For engineers and scientists at Sandia, the evening of Friday, March 12, marked a proud moment in exceptional service to the nation. Hundreds of miles above the Earth, the Multispectral Thermal Imager satellite reached its 10th anniversary of service as it completed its 55,000th orbit — far exceeding both its intended maximum life and its potential applications in the process.

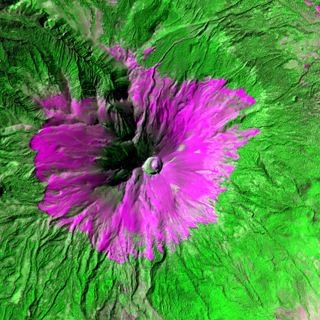

MTI imagery of Popocatépetl volcano in Mexico reveals subsurface hot spots and maps magma channels, while other thermal bands provide information on the effects of escaping gases. The goal is to improve computer simulations needed to model volcanic activity and environmental impacts. The study of volcanoes is important because they represent one of the most active features of landscape generation and can pose a threat to humans and the environment.

NNSA sponsored the MTI satellite project as a trilab effort to develop and evaluate advanced space-based technology for nonproliferation treaty monitoring and other national security and civilian applications. The project was carried out by DOE’s Savannah River National Laboratory and NNSA’s Los Alamos and Sandia laboratories. Sandia served as the lead lab, responsible for systems engineering, integration, testing, launch support, and on-orbit operations.

“This has been an exhilarating program to be a part of,” says Randy Bell, director of the Office of Nuclear Detonation Detection and former MTI program manager. “[The MTI program] achieved many firsts in satellite engineering and remote sensing science. The program relied on a small, experienced, dedicated core team that ensured there was great technical and programmatic communication across all subsystems and science elements.”

Originally only intended for a one- to three-year mission, the MTI satellite was designed to provide highly accurate radiometry with good spatial resolution in 15 spectral bands and to measure ground temperatures from space with accuracies in the realm of one Kelvin.

For a PDF version of this file with more images generated by MTI satalitte data, click the photo at left.

“After reaching the DOE program’s three-year goal, the asset was still functional and providing us with important data but was without a primary sponsor,” says Brian Post (5764), current project lead for the MTI satellite. “By leveraging many small funding sources between existing and new proj- ects, we were able to continue supporting minimized operations for the MTI for a period of time until we could secure new overall sponsorship for the project.”

Overcoming obstacles

After completing the initial nonproliferation mission, the scientists, engineers, and technicians supporting the MTI began to use the satellite in new mission roles, and were obliged to deal with a multitude of unexpected or unplanned issues to keep the system mission capable.

“Having gone well beyond its one-year mission, several anomalies arose over the following years that threatened to end the mission,” Brian says. “The inertial reference unit failed, the onboard calibration capability was lost, the focal plane array was damaged when the sun unexpectedly entered the telescope’s field of view, the MTI’s long-term orbit plane drifted beyond its design limit, and the satellite experienced battery failures and other power and control problems. Each time, the outstanding project team was able to mitigate these issues and keep the satellite operating and functional.”

Through their innovations, the operations team and the system’s original designers at Sandia and Ball Aerospace not only succeeded in nursing the MTI back to life, but they also made design improvements to the MTI that enhanced the system capabilities and imaging capacity.

“The data and research results that have come from the MTI project in the more than 10 years it has operated more than justify the satellite as a worthwhile investment,” Brian says. “I truly believe we are lucky as a nation to have the MTI and to have kept it going as a resource. The value of this asset and technology is shown not just in the original mission we completed, but also in the multitude of other projects and programs that the MTI either initiated or contributed to directly.”

Serving science beyond nonproliferation

NNSA made the MTI system available to other users for government-sponsored research in the national interest after the satellite had completed its initial goals. As it turned out, the 15 spectral bands that the MTI science team had selected to address the program’s nonproliferation mission also provide valuable data to scientists who study a vast array of geophysical and other environmental phenomena, with applications never envisioned by the MTI developers. In addition to numerous defense-related applications, the more than 100 members of the MTI users group have employed the satellite’s imagery for research in such diverse areas as volcanology, glaciology, entomology, climatology, and the study of the moon.

“An important goal for us was to make our data available to the community,” Brian says. “And not just provide that data, but provide it in a format that researchers can understand, use, and manipulate in their work.”

The MTI’s data and imaging capabilities have proven useful to researchers studying the health of glacier ice, as well as the character of the permanent or seasonal ice pack in the Arctic or Antarctic, which can give climate scientists information they need to refine global climate models. The MTI has also provided useful data to researchers who study clouds in an effort to understand their effect on global warming. In addition to the direct scientific contributions of the MTI data, images have also been used as a resource for algorithm and signal processing technique developments.

Continuing to serve into the future

With sponsorship secured for the foreseeable future of the MTI satellite, the project team eagerly looks forward to years of continued work supporting research and development interests. “Based on our latest predictions, the satellite still has many years of life left on orbit prior to re-entry,” Brian says. “We look forward to continuing our work contributing to and enabling our nation’s research and technology development. Particularly with the full lifespan of the satellite in mind, this has been a fantastic government investment and an incredibly successful project.”

The MTI project was the collaborative work of more than 500 Sandians from across 36 centers and more than 100 departments at Sandia, and more than a thousand others across all the program’s participants.

“The outstanding results of the MTI program are the product of a lot of hard work and attention to detail from a lot of people,” says Brian Brock (5735), original project manager for the MTI. “The satellite was designed with such a radiometric accuracy and precision that LANL and the National Institute of Standards and Technology had to develop new standards to calibrate it. When the MTI launched, there simply was nothing like it and it is still a unique asset. It was truly a world-class product from a world-class team.”

“This program clearly demonstrated that it’s the quality of the people that matter most in the quality of the outcome,” Bell says. “Throughout all phases of the program from initial planning, design, development, launch, and operations, there was a careful balance between rigorous engineering to ensure reliability and exploratory science to push the limits of performance.”

“I owe a debt of gratitude to both our incredibly capable project team and also to the original subject matter experts who, although not actively working on the project, never cease to come to our aid when needed,” says Brian Post.

Other participants in the MTI satellite project include the Air Force Research Laboratory, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Ball Aerospace, Santa Barbara Research Center, Hughes Danbury Optical Systems, TRW, more than 40 other commercial and academic institutions in 16 states, and a users group with experimenters representing more than 50 government organizations.