LEDs promise brighter future, not necessarily greener

By Neal Singer

Solid-state lighting pioneers long have held that replacing the inefficient Edison light bulb with more efficient solid-state light-emitting devices (LEDs) would lower electrical usage worldwide, not only decreasing the need for new power plants but even permit some to be decommissioned.

But in a paper published Aug. 19 in the Journal of Physics D, a band of leading Sandia LED researchers argue for a wider view.

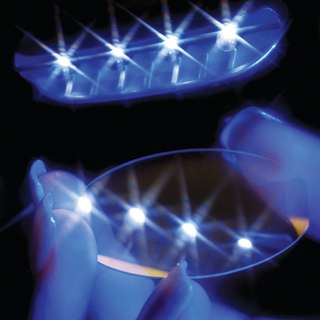

LEDs will change the way we light our world. (Photo by Randy Montoya)

“Presented with the availability of cheaper light, humans may use more of it, as has happened over recent centuries with remarkable consistency following other lighting innovations,” says lead researcher Jeff Tsao (1120).

More light — the ability to work past sunset, indoors or outdoors — has clearly increased personal and societal outputs. Jeff says, “That is, rather than functioning as an instrument of decreased energy use, LEDs may be instead the next step in increasing human productivity and quality of life.”

The assumption that energy production for lighting will decline as the efficiency of lighting increases is contraindicated by data starting with the year 1700 C.E. Those figures show light use has remained a constant fraction of per capita gross domestic product as humanity moved from candle to oil to gas to electrical lighting. Thus the societal response to more efficient light production has been a preference to enjoy more light, rather than saving money and energy by keeping the amount of light produced a constant.

“Over the past three centuries, according to well-accepted studies from a range of sources, the world has spent about 0.72 percent of the world’s per capita gross domestic product on artificial lighting,” says Jeff. “This is so for England in 1700, in the underdeveloped world not on the grid, and in the developed world using the most advanced lighting technologies. There may be little reason to expect a different future response from our species.”

Far from an example of light gluttony, Jeff says, by increasing the amount of lit work space and bright time, individuals would enjoy the desirable outcome of increasing their creativity and the productivity of their society.

On the other hand, societal controls that increased the price of electricity by small, fine-tuned amounts could reduce the amount of energy used, while allowing smaller but still hefty increases in lighting because of the increased efficiencies of LEDs.

To the question of how much light is enough, says Jeff, no one yet has produced a gold standard for light saturation levels.

While artificial illumination is considerably better now than decades ago, the researchers write, “People might well choose higher illuminances than they do today, particularly to help mitigate losses in visual acuity in an aging world population.” More easily available light also may help reduce seasonal depression brought on by the shorter darker days of winter, and help synchronize biological rhythms, called circadian, that affect human behavior day and night.

As for problems that could occur with too much light — from so-called ‘light pollution’ that bedevils astronomers to biological enzymes that operate better in darkness — Jeff has this to say: “This new generation of solid-state lighting, with our ability to digitally control it much more precisely in time and space, should enable us to preserve dark when we need it.” There is no reason to fear, Tsao says, that advancing capabilities “will keep us perpetually bathed in light.”

Jerry Simmons (1120), another paper author, points out, “More fuel-efficient cars don’t necessarily mean we drive less; we may drive more. It’s a tension between supply and demand. So, improvements in light-efficient technologies may not be enough to affect energy shortages and climate change. Enlightened policy decisions may be necessary to partner with the technologies to have big impacts.”

Other authors of this paper are Randy Creighton and Mike Coltrin (both 1126), and Harry Saunders of Decision Processes Inc., of Danville, Calif.

The work was supported by Sandia’s Solid-State Lighting Science Energy Frontier Research Center, funded by DOE’s Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The paper is available for a month, according to the journal, at