6.6. Guidelines

The present section offers some useful guidelines for various user settings, which can be a useful starting point in setting up an analysis.

6.6.1. Initial Time Step Estimation for Thermal Problems

A method for estimating an appropriate initial time step is outlined below. This procedure is originally due to Levi ([51]) though it has been discussed by several other authors ([52, 53, 54]).

In the following development, it is assumed that a finite element mesh has been

constructed that will adequately model the thermal phenomena of interest (e.g.,

thermal shock problems will require a fine mesh near a boundary while slower

thermal transient will be less demanding on mesh refinement). For a given

spatial discretization, a local characteristic length, , is chosen

based on element size. Typically, this characteristic length is measured normal

to a boundary on which a temperature or heat flux (source) disturbance occurs.

Based on the characteristic length, the local heat transfer coefficient,

,

and the local thermal conductivity,

, a local element Biot number (

) can be computed. Note that for a prescribed temperature, heat

flux or heat source boundary condition, the heat transfer coefficient,

, is

assumed to be large leading to a large Biot number.

In order to bound the thermal gradient that will occur at the boundary in the

first time step, the ratio of the temperature at a distance

(characteristic length) from the boundary to the temperature on the boundary is

selected. Let this ratio be defined by

.

Typical values of

will range from 0.10 to 0.25. With the estimated

values for local Biot number and temperature ratio

, a local Fourier

number (

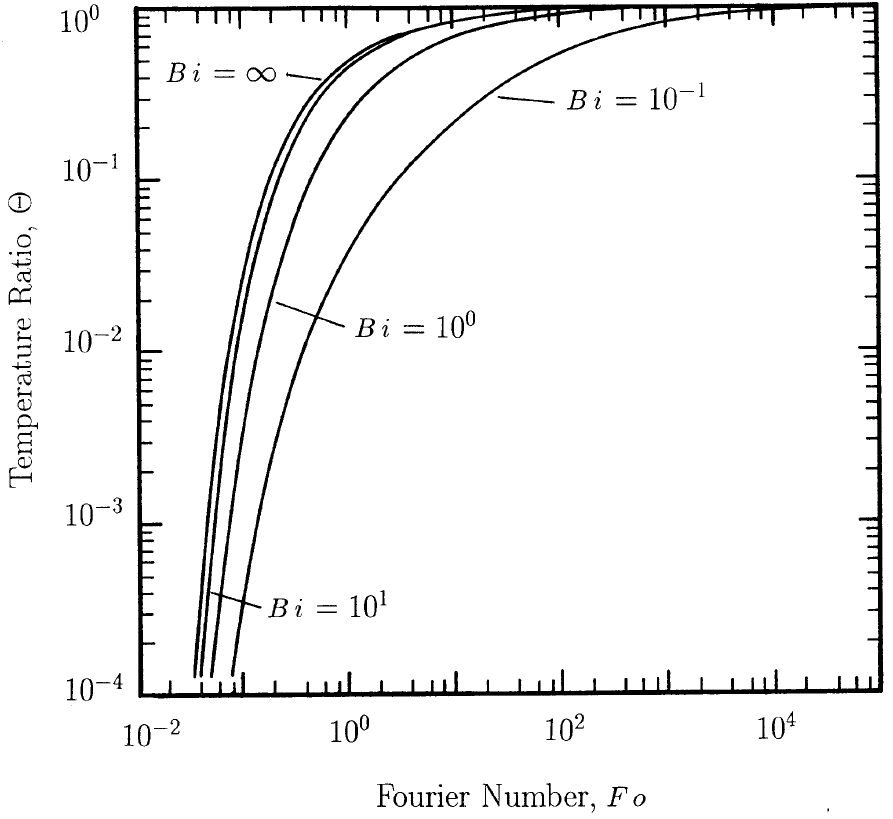

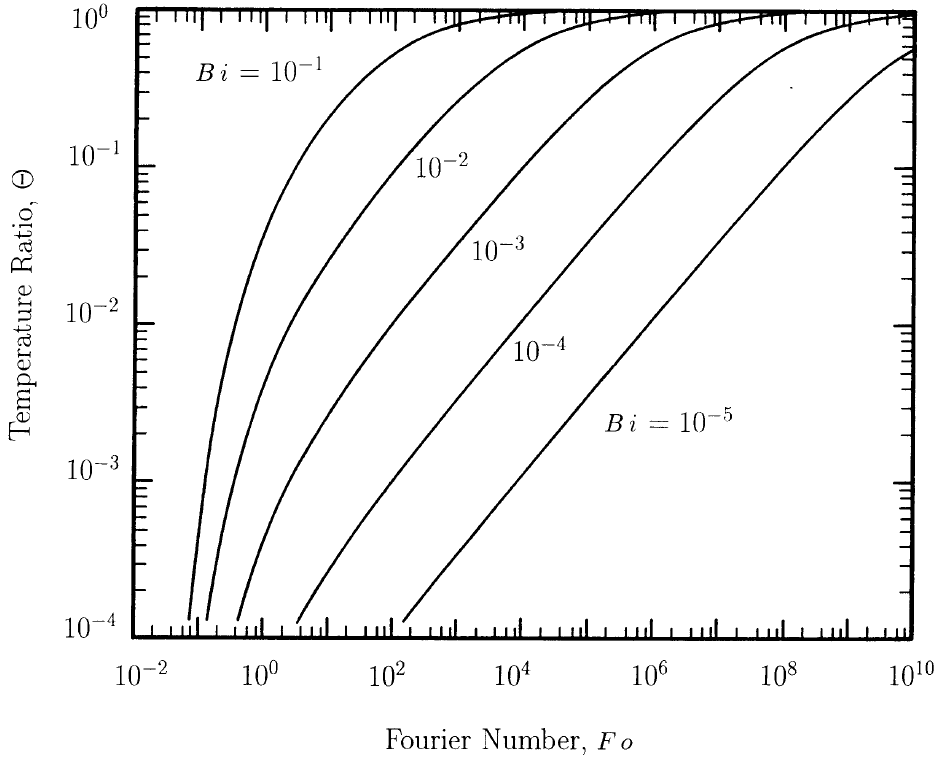

) may be found from the charts in

Fig. 6.1 and Fig. 6.1. These graphs are based on

an analytic solution for one-dimensional conduction with a convective boundary

condition ([55]). A value of the local Fourier number and values

for the characteristic length and thermal diffusivity,

, then allow a

time step to by computed.

Fig. 6.1 Temperature ratio versus Fourier number for various Biot numbers

Fig. 6.2 Temperature ratio versus Fourier number for various Biot numbers

As an example of the procedure outlined above consider the transient problem described in the following example:

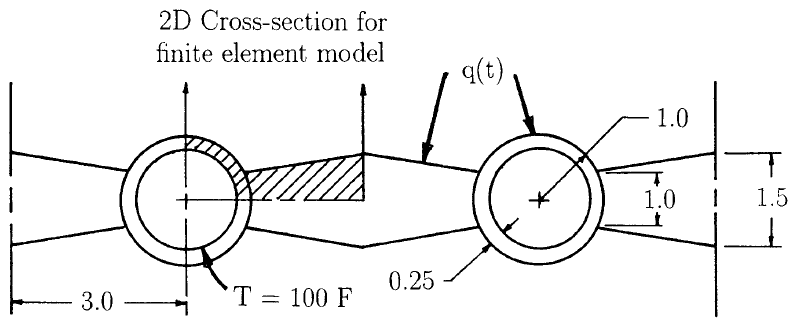

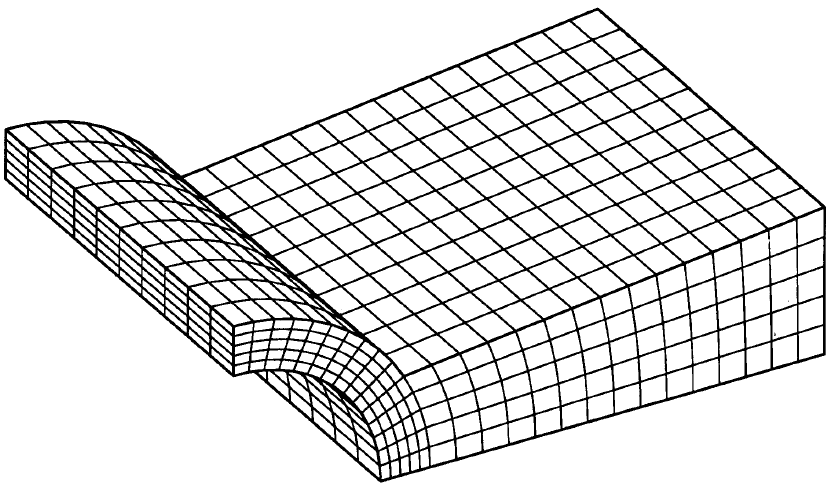

Geometry and mesh of finned radiator problem (Dimensions are in inches)

Consider the transient thermal response of a finned tube radiator, as shown in Finned Radiator. Thermal properties for the radiator are as follows:

The characteristic size is based in the average size of

the elements along the radiator fin, as shown in Finned Radiator,

and is equal to m. The boundary condition is

an applied heat flux, so the Biot number is assumed large (infinite). Using a

temperature ratio of

, then Fig. 6.1 yields a

Fourier number of

. Thus,

The above procedure can also be used to estimate the overall response time for a region. In this case the length scale is a characteristic length for the entire region and the temperature ratio should be order unity. The Fourier number will then produce the approximate time interval required to reach equilibrium.