting values other than 0.5 not be used if the shell is thick. If the shell is thicker than its in-plane width, the shell lofting algorithms may become unstable.

Sierra/SM can also initialize the lofting factor using an attribute defined on elements in the mesh file. The lofting factor can be set using any field present on the input mesh. To specify a field other than the single-element attribute, use the following form of the LOFTING FACTOR MESH VARIABLE command line:

LOFTING FACTOR MESH VARIABLE = <string>var_name

Here, the string var_name is the name of the initializing field.

A third, and slightly different way lofting can be implemented is through the command

OFFSET MESH VARIABLE = <string>var_name

which allows an offset value to be read from an attribute (or variable) on the mesh file. This attribute (or variable) must be named but may have any name, and this name is specified in place of var_name in the command. An offset is a dimensional (i.e., not scaled by the shell thickness) value that gives the shell mid-plane shift in the positive shell normal direction. Internal to Sierra/SM the offset value is converted to an equivalent lofting factor by dividing by the initial thickness and adding 0.5. Thus, an offset of zero gives a lofting factor of 0.5, an offset of one half of the thickness gives a lofting factor of one, and an offset of negative one half of the thickness gives a lofting factor of zero. There is no check that given offset values produce lofting values between zero and one, which allows any offset to be specified but requires that care be exercised to avoid unstable lofted shells.

Warning

An offset and a lofting factor may not both be specified in the same shell section. Both determine the shell lofting and may conflict.

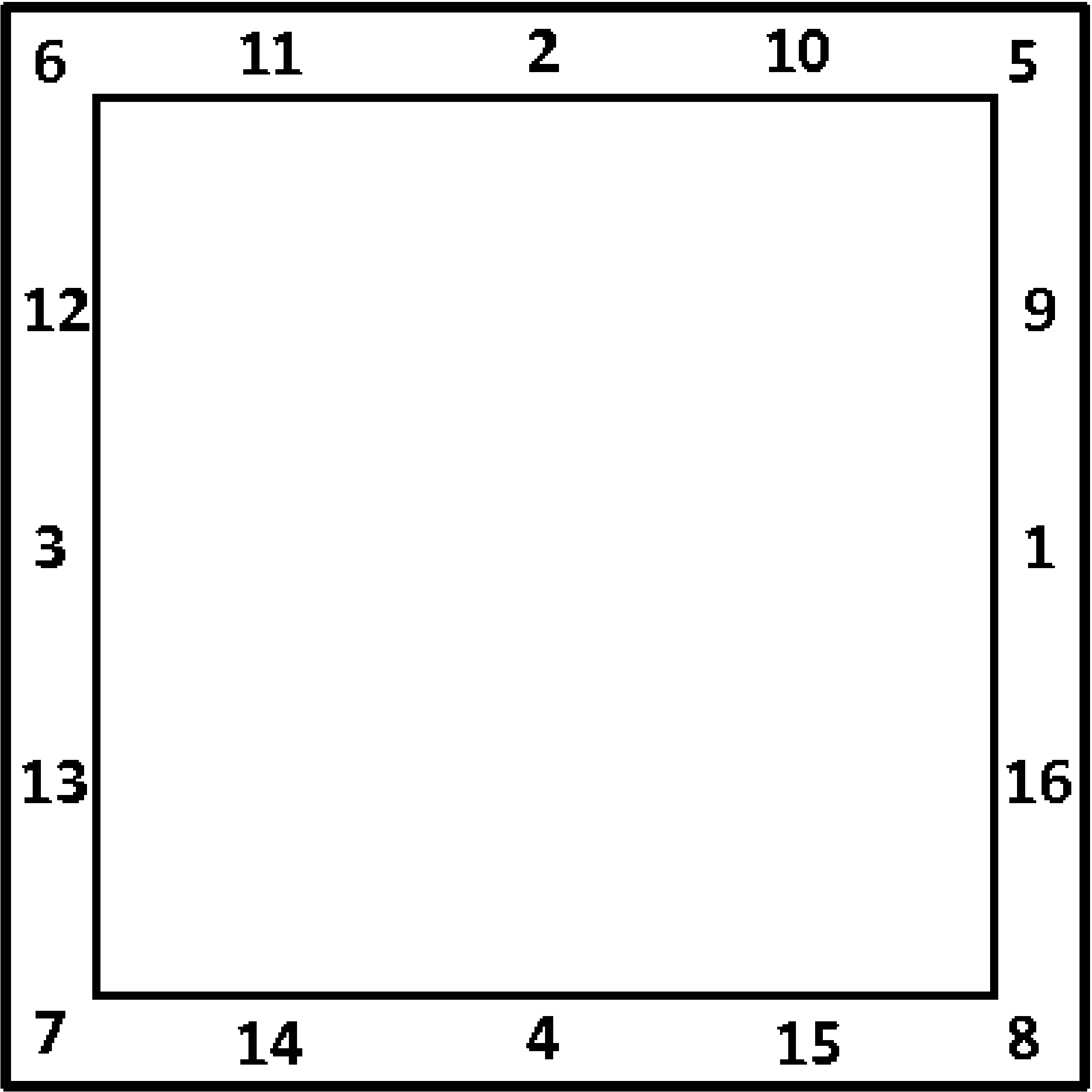

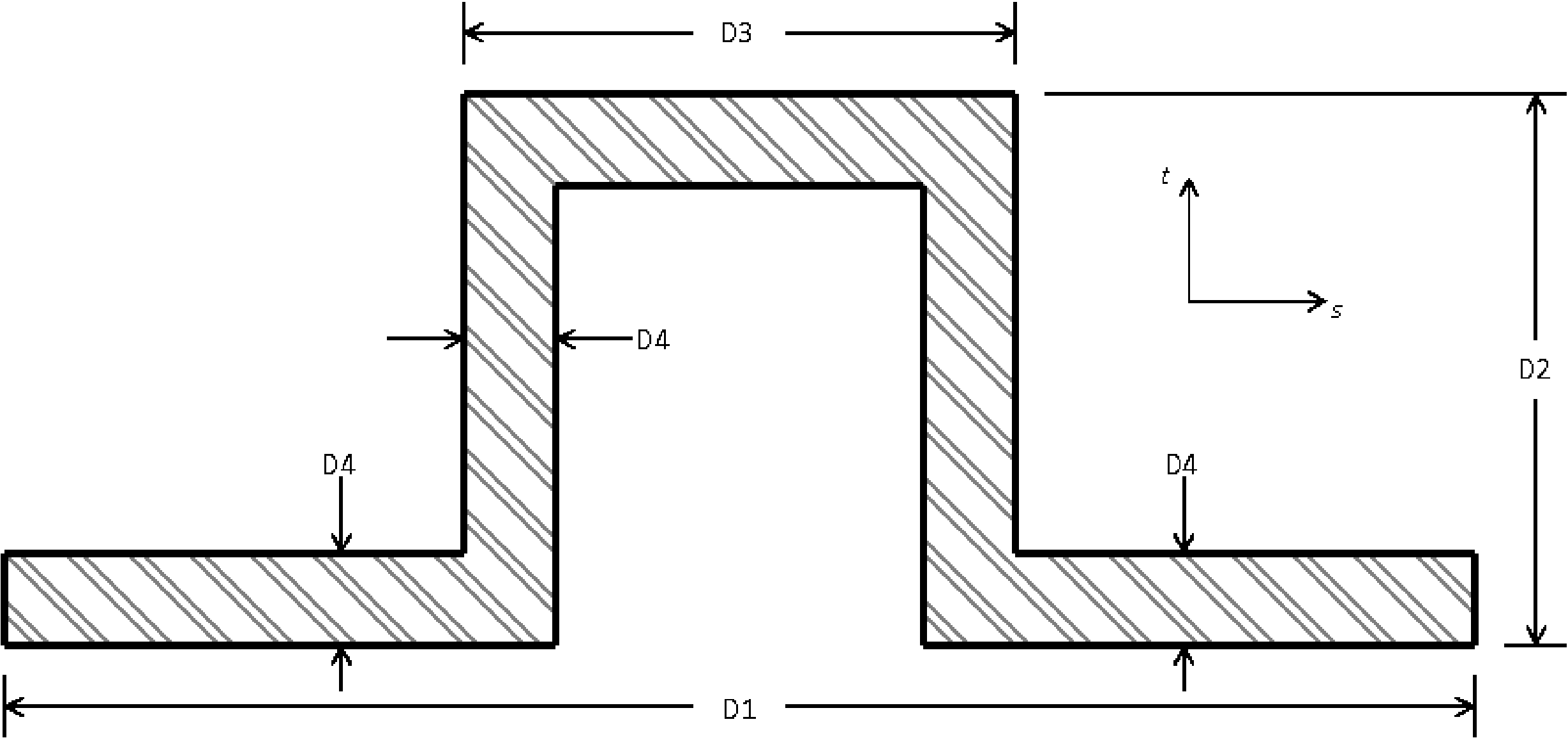

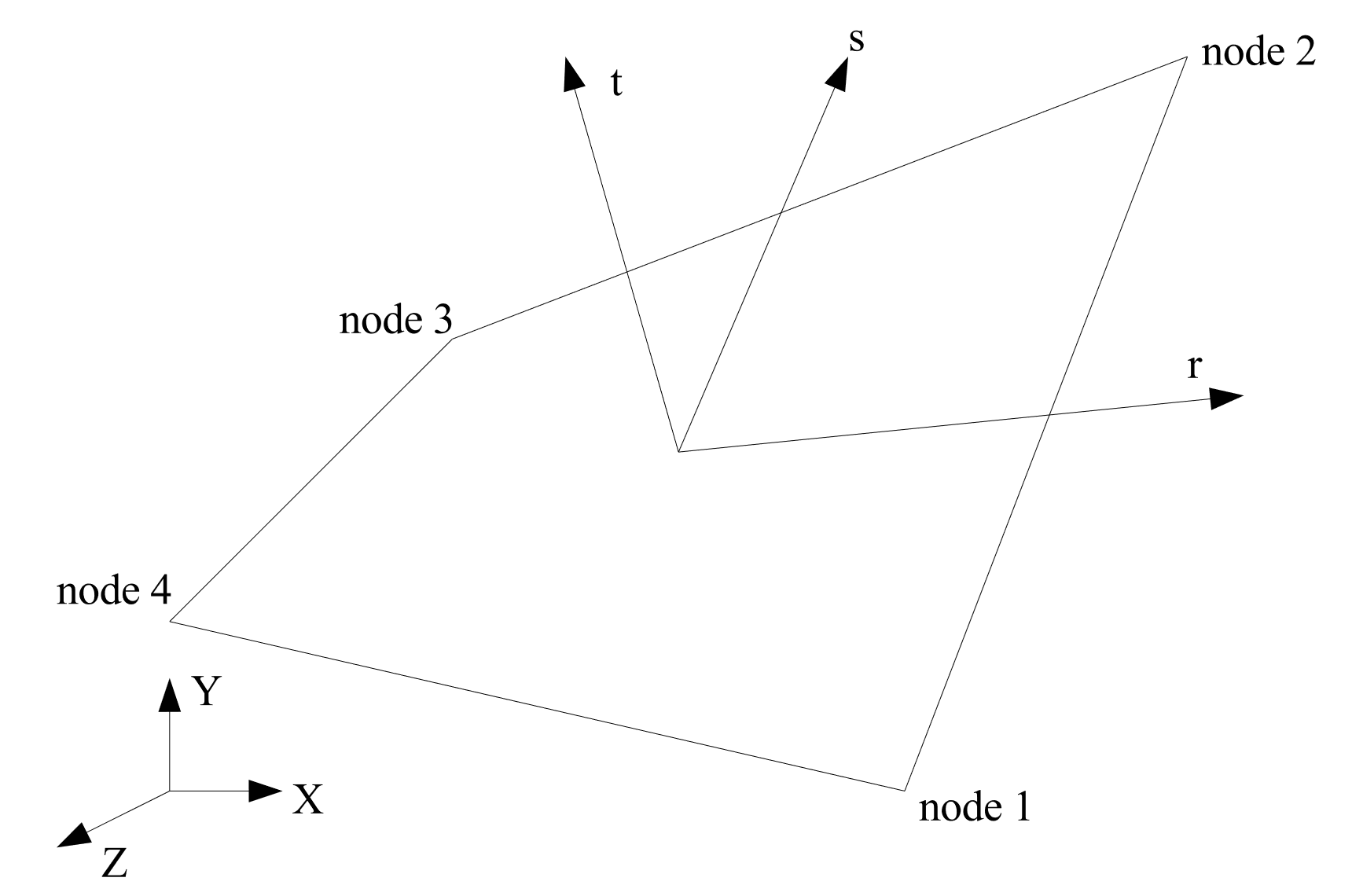

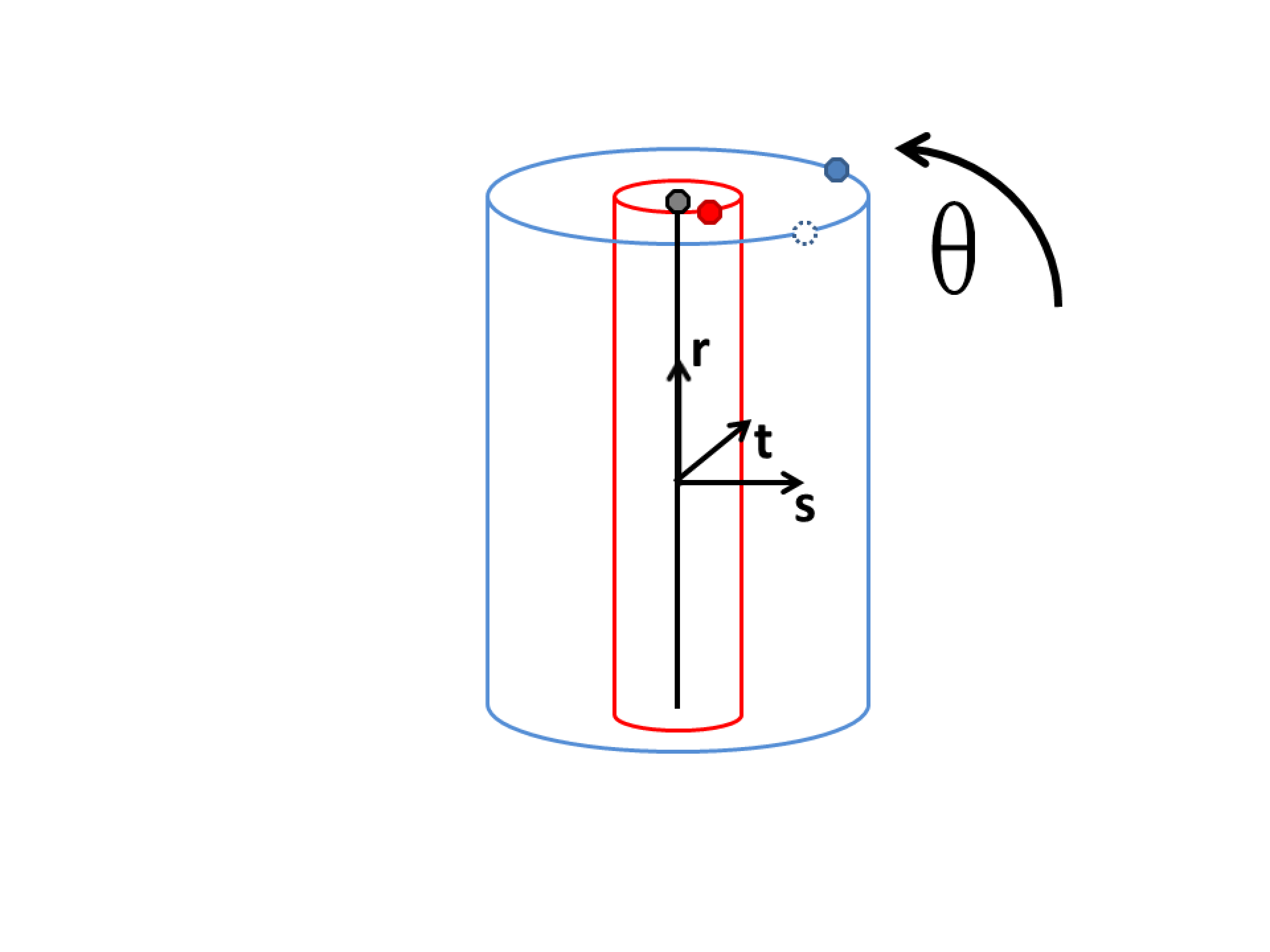

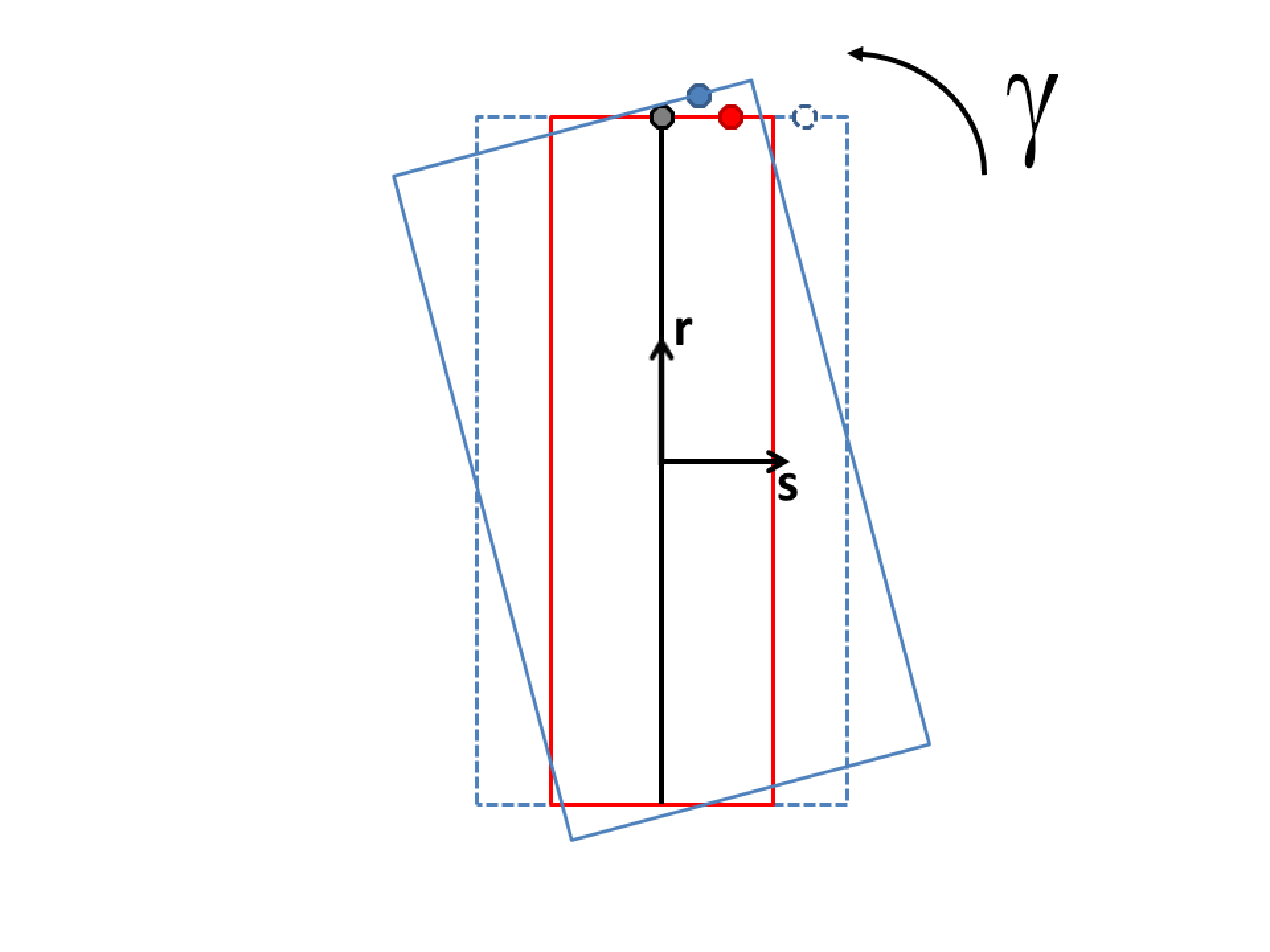

The ORIENTATION command line lets the user select a coordinate system for output of in-plane stresses and strains. The ORIENTATION option makes use of an embedded coordinate system \(r,s,t\) associated with each shell element. The \(r,s,t\) coordinate system for a shell element is shown in Fig. 6.5. The \(r\)-axis extends from the center of the shell to the midpoint of the side of the shell defined by nodes 1 and 2. The \(t\)-axis is located at the center of the shell and is normal to the surface of the shell at the center point. The \(s\)-axis is the cross-product of the \(t\)-axis and the \(r\)-axis. The \(r,s,t\)-axes form a local coordinate system at the center of the shell; this local coordinate system moves with the shell element as the element deforms.

Fig. 6.5 Local \(rst\) coordinate system for a shell element.

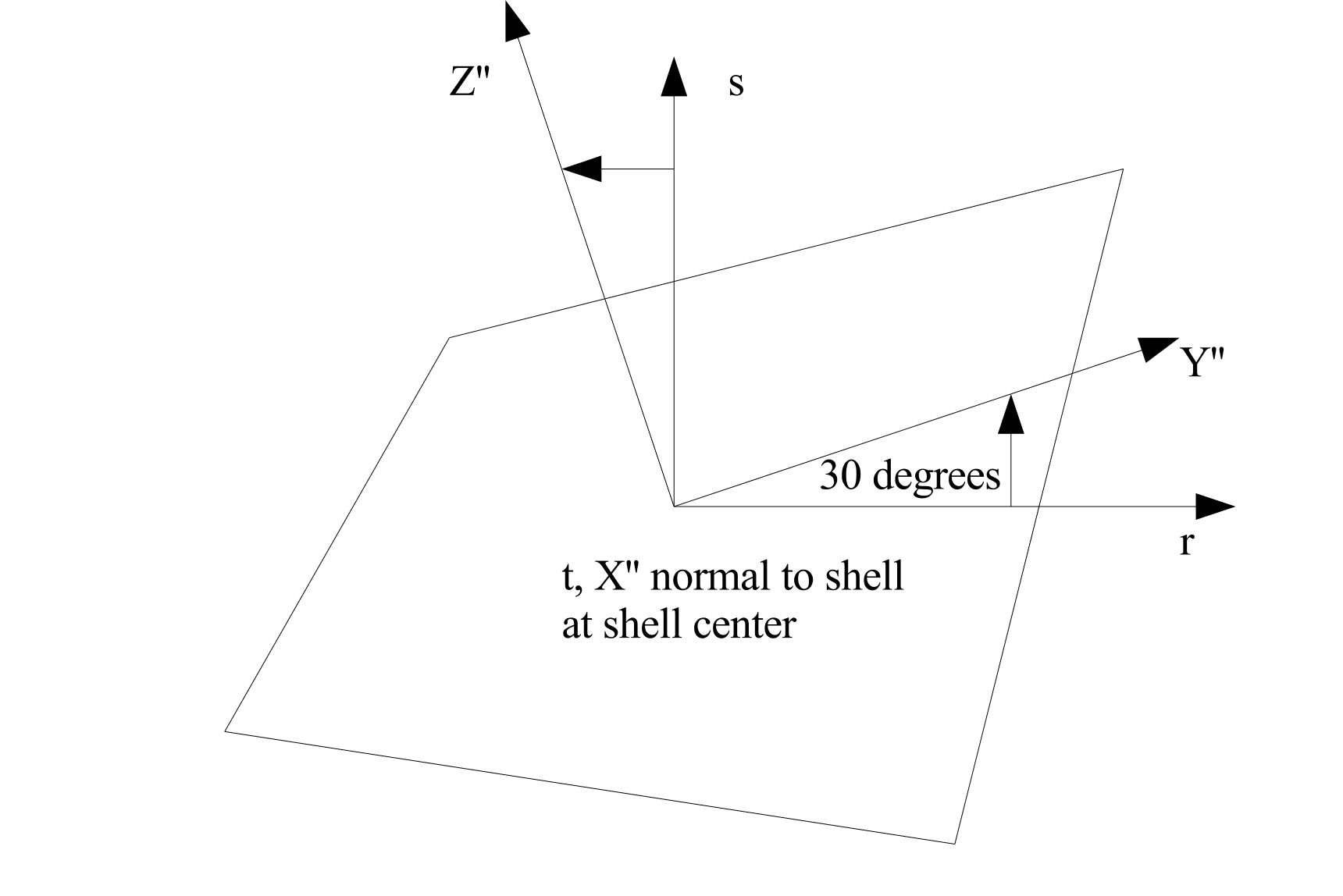

The ORIENTATION command line in the SHELL SECTION command block references an ORIENTATION command block that appears in the SIERRA scope. As described in Section 2 of this document, the ORIENTATION command block can be used to define a local co-rotational coordinate system \(X''Y''Z''\) at the center of a shell element. In the original shell configuration (time 0), one of the axes—\(X''\), \(Y''\), or \(Z''\)—is projected onto the plane of the shell element. The angle between this projected axis of the \(X''Y''Z''\) coordinate system and the \(r\)-axis is used to establish the transformation for in-plane stresses and strains. We will illustrate this with an example.

Suppose that in an ORIENTATION command block a rotation of 30 degrees about the 1-axis (\(X'\)-axis) has been specified. The command line for this rotation in the ORIENTATION command block would be

ROTATION ABOUT 1 = 30

For this case, the \(Y''\)-axis is projected onto the plane of the shell (Fig. 6.6). The angle between this projection and the \(r\)-axis establishes a transformation for the in-plane stresses of the shell (the stresses in the center of the shell lying in the plane of the shell). What will be output as the in-plane stress \(\sigma_{xx}^{ip}\) will be in the \(Y''\)-direction; what will be output as the in-plane stress \(\sigma_{yy}^{ip}\) will be in the \(Z''\)-direction. The in-plane stress \(\sigma_{xy}^{ip}\) is a shear stress in the \(Y''Z''\)-plane. The \(X''Y''Z''\) coordinate system maintains the same relative position in regard to the \(rst\) coordinate system. This means that the \(X''Y''Z''\) coordinate system is a local coordinate system that moves with the shell element as the element deforms.

Fig. 6.6 Rotation of 30 degrees about the 1-axis (\(X'\)-axis).

The following permutations for output of the in-plane stresses occur depending on the axis (1, 2, or 3) specified in the ROTATION ABOUT command line:

Rotation about the 1-axis (\(X'\)-axis): The in-plane stress \(\sigma_{xx}^{ip}\) will be in the \(Y''\)-direction; the in-plane stress \(\sigma_{yy}^{ip}\) will be in the \(Z''\)-direction. The in-plane stress \(\sigma_{xy}^{ip}\) is a shear stress in the \(Y''Z''\)-plane.

Rotation about the 2-axis (\(Y'\)-axis): The in-plane stress \(\sigma_{xx}^{ip}\) will be in the \(Z''\)-direction; the in-plane stress \(\sigma_{yy}^{ip}\) will be in the \(X''\)-direction. The in-plane stress \(\sigma_{xy}^{ip}\) is a shear stress in the \(Z''X''\)-plane.

Rotation about the 3-axis (\(Z'\)-axis): The in-plane stress \(\sigma_{xx}^{ip}\) will be in the \(X''\)-direction; the in-plane stress \(\sigma_{yy}^{ip}\) will be in the \(Y''\)-direction. The in-plane stress \(\sigma_{xy}^{ip}\) is a shear stress in the \(X''Y''\)-plane.

If no orientation is specified, the in-plane stresses and strains are output in the consistent axes from a default orientation, which is a rectangular system with the \(X'\) and \(Y'\) axes taken as the global \(X\) and \(Y\) axes, respectively, and ROTATION ABOUT 1 = 0.0.

The command line

DRILLING STIFFNESS FACTOR = <real>stiffness_factor

adds stiffness in the drilling degrees of freedom to quadrilateral shells. Drilling degrees of freedom are rotational degrees of freedom in the direction orthogonal to the plane of the shell at each node. The formulation used for the quadrilateral shells has no rotational stiffness in this direction. This can lead to spurious zero-energy modes of deformation similar in nature to hourglass deformation. This makes obtaining a solution difficult in quasistatic problems and can result in singularities when using the full tangent preconditioner.

The stiffness_factor should be chosen as a quantity small enough to add enough stiffness to allow the solve to be successful without unduly affecting the solution. The default value for stiffness_factor is 1.0e-5, which places drilling stiffness about 10000X lower than the bending stiffness. If singularities are encountered in the solution or hourglass-like deformation is observed in the drilling degrees of freedom, setting a larger value may be appropriate.

Elements in a section can be made rigid by including the RIGID BODY command line. The RIGID BODY command line specifies an indenter that maps to a rigid body command block. See Section 6.3.1 for a full discussion of how to create rigid bodies and Section 6.3.1.1 for information on the use of the RIGID BODIES FROM ATTRIBUTES command.

The command line

STABLE TIME STEP ESTIMATE specifies the method used to calculate the size of the critical time step. The default method is GERSCHGORIN circle theorem, which is used to find a bound to the maximum membrane, shear and bending frequencies of the problem. The COURANT method uses the characteristic length of the element and the membrane wave speed to approximate the stable time step. This estimate tends to be less conservative than GERSCHGORIN, but might not be appropriate for problems with dominant shear or bending responses. This command line option is only available for quadrilateral shells. Triangular shells will only use the Courant estimate.

The command lines CONTACT SHELL THICKNESS and CONTACT SHELL LOFTING can be used to set the thickness and lofting factor for use in contact. This can be a different thickness or lofting factor than used for defining the element stiffness.

6.2.5.1. Orthotropic Properties

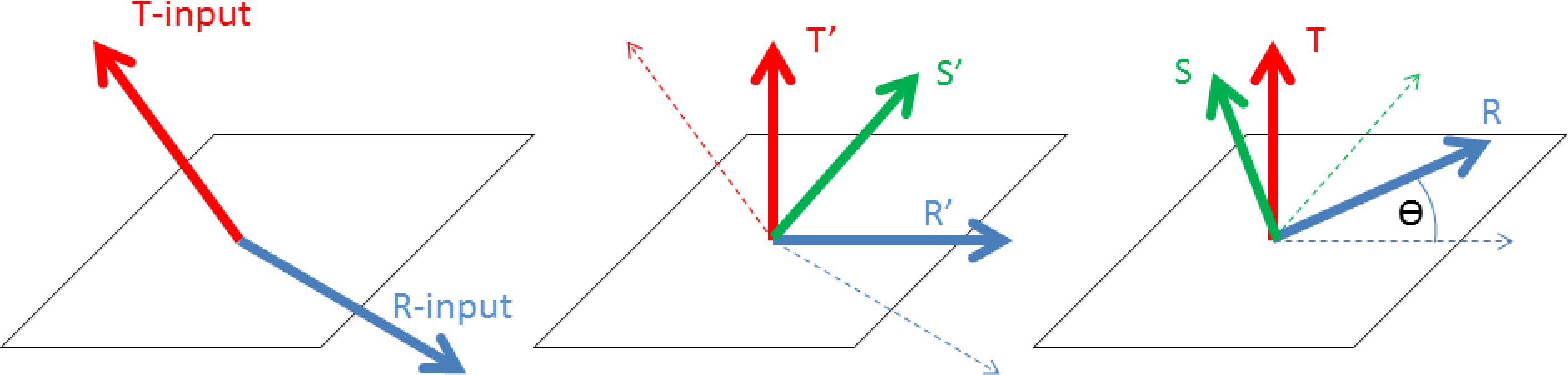

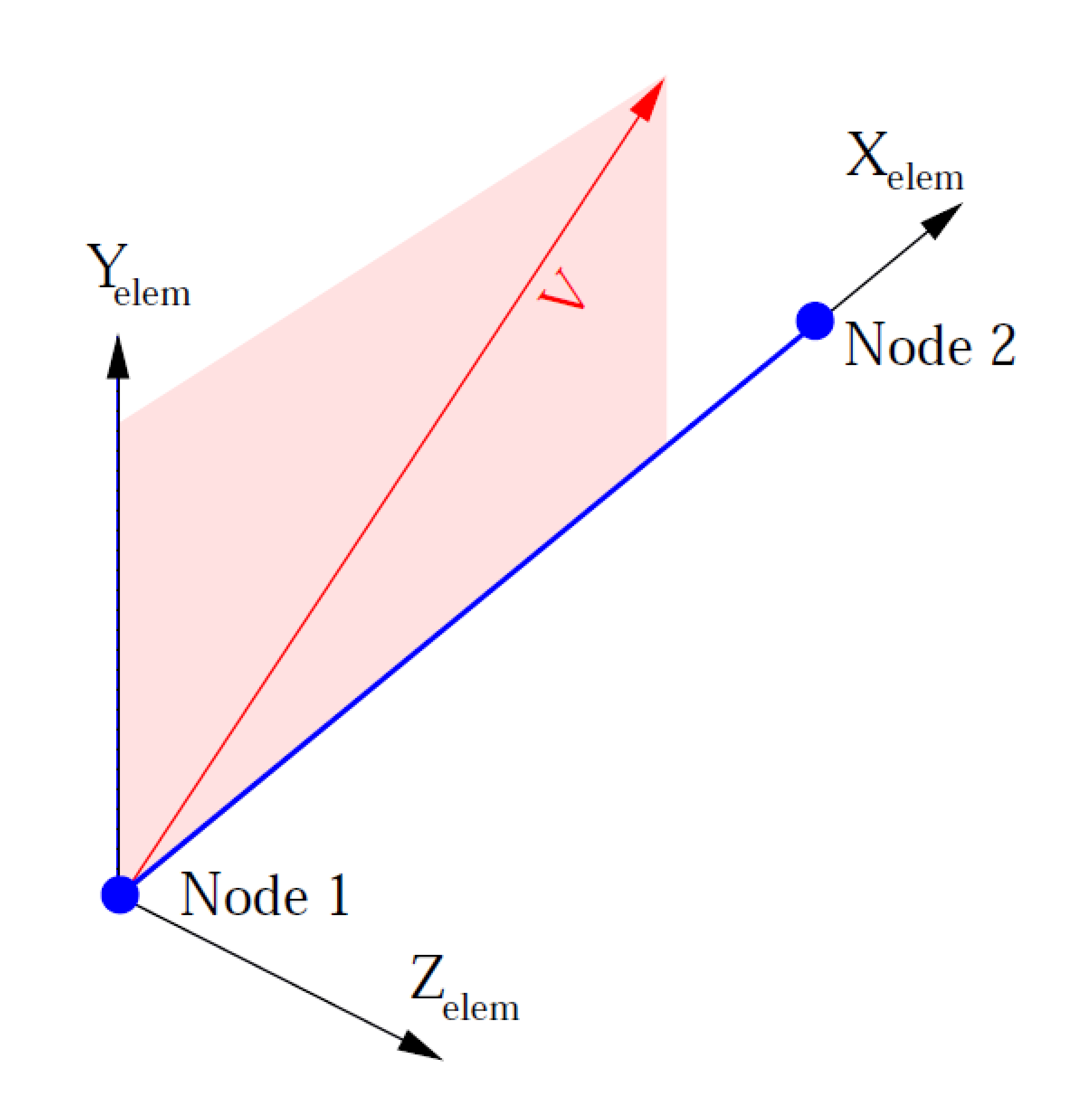

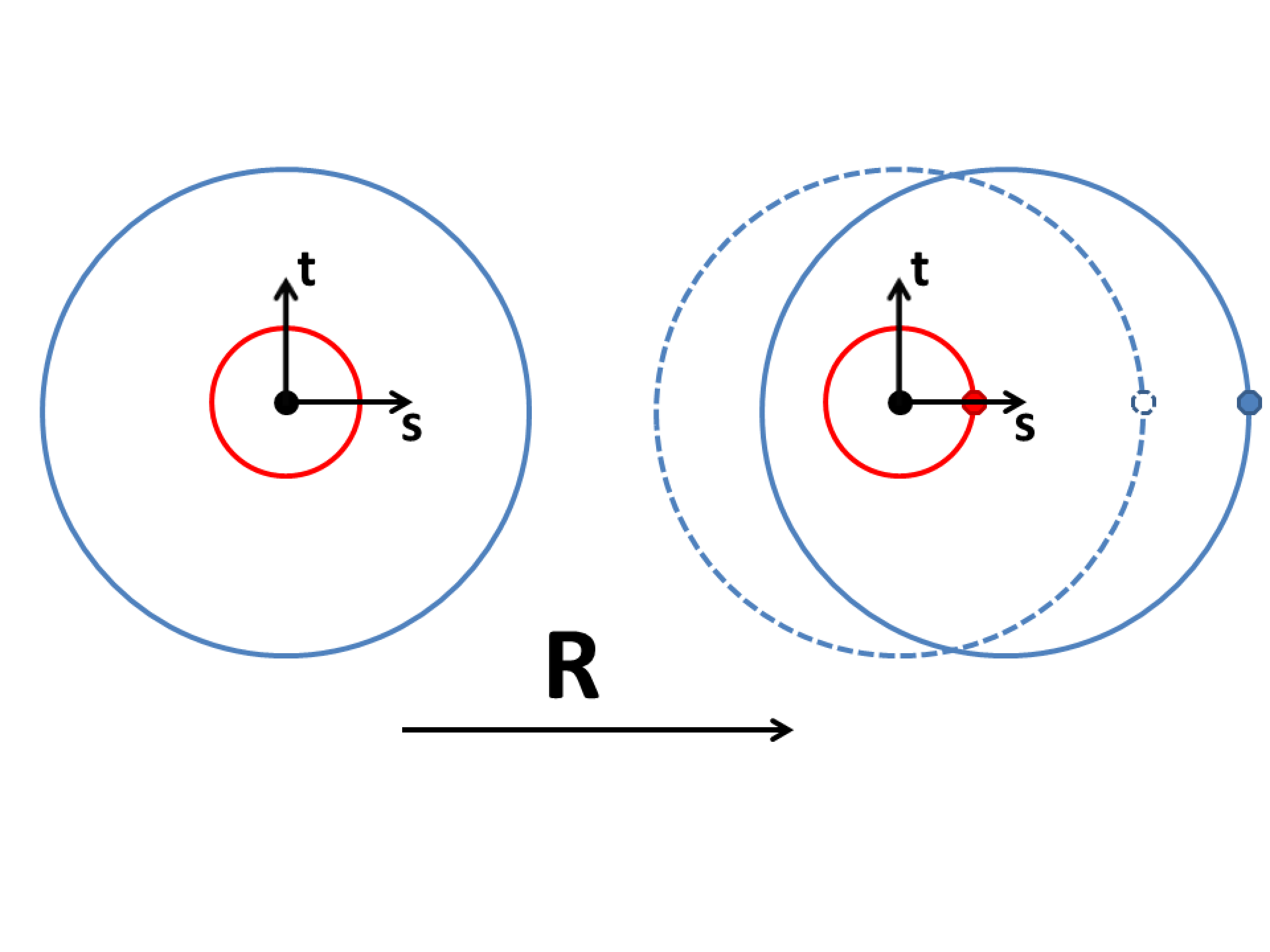

Orthotropic shell materials define their properties within a characteristic coordinate system. This element-local \(R,S,T\) coordinate system may be defined using the FIBER ORIENTATION, R VECTOR READ VARIABLE, and T VECTOR READ VARIABLE commands. Command lines R VECTOR READ VARIABLE and T VECTOR READ VARIABLE specify the element fields which contain vectors \(R_{\textrm{input}}\) and \(T_{\textrm{input}}\), respectively, used to define this coordinate system, while FIBER ORIENTATION specifies an in-plane rotation of this element-wise coordinate system.

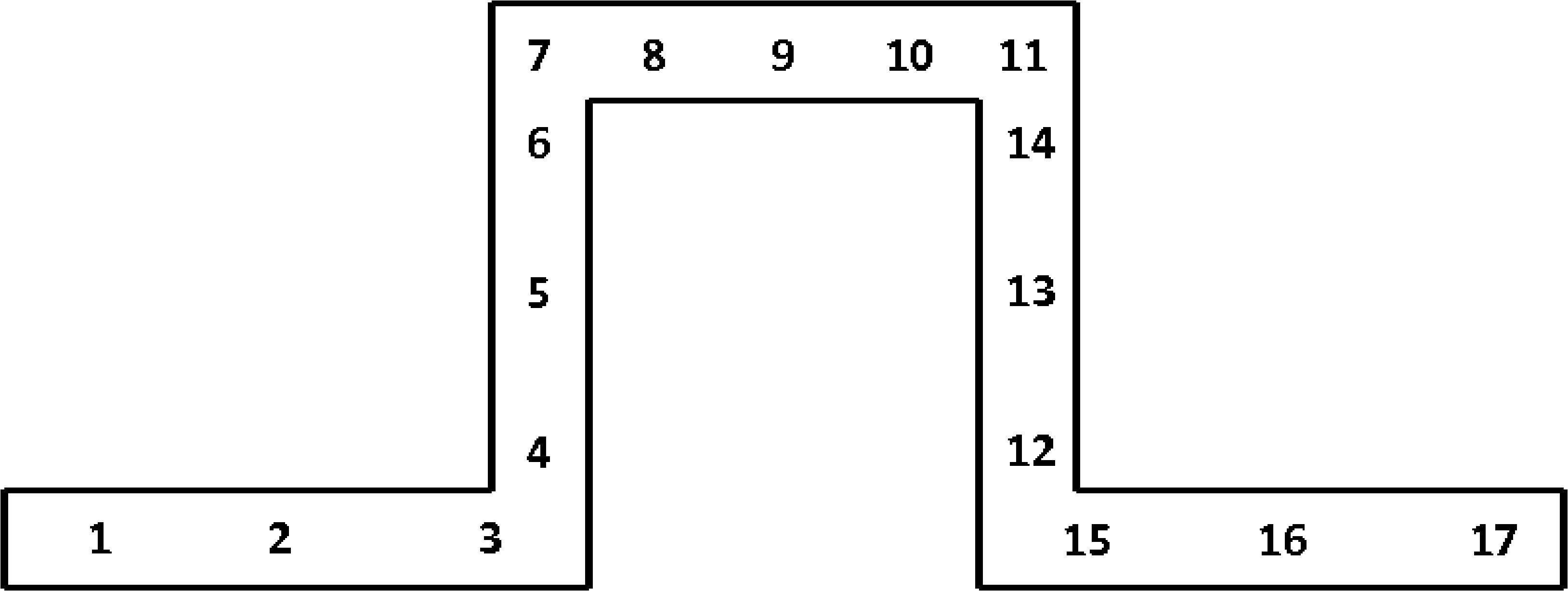

Construction of the local coordinate system, demonstrated graphically in Fig. 6.7, is performed in the undeformed configuration; the coordinate system moves with its associated shell element throughout the analysis. The orientation of \(T_{\textrm{input}}\) determines whether the positive or negative shell normal is selected as the out-of-plane \(T\)-direction. Intermediate direction \(R'\) is computed by projecting \(R_{\textrm{input}}\) into the plane of the shell, such that it is orthogonal to \(T\). The third orthogonal direction is computed as \(S'= T \times R'\). Rotating intermediate directions \(R'\) and \(S'\) about the \(T\)-axis by the specified FIBER ORIENTATION angle \(\Theta\) yields the final local \(R,S,T\) coordinate system. The \(R\), \(S\), and \(T\) directions can be visualized by requesting element fields “r_vector,” “s_vector,” and “t_vector,” respectively, in results output. Additional guidance on the output and visualization of element quantities is available in Section 9.3.

Fig. 6.7 Definition of shell \(R,S,T\) coordinate system.

6.2.6. Layered Shell Section

BEGIN LAYERED SHELL SECTION <string>sect

LAYER <int>layerId = <string>subSectName

<string>material <string>model

LOFTING FACTOR = <real>loft(0.5)

CONTACT THICKNESS = <real>contactThickness

CONTACT LOFTING FACTOR = <real>contactLofting

END

The LAYERED SHELL SECTION command block is used to define a single shell element that is a composite of layers with different properties. The layers of the shell can have different materials and different shell formulations.

Internally to the code a layered shell is represented by several individual elements that share the same nodes and same topology. Layered shells will create new element blocks and new elements in the output file to represent each distinct shell layer. Boundary conditions such as contact or element death can be performed on either the original shell element or on the individual layers specifying the appropriate block name.

The LAYER defines a layer for the current shell. The layers of the shell will be stacked from the bottom to the top based on the order of the LAYER commands on the input deck. A shell may have up to 99 different layers defined. The layerId input is a positive integer provided by the user. This number will be used to label the shell layers to aid in visualization. The new element block sub-layers will be named based on the provided layerId using the convention

<block_name>_SIERRA_CREATED_LAYER<layerID>

The subSectName is the name of the shell section associated with the layer. The shell section will be used to define the thickness of the layer and any shell formulation options to use in the layer. The material and model names define the material and material model that the layer is composed of. Any material that is valid for shell elements can be used as a shell layer material. A default material and model may be provided in the parameters for block command block. Any layer in the section that does not define a material and model will use this default material and model.

Note that the first order approximations used in the shell element formulation does not accurately compute transverse shear strains for layered shells. This is handled and corrected internally by applying a shear correction factor [[10]].

The lofting factor for the entire shell stack can be specified with the LOFTING FACTOR option. Similar to standard shells this lofting factor can vary from 0.0 to 1.0 and has a default value of 0.5 (shell element passes through mid-plane of the layered shell stack.) The lofting of the individual layers will be computed automatically based on the layer thicknesses and layered shell lofting factor.

The command lines CONTACT SHELL THICKNESS and CONTACT SHELL LOFTING can be used to set the thickness and lofting factor for use in contact. These commands define the contact behavior of the layered shell stack as a whole.

Example of layered shell syntax:

begin shell section SHELL_1

thickness = 0.1

end shell section SHELL_1

begin shell section SHELL_2

thickness = 0.2

end shell section SHELL_2

begin shell section SHELL_3

thickness = 0.1

end shell section SHELL_3

begin layered shell section LAYERED_SHELL

layer 1 = SHELL_1 steel elastic

layer 2 = SHELL_2 copper elastic_plastic

lofting factor = 1.0

end

begin parameters for block block_1

section = LAYERED_SHELL

end

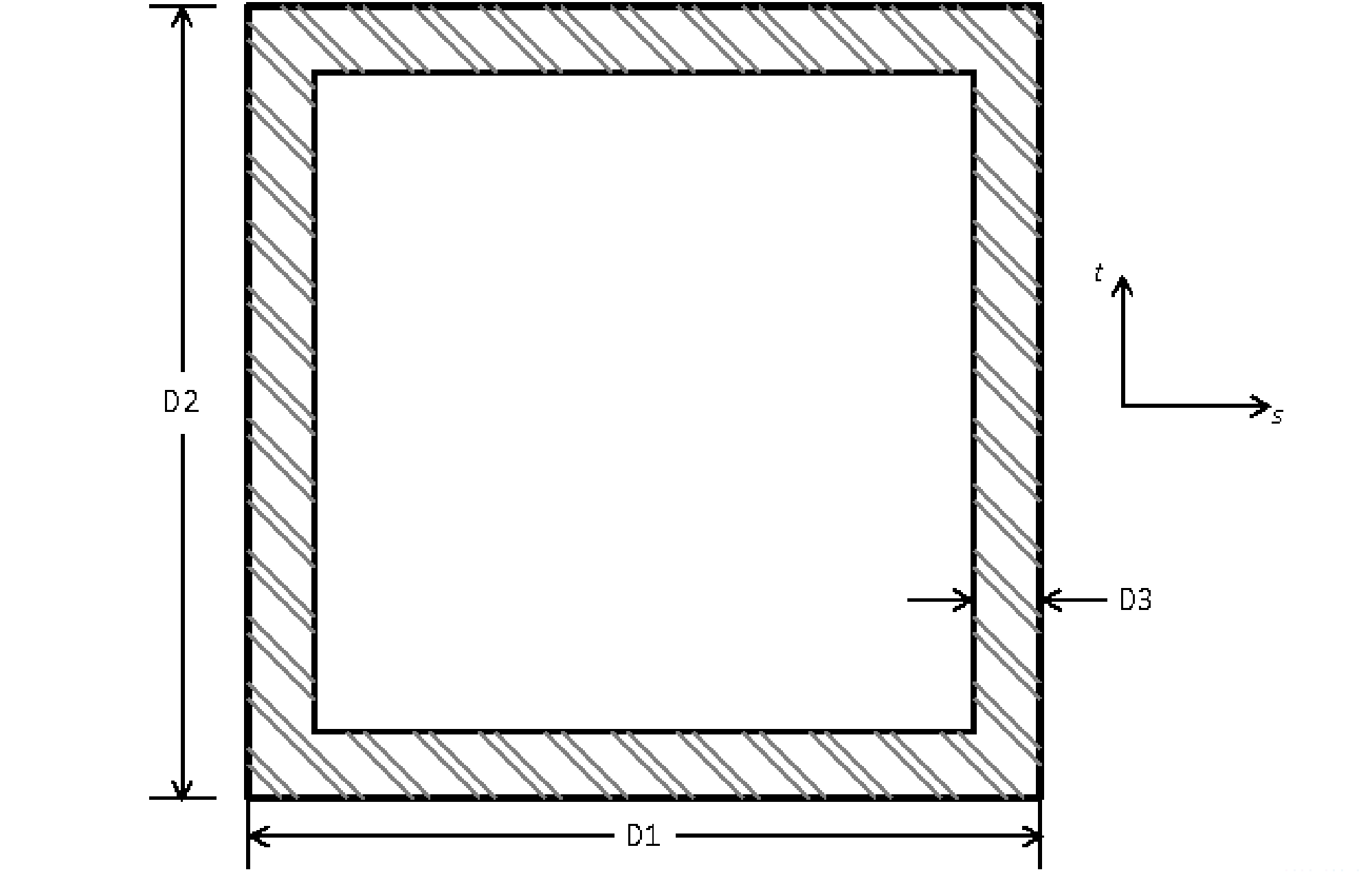

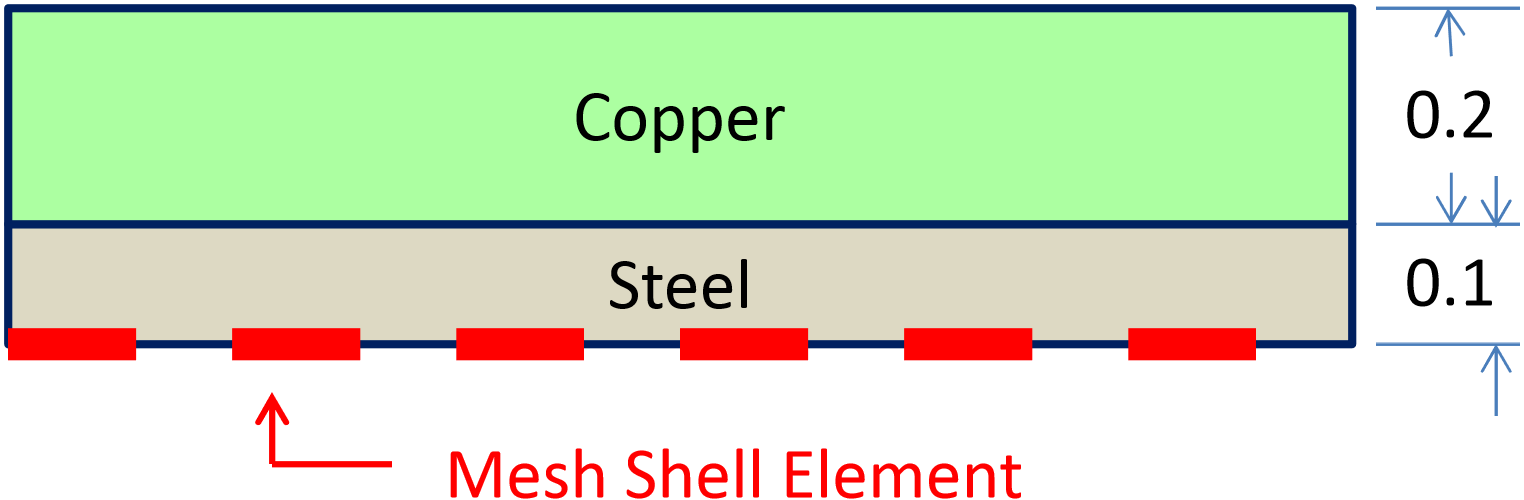

In the above example a two layer shell is defined. The composite shell has thickness of 0.3. The bottom layer of the shell is made of elastic steel with a thickness of 0.1. On top of the steel is a 0.2 thick layer of elastic plastic copper. The entire layer stack-up has a lofting factor of 1.0 with respect to the shell element. The configuration is shown in Fig. 6.8. The layer specific resultants on the different shell layers can be seen by looking in the results output file element blocks named block_1_SIERRA_CREATED_LAYER_1 and block_1_SIERRA_CREATED_LAYER_2.

Fig. 6.8 Layered shell example.

6.2.7. Membrane Section

BEGIN MEMBRANE SECTION <string>membrane_section_name

THICKNESS = <real>mem_thickness

THICKNESS MESH VARIABLE =

<string>THICKNESS|<string>var_name

THICKNESS TIME STEP = <real>time_value

THICKNESS SCALE FACTOR = <real>thick_scale_factor(1.0)

CONTACT THICKNESS SCALE FACTOR = <real>thick_scale_factor(thick_scale_factor)

FORMULATION = <string>MEAN_QUADRATURE|

SELECTIVE_DEVIATORIC(MEAN_QUADRATURE)

DEVIATORIC PARAMETER = <real>deviatoric_param

LOFTING FACTOR = <real>lofting_factor(0.5)

LOFTING FACTOR MESH VARIABLE = <string>var_name

RIGID BODY = <string>rigid_body_name

RIGID BODIES FROM ATTRIBUTES = <integer>first_id

TO <integer>last_id

CONTACT THICKNESS = <real>contactThickness

CONTACT LOFTING FACTOR = <real>contactLofting

END [MEMBRANE SECTION <string>membrane_section_name]

The MEMBRANE SECTION command block specifies the properties for a membrane element. If a section defined by this command block is referenced in the parameters for a block of four-noded elements, the elements in that block will be treated as membranes. The parameter membrane_section_name is user-defined and is referenced by a SECTION command line in a PARAMETERS FOR BLOCK command block.

Either a THICKNESS command line or a THICKNESS MESH VARIABLE command line must appear in the MEMBRANE SECTION command block.

If a membrane element block references a MEMBRANE SECTION command block with the command line

THICKNESS = <real>mem_thickness

then all the membrane elements in the block will have their thickness initialized to the value mem_thickness.

Sierra/SM can also initialize the thickness using an attribute defined on elements in the mesh file. Meshing programs such as PATRAN and CUBIT typically set the element thickness as an attribute on the elements. If the elements have one and only one attribute defined on the mesh, the THICKNESS MESH VARIABLE command line should be specified as

THICKNESS MESH VARIABLE = THICKNESS

which causes the thickness of the element to be initialized to the value of the attribute for that element. If there are zero attributes or more than one attribute, the thickness variable will not be automatically defined, and the command will fail.

The thickness may also be initialized by any other field present on the input mesh. To specify a field other than the single-element attribute, use this form of the THICKNESS MESH VARIABLE command line:

THICKNESS MESH VARIABLE = <string>var_name

where the string var_name is the name of the initializing field.

The input mesh may have values defined at more than one point in time. To choose the point in time in the mesh file that the variable should be read, use the command line:

THICKNESS TIME STEP = <real>time_value

The default time point in the mesh file at which the variable is read is 0.0.

Once the thickness of a membrane element is initialized by using either the THICKNESS command line or the THICKNESS MESH VARIABLE command line, this initial thickness value can then be scaled by using the scale factor command line:

THICKNESS SCALE FACTOR = <real>thick_scale_factor

If the initial thickness of the membrane is 0.15 units, and the value for thick_scale_factor is 0.5, then the scaled thickness of the membrane will be 0.075 units.

CONTACT THICKNESS SCALE FACTOR = <real>contact_thick_scale_factor

The CONTACT THICKNESS SCALE FACTOR command is used for overwriting the value of THICKNESS SCALE FACTOR for contact purposes.

If the initial thickness of the membrane is 0.15 inch, the value of thick_scale_factor is 0.5, and the value of contact_thick_scale_factor is 1.0, then the membrane contact thickness will be equal to the original thickness (0.15) inches.

The FORMULATION command line specifies whether the element will use a single-point integration rule (mean quadrature) or a selective-deviatoric integration rule:

FORMULATION = <string>MEAN_QUADRATURE|SELECTIVE_DEVIATORIC

(MEAN_QUADRATURE)

If the user wishes to use the selective-deviatoric rule, the DEVIATORIC PARAMETER command line must also appear in the MEMBRANE SECTION command block:

DEVIATORIC PARAMETER = <real>deviatoric_param

The selective-deviatoric elements, when used with a parameter greater than 0.0, provide hourglass control without artificial hourglass parameters. The selective-deviatoric parameter, deviatoric_param, which is valid from 0.0 to 1.0, indicates how much of the deviatoric response should be taken from a uniform-gradient integration and how much should be taken from a full integration of the element. A value of 0.0 will give a pure uniform-gradient response with no hourglass control. Thus, this value is of little practical use. A value of 1.0 will give a fully integrated deviatoric response. Although any value between 0.0 and 1.0 is perfectly valid, lower values are generally preferred.

The command line

LOFTING FACTOR = <real>lofting_factor(0.5)

allows the user to shift the location of the mid-surface of a membrane element relative to the geometric location of the membrane element. By default, the geometric location of a membrane element in a mesh represents the mid-surface of the membrane. If a membrane has a thickness of 0.2 inch, the top surface of the membrane is 0.1 inch above the geometric surface defined by the membrane element, and the bottom surface of the membrane is 0.1 inch below the geometric surface defined by the membrane element. (The top surface of the membrane is the surface with a positive element normal; the bottom surface of the membrane is the surface with a negative element normal.)

Fig. 6.4 illustrates shell lofting, which is also applicable to membranes. For membranes, Fig. 6.4 represents an edge-on view of membrane elements with a thickness of \(t\) and the location of the geometric plane in relation to the membrane surfaces for three different values of the lofting factor—0.0, 0.5, and 1.0. For a lofting factor of 0.0, the geometric surface defined by the membrane corresponds to the top surface of the membrane element. A lofting factor of 1.0 puts the geometric surface at the bottom surface of the membrane element. The geometric surface is midway between the top and bottom surfaces for a lofting factor of 0.5, which is the default.

Consider the example of a lofting factor set to 1.0 for a membrane with thickness of 0.2 inch. In this case, the top surface of the membrane will be located at a distance of 0.2 inch from the geometric surface (measuring in the direction of the positive shell normal), and the bottom surface will be located at the geometric surface.

Both the membrane mechanics and contact use membrane lofting. See Section 8.4 for a discussion of lofting surfaces for membranes and contact.

Sierra/SM can also initialize the lofting factor using an attribute defined on elements in the mesh file. The lofting factor can be set using any field present on the input mesh. To specify a field other than the single-element attribute, use the following form of the LOFTING FACTOR MESH VARIABLE command line:

LOFTING FACTOR MESH VARIABLE = <string>var_name

Here, the string var_name is the name of the initializing field.

Elements in a section can be made rigid by including the RIGID BODY command line. The RIGID BODY command line specifies an indenter that maps to a rigid body command block. Consult Section 6.3.1 for a full description of how to create rigid bodies and Section 6.3.1.1 for information on the use of the RIGID BODIES FROM ATTRIBUTES command.

The command lines CONTACT SHELL THICKNESS and CONTACT SHELL LOFTING can be used to set the thickness and lofting factor for use in contact. The thickness used for contact can be different that the thickness used for the element stiffness calculations.

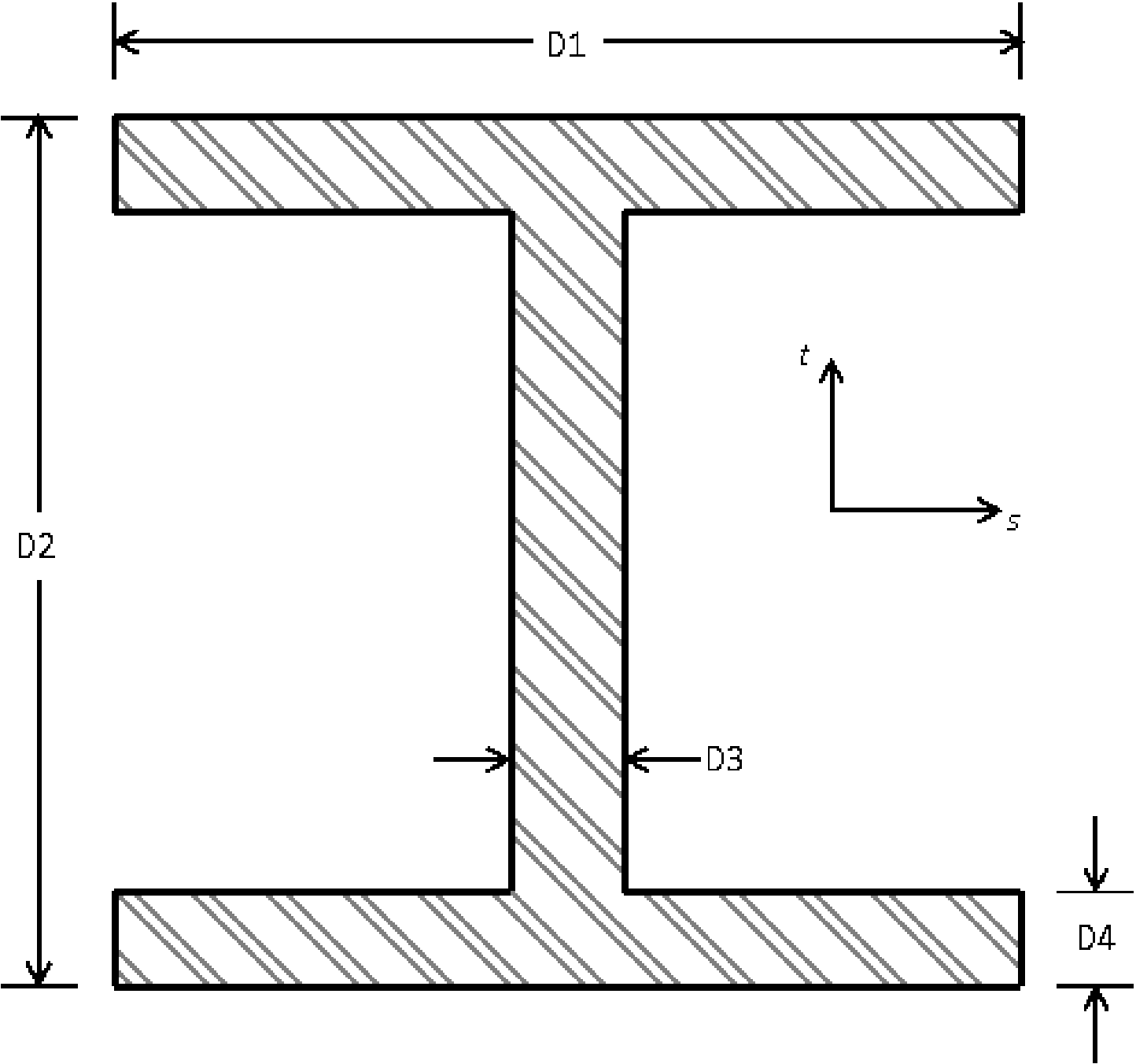

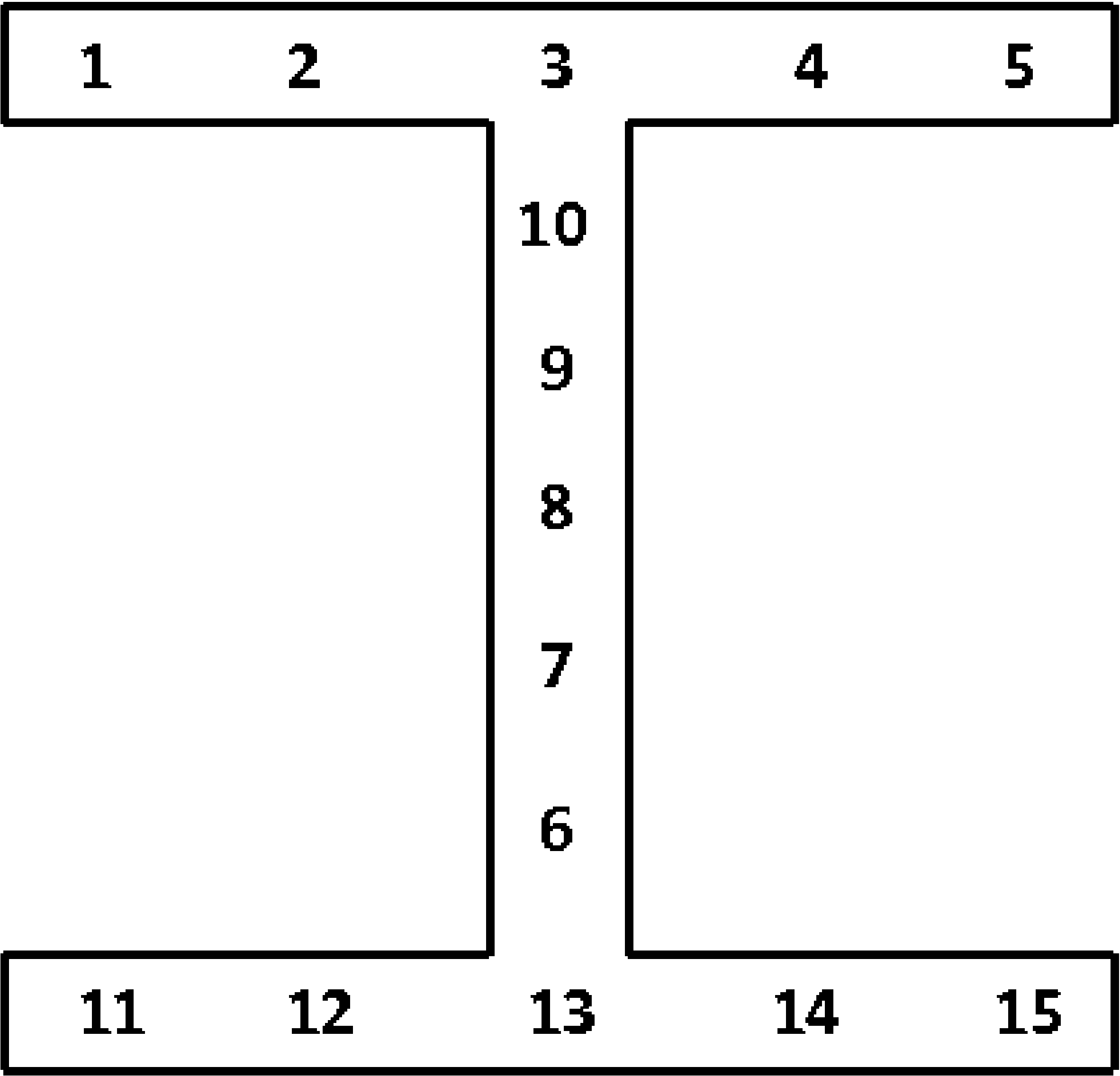

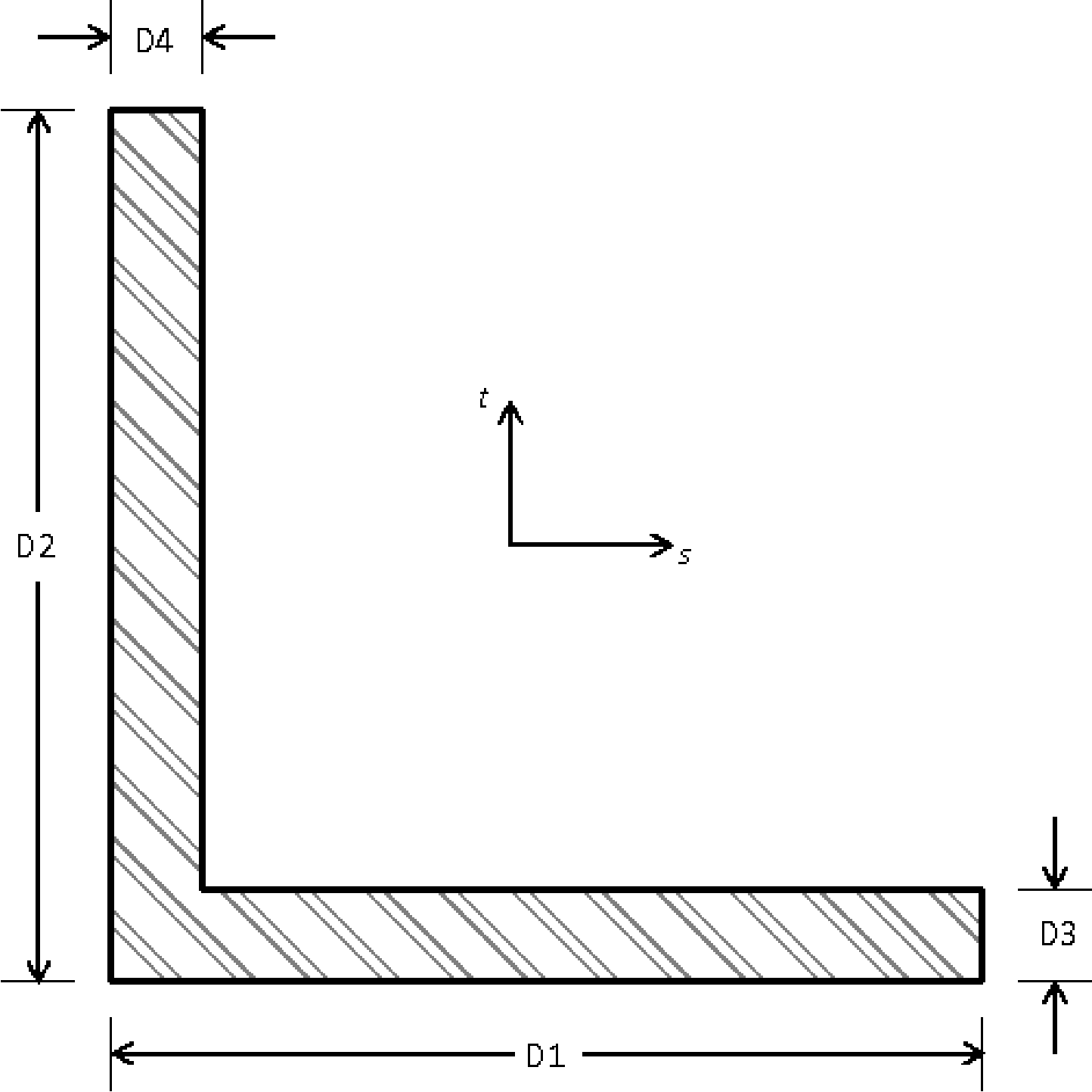

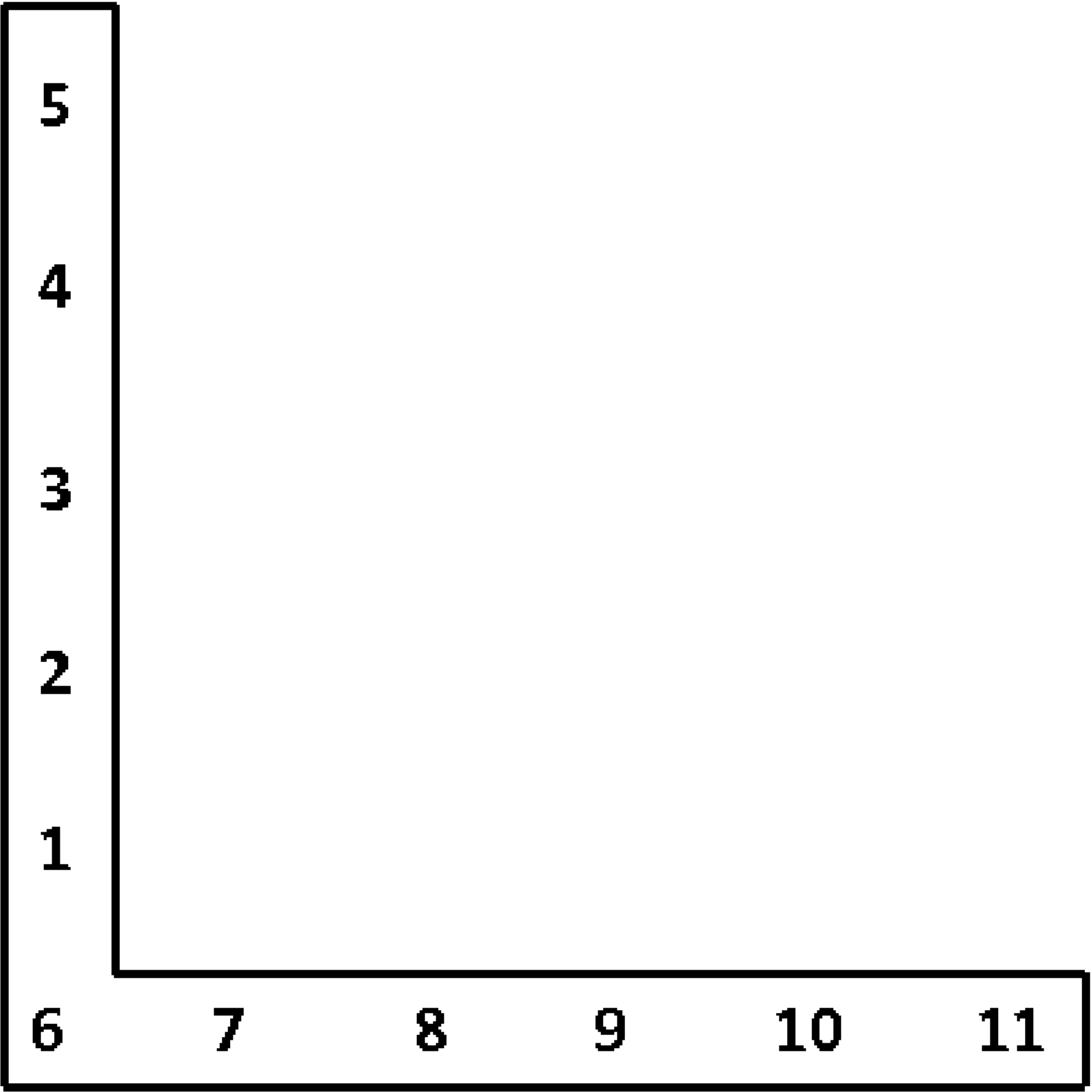

6.2.8. Beam Section

BEGIN BEAM SECTION <string>beam_section_name

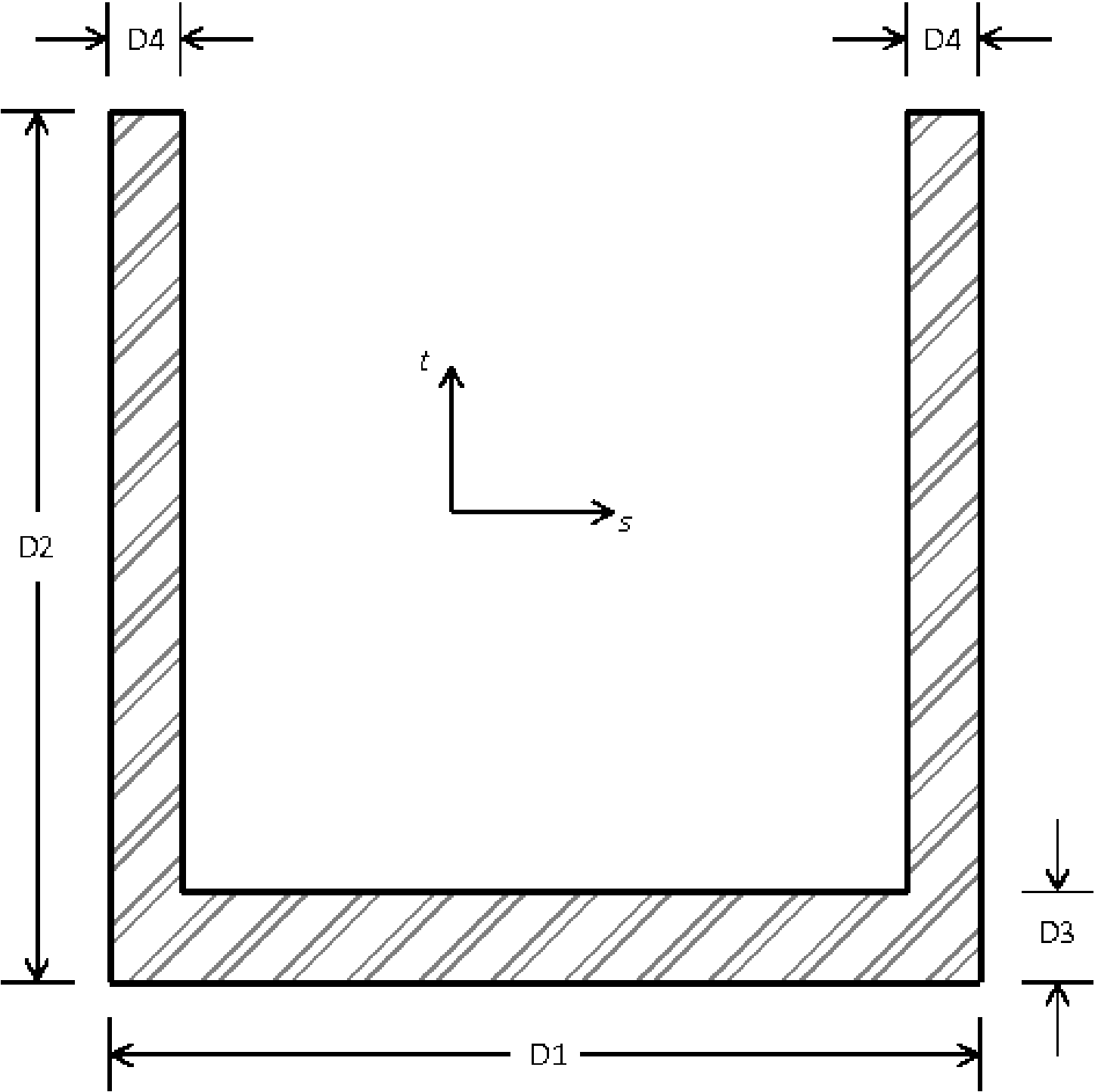

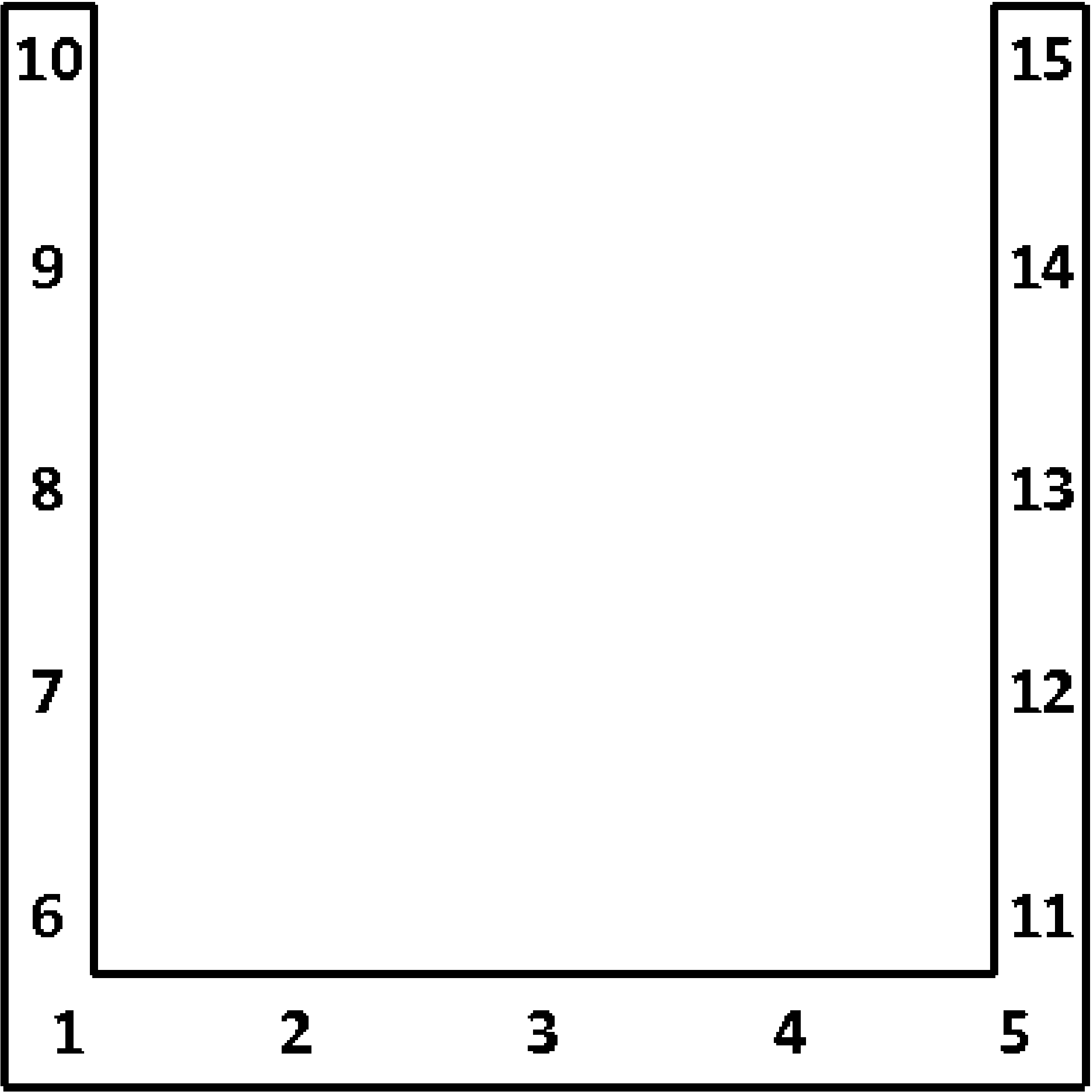

SECTION = ROD|TUBE|BAR|BOX|I|L|T|T1|C1|C2|Z|HAT|I2

#

# Section dimensions, definition depends on particular section type.

#

D1 = <real>d1

D1 VARIABLE = <STRING>d1_var

D2 = <real>d2

D2 VARIABLE = <STRING>d2_var

D3 = <real>d3

D3 VARIABLE = <STRING>d3_var

D4 = <real>d4

D4 VARIABLE = <STRING>d4_var

D5 = <real>d5

D5 VARIABLE = <STRING>d5_var

D6 = <real>d6

D6 VARIABLE = <STRING>d6_var

T AXIS = <real>tx <real>ty <real>tz

T AXIS VARIABLE = <string>t_axis_var

REFERENCE AXIS = <string>CENTER|RIGHT|

TOP|LEFT|BOTTOM(CENTER)

AXIS OFFSET = <real>s_offset <real>t_offset

AXIS OFFSET GLOBAL = <real>x_offset <real>y_offset <real>z_offset

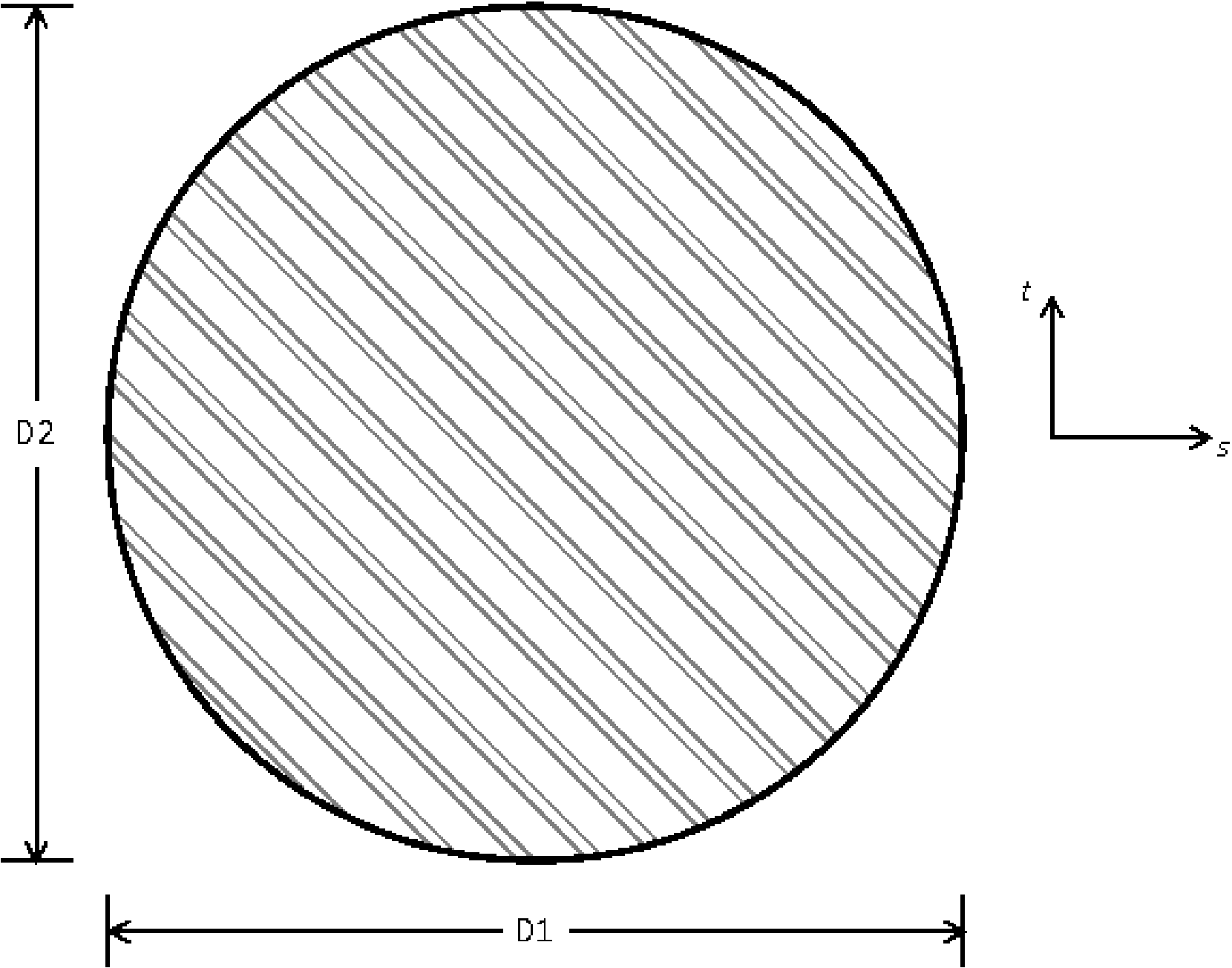

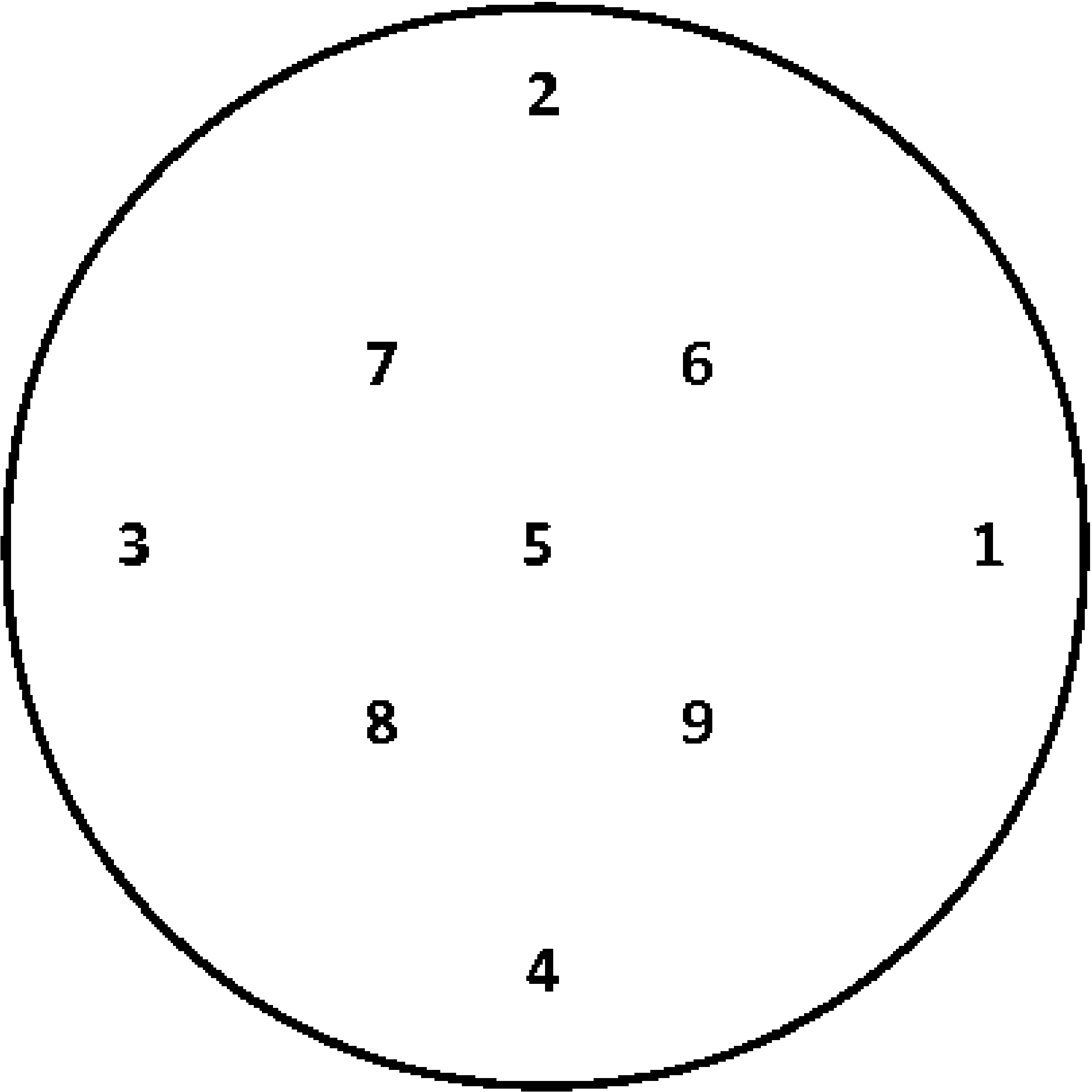

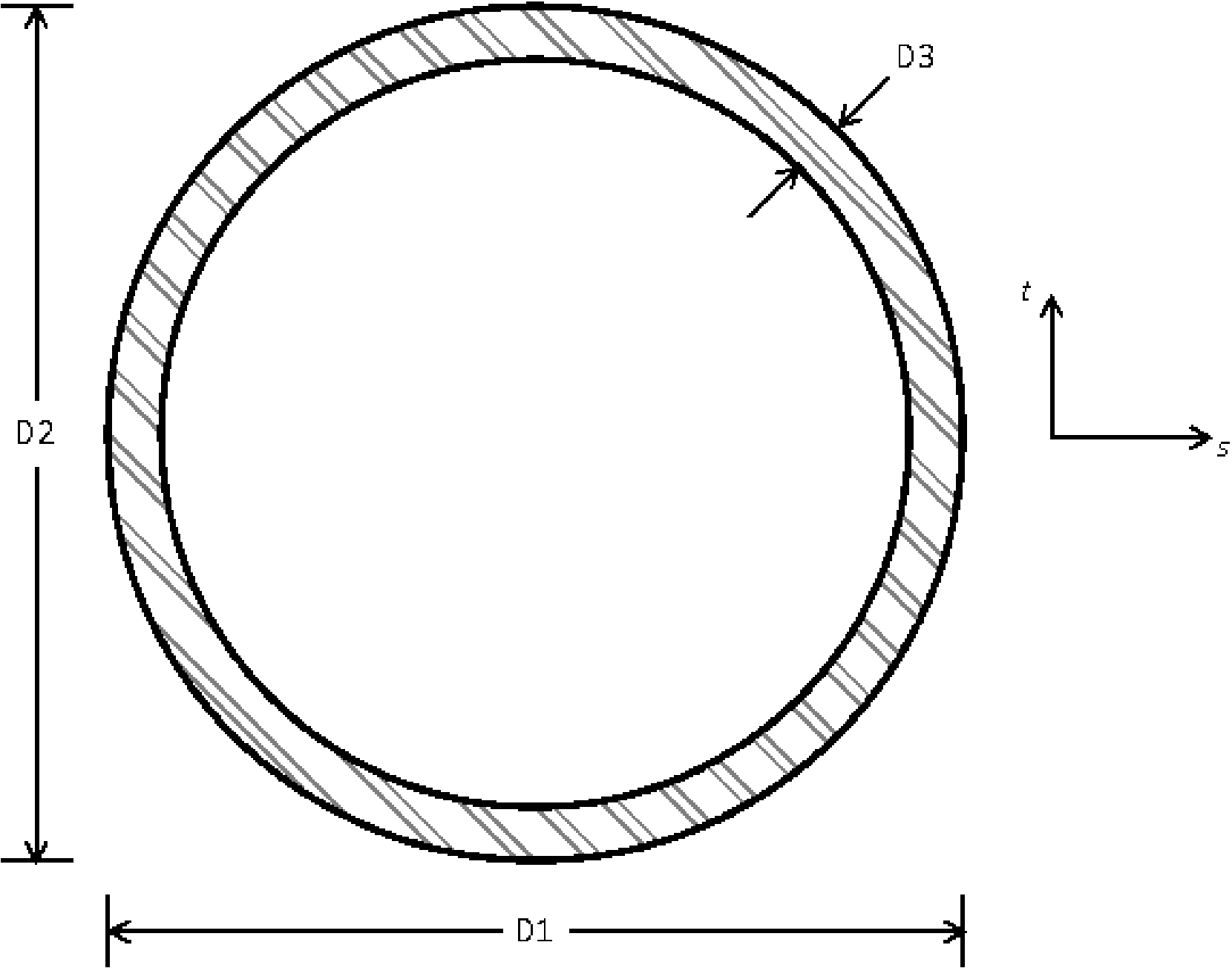

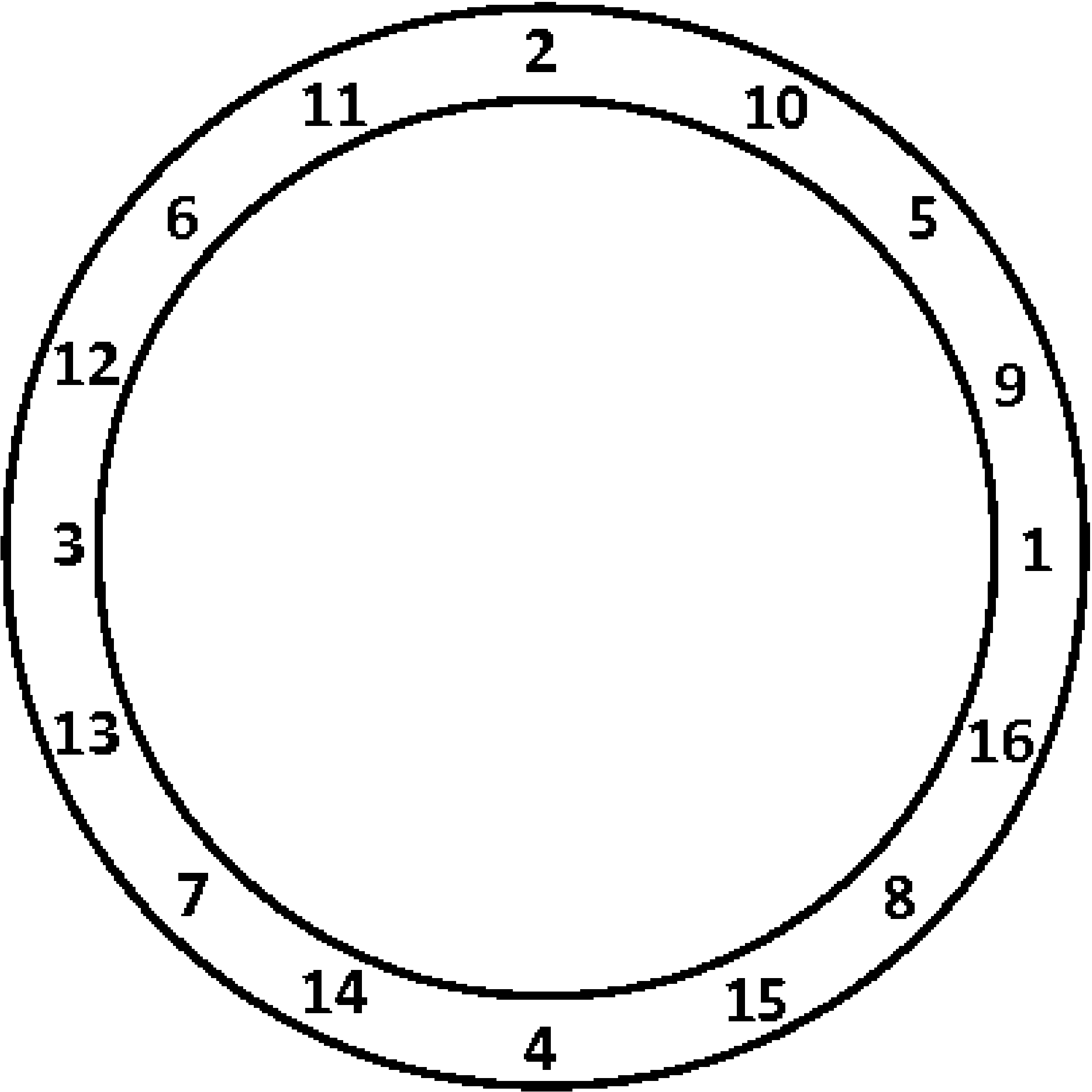

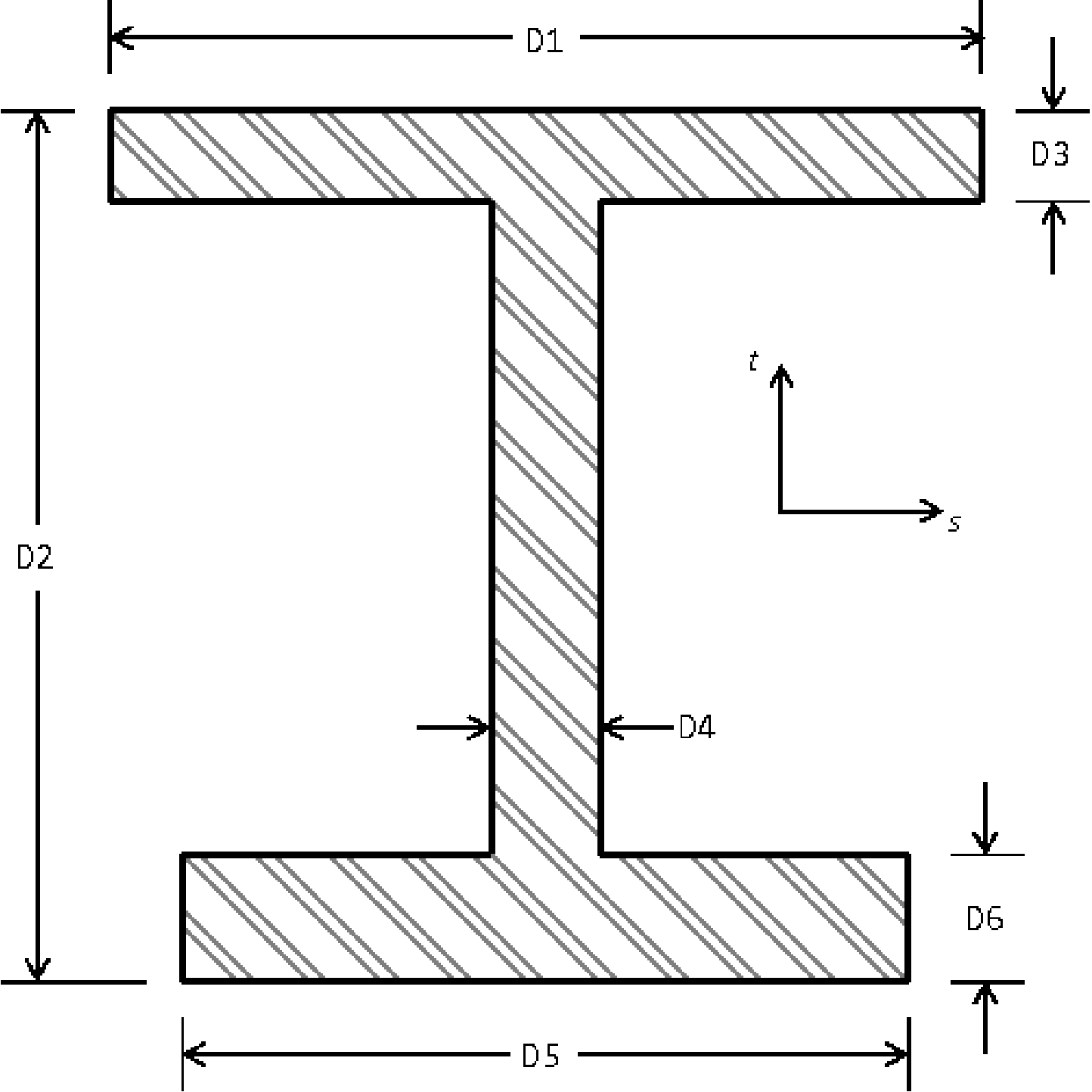

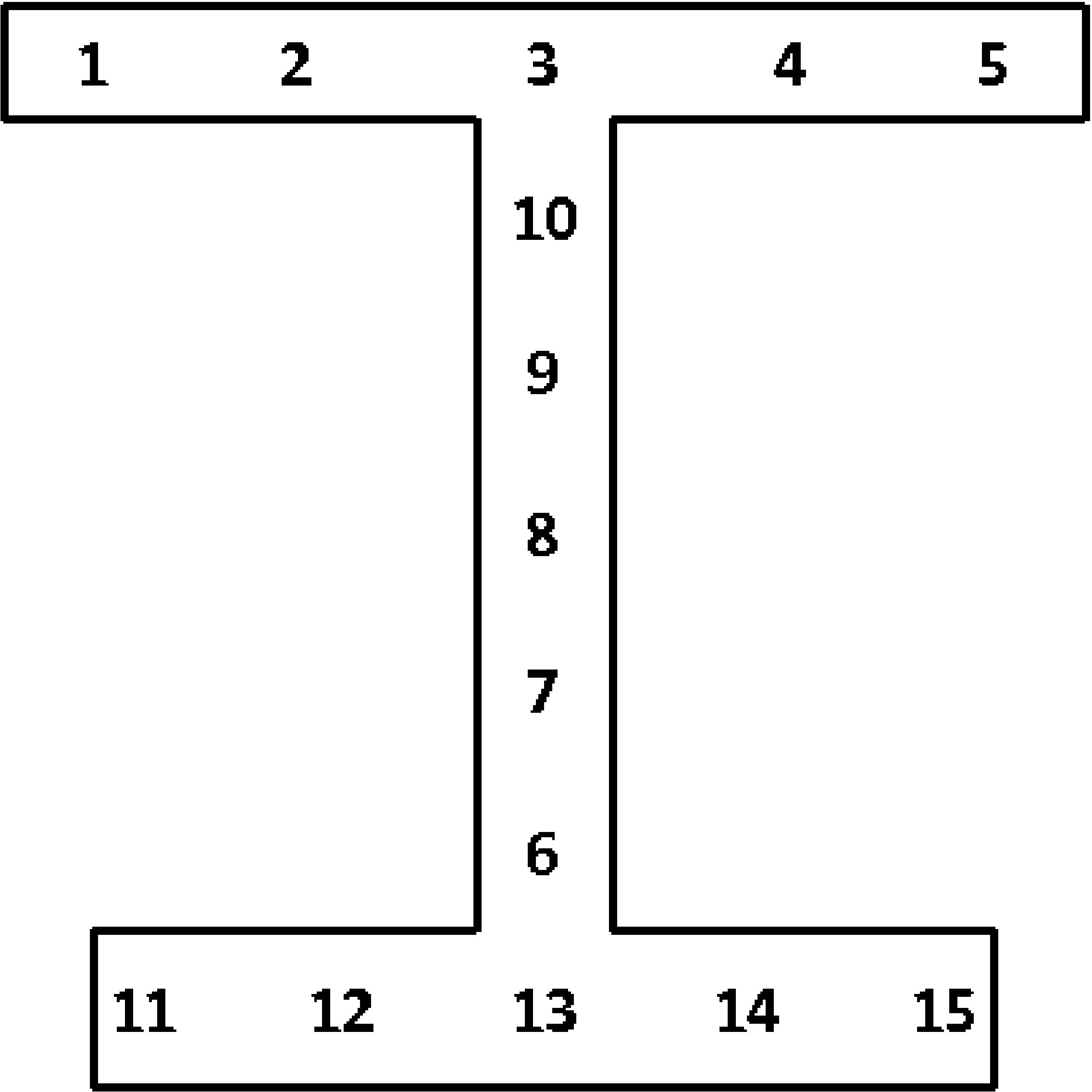

AXIS OFFSET VARIABLE = <string>axis_offset_var