3.2.3. Radiation Transport Equation

For applications involving PMR, both the radiative heat flux and the divergence of the radiative heat flux are needed. The radiative heat flux vector provides the radiative flux to the boundary of the heat conduction region. The flux divergence provides one of the principal volumetric heat sources in the turbulent combustion region for fire applications.

3.2.3.1. Boltzmann Transport Equation

The spatial variation of the radiative intensity corresponding to

a given direction and at a given wavelength within a radiatively

participating material, , is governed by the Boltzmann transport

equation. In general, the Boltzmann equation represents a balance

between absorption, emission, out-scattering, and in-scattering of

radiation at a point. For combustion applications, however, the

steady form of the Boltzmann equation is appropriate since the

transient term only becomes important on nanosecond time scales

which is orders of magnitude shorter than the fastest chemical

reaction [7].

Experimental data shows that the radiative properties for

heavily sooting, fuel-rich hydrocarbon diffusion flames

(% to

% soot by volume) are dominated by

the soot phase and to a lesser extent by the gas phase

(Modest [8], pg. 425).

Since soot emits and absorbs radiation in a relatively constant

spectrum, it is common to ignore wavelength effects when modeling

radiative transport in these environments. Additionally, scattering

from soot particles commonly generated by hydrocarbon flames is

several orders of magnitude smaller that the absorption effect

and may be neglected [7]. With these assumptions

in mind, the appropriate form of the Boltzmann radiative transport

equation for heavily sooting hydrocarbon diffusion flames is

(3.62)

where is the absorption coefficient,

is the intensity

along the direction

, and

is the temperature.

The flux divergence (on the right hand side of (3.33)) may be written as a difference between the radiative emission and mean incident radiation at a point,

(3.63)

where is the scalar flux. The quantity,

, is often

referred to as the mean incident intensity [9].

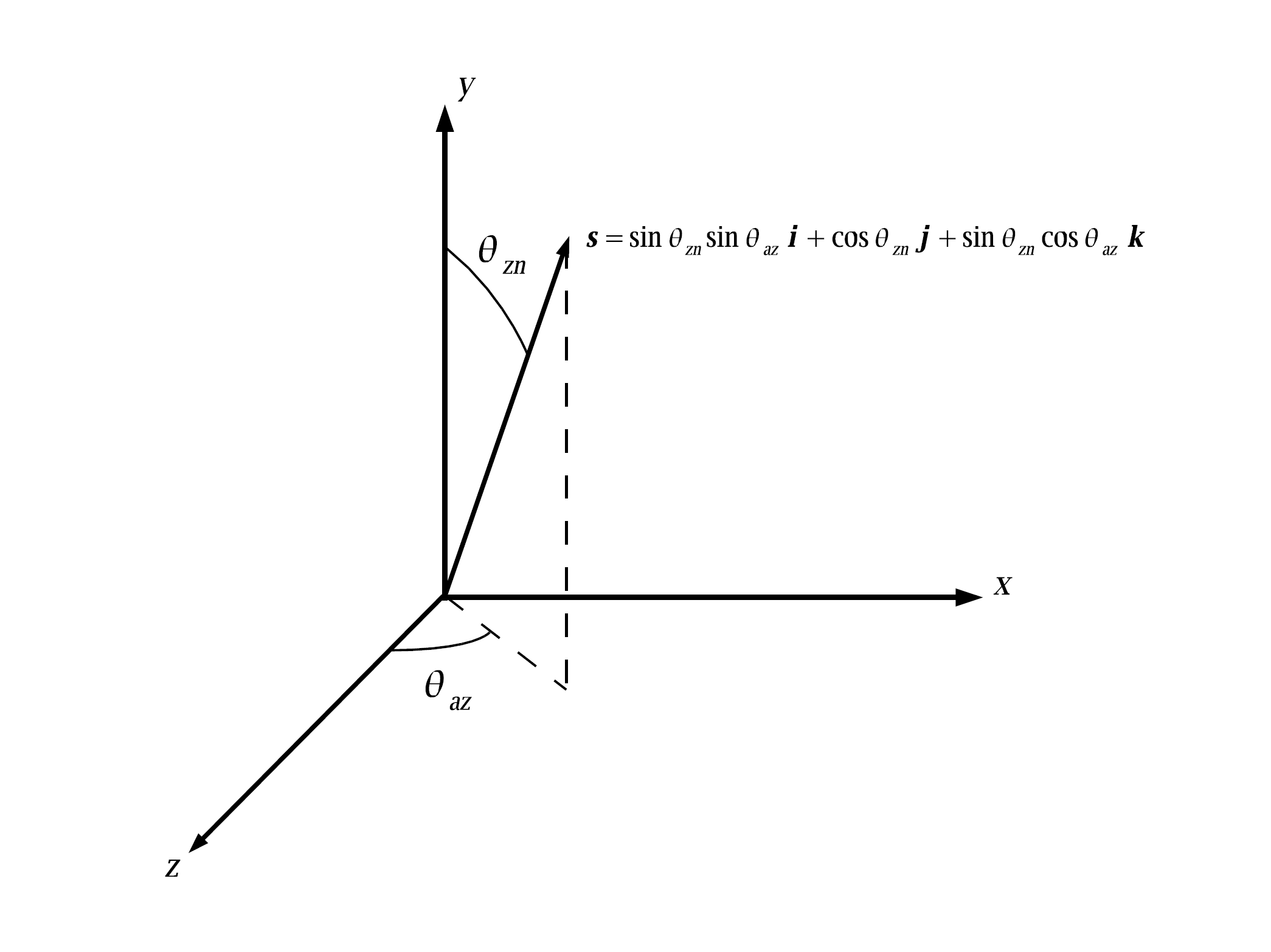

The scalar flux and radiative flux vector represent angular moments of the directional radiative intensity at a point [8],

(3.64)

(3.65)

where and

are the zenith and azimuthal

angles respectively as shown in Ordinate Direction Definition, with

.

Fig. 3.1 Ordinate Direction Definition

3.2.3.2. Radiation Intensity Boundary Condition

The radiation intensity must be defined at all portions

of the boundary along which , where

is the

outward directed

unit normal vector at the surface. The intensity is applied as a

Dirichlet condition which must be determined from the surface

properties and temperature. The diffuse surface assumption

provides reasonable accuracy for many engineering combustion

applications. The intensity leaving a diffuse surface in all

directions is given by

(3.66)

where is the total normal emissivity of the

surface,

is the transmissivity of the surface,

is the

temperature of the boundary,

is the environmental

temperature and

is the incident radiation, or irradiation for

direction

. Recall that the relationship given by Kirchhoff’s

Law that relates emissivity, transmissivity and reflectivity,

, is

(3.67)

where it is implied that .