3.6. Radiation

3.6.1. Surface Radiation

A surface may exchange energy with its surroundings through thermal

radiation. Any incident surface radiation will be either transmitted,

reflected or absorbed. Letting ,

and

represent

the fractions of the incident flux in each category then

and for no transmission

Using the Kirchhoff identity

then the reflectance is

(3.100)

where is the emissivity.

In order to understand the radiative energy balance at a surface one considers the rate at which energy streams away from the surface, the radiosity, defined as

(3.101)

where is the blackbody emissive power and

is the irradiation.

Substituting for the reflectance (3.100) then

(3.102)

The surface flux is the difference between the energy that radiates away

and the incident energy

(3.103)

and substitution for the radiosity we find that

When is derived from an external temperature interaction

this boundary condition is often called far-field radiation, since it usually

models the radiative transfer of energy between a surface and the

external environment. However, the boundary condition is found

to have more general utility when one considers its role in

modeling radiative transfer between two surfaces,

&

,

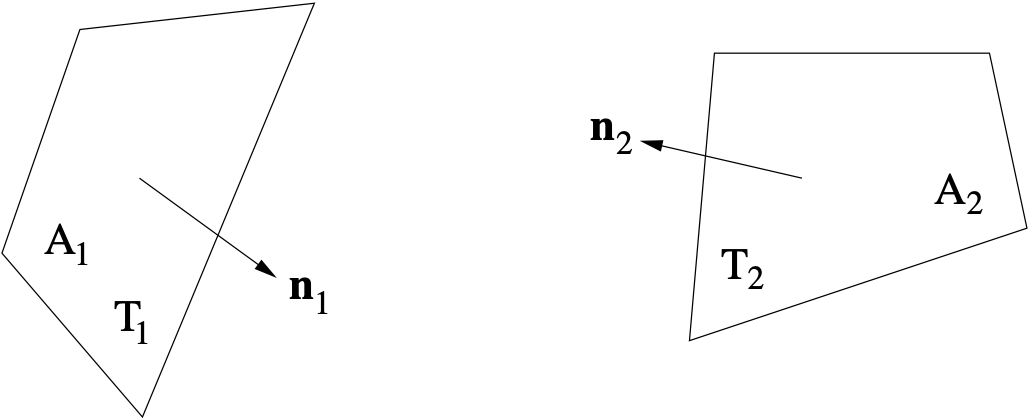

as shown in Fig. 3.3, where

is

analogous to

.

Fig. 3.3 Surface Radiative Exchange

For the case in which the temperature

is known and independent of temperature

then

using the emissive power

the normal flux per unit area across

may be written as

(3.104)

where denotes the Stefan-Boltzmann constant,

is the emissivity of the surface

and

is the form

factor. We remark that

(3.104) is a nonlinear boundary condition, since the

unknown temperature,

is raised to the fourth power and furthermore the

emissivity may be a function of temperature. It is important

to note that the form factor

may differ

from the more familiar view factor

encountered in

enclosure radiation problems. The question often asked is how does one

determine the appropriate value of form factor

.

The form factor can be best described using a

network analogy of radiative transfer between two surfaces as shown below.

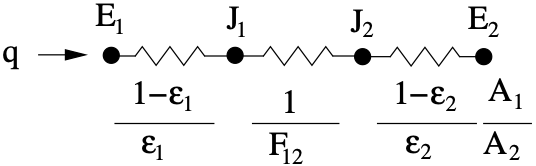

Fig. 3.4 Radiative Transfer Circuit Model

Using the emitted energy and radiosity

the network the heat flux can

be written in terms of a thermal resistance

as

(3.105)

and from the network model

For the third term of

can be neglected and

.

Comparing expressions (3.104) and (3.105) then

so estimation of is not required.

For (black receiving surface) but

and once again the third term of

can

be neglected so that

(3.106)

If both surfaces are black then

from the previous expression (3.106)

we find that

.

During a simulation the surface heat flux is integrated over the

spatial discretization of surface . Here we note that

defining the flux on a per unit area basis enables us to apply the

radiative flux (3.104) consistently with

evaluated

for the entire surface

even when the surface is discretized.

3.6.2. Enclosure Radiation

When energy radiates from one portion of a surface to another, and the intermediate medium is transparent (i.e., it does not absorb any energy), then enclosure radiation may be used to model the heat flux on the surface. Using the net radiation method [18], the normal flux at a particular location on the surface may be written as the difference between the emitted radiative heat flux leaving the surface, and the absorbed incident radiative flux due to the rest of the enclosure, namely

(3.107)

where denotes the absorptivity of the surface, and

represents the surface irradiation. Under the additional assumption

that the emissivity, absorptivity, and reflectivity are independent

of direction and wavelength, we may write

(3.108)

where is the reflectivity.

Without loss of generality, we can regard

the enclosure, , as a

union of

surfaces,

This situation is

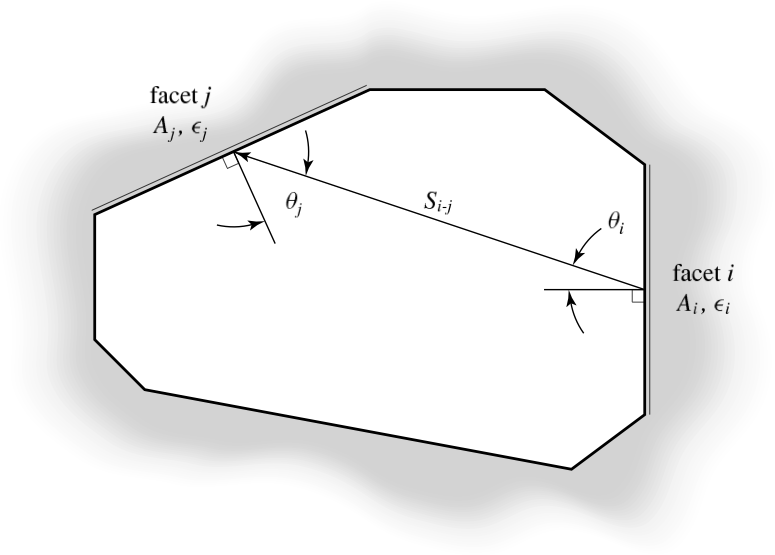

illustrated in Fig. 3.6, where the radiosity for surface in the enclosure is defined to be

(3.109)

where is the area averaged constant temperature on facet

computed via

(3.110)

The surface irradiation for surface is determined by the radiosity

of all the other surfaces in the enclosure through the relation

(3.111)

where denotes the geometric viewfactor of surface

with respect to

surface

. The viewfactor may be considered as the fraction of energy that

leaves surface

and arrives at surface

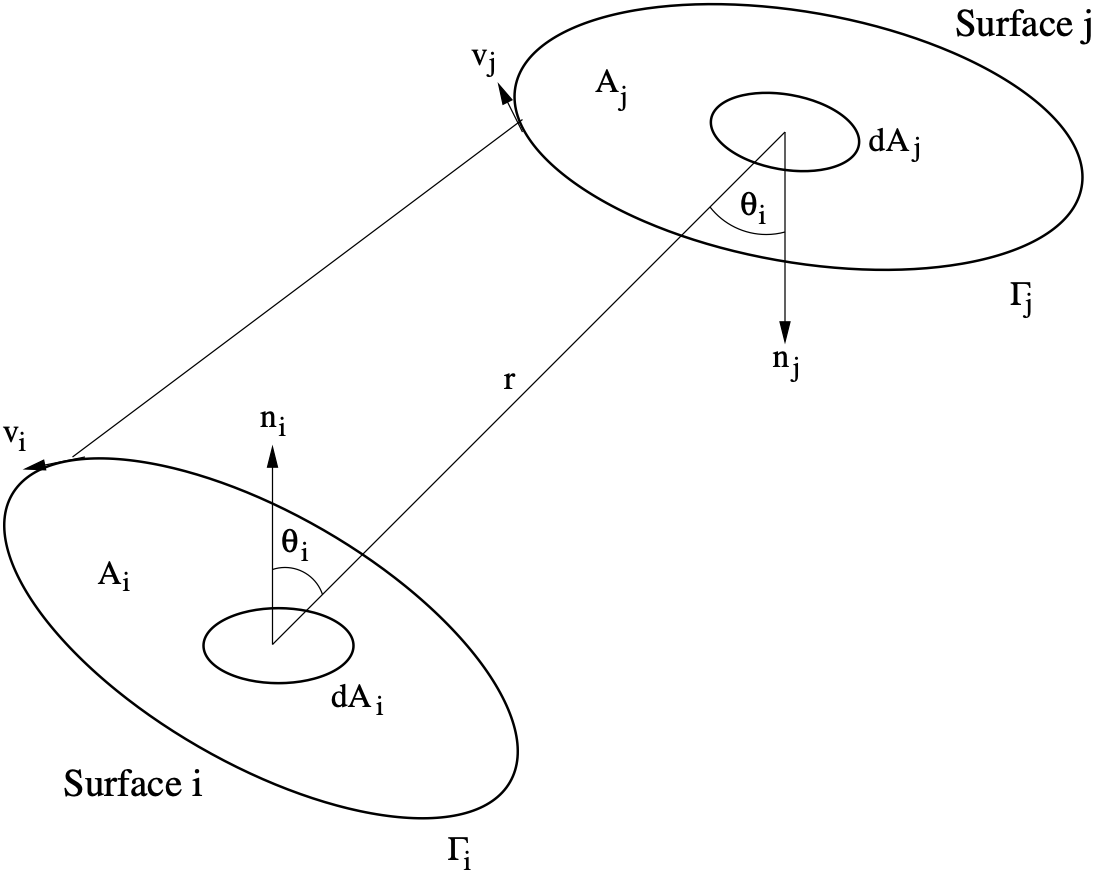

. For a given pair of surfaces shown in Fig. 3.5,

the viewfactor is defined as the following integral

(3.112)

Fig. 3.5 Viewfactor Configuration.

Viewfactors are computed using the Chaparral library [19].

Determination of the viewfactors is a compute intensive endeavor. As such, extraneous calculations

are eliminated based upon the geometry. One example of this would be excluding this calculation for surfaces

which are not visible to each other. Moreover, from a geometric view of

enclosure surfaces, Fig. 3.5, one can conclude that

legitimate interactions between surfaces are those for which and

are opposed. Thus an important feature of the enclosure model is the notion of

inward facing normals. This convention effectively defines the interaction

between the enclosure subfacets.

Note

For closed surfaces (watertight enclosures), for each facet the

row-sum over all surface

facets should equal one, i.e.,

.

Fig. 3.6 Two arbitrary facets radiating energy to one another

in a radiation enclosure. The energy exchanged depends on:

the shape, orientation, distance, area ,

,

temperatures

,

, and radiative properties of the

facets

,

.

Upon substitution of equations (3.111) and (3.108) into (3.109), the radiosity may be written as

(3.113)

Finally, the first term in (3.113) may be moved inside the summation

to yield

(3.114)

where

(3.114) is a system of equations that can be solved for the unknown radiosity at each face.

Finally, we may rewrite (3.107) to express the radiative heat flux on

surface as

(3.115)

where is given by (3.111) and depends on the unknown radiosity.

This heat flux is applied as a boundary condition to the appropriate energy equations, thereby fully coupling

the enclosure radiation problem with the volume energy equations.

Instead of solving the monolithic equation system by forming the jacobian for the combined coupled system of equation systems, a segregated approach is used. At each nonlinear iteration, the radiosity equation is solved separately with the right hand side computed from the average facet temperature (3.110) using the current nonlinear temperature solution. Subsequently, the irradiation is computed from the radiosity in order to compute the heat flux contribution given by (3.115). A Newton step is then performed where the jacobian contribution of the radiative flux is computed as

(3.116)

where is the

nonlinear temperature residual,

the test function and where

(3.117)

Here, the facet temperature given by (3.110) has been relabeled to

to avoid confusion with the nodal finite element temperature solution. The sensitivity of the radiative

heat flux with respect to the facet temperature is approximated as

(3.118)

while the sensitivity of the facet temperature with respect to the nodal temperature dof is

(3.119)

where is the area of a facet. In terms of the element contribution, this can be compactly written

as

(3.120)

Note

The average facet temperature is . For computing the cube

, experience shows

projecting the raised power i.e.,

leads

to less spurious oscillations.

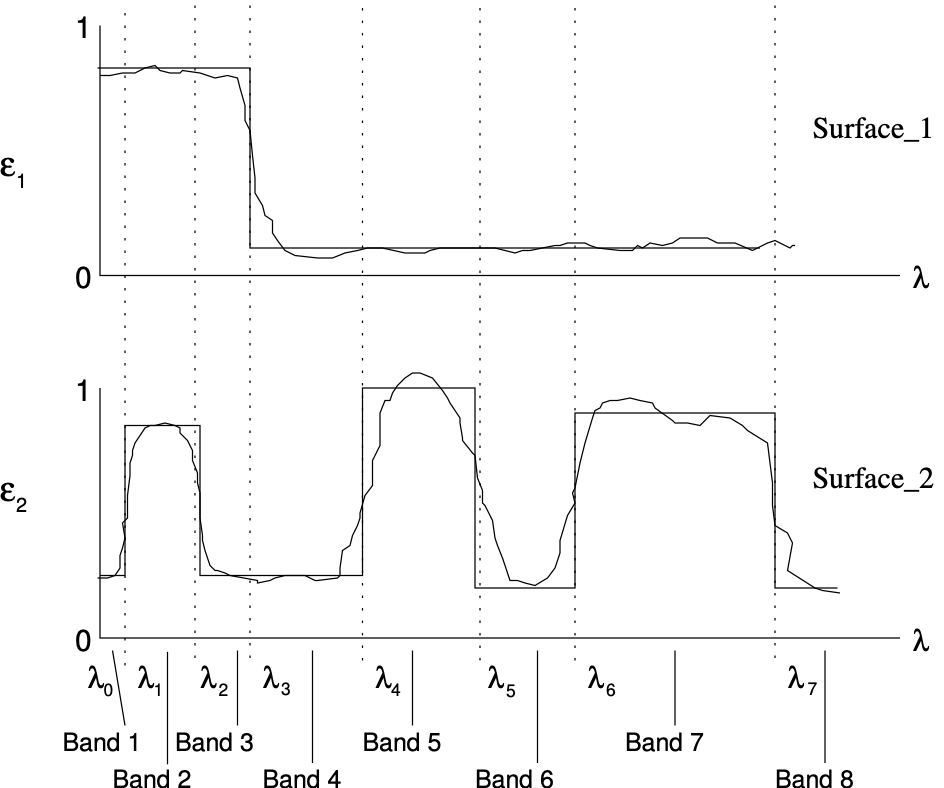

3.6.3. Banded Wavelength Enclosure Radiation

The enclosure radiation model previously presented considers a net response over all wavelengths assuming that all surfaces behave as grey bodies. Here the surface response with regard to different wavelengths is implicitly included in the model by using temperature dependent emissivities and allowing the surfaces to emit as grey bodies. In this case the surface flux previously mentioned (3.107) can be alternatively expressed as

(3.121)

In many applications engineering materials respond differently to different

portions of the thermal energy spectrum. Thus modeling the thermal radiation

response of these materials using the entire blackbody spectrum results in poor

characterization of the enclosure response. For this purpose more specialized

approaches for radiation modeling of wavelength dependent surfaces have been

developed using continuous representations of emissivity as a function of

wavelength and temperature while integrating over the wavelength spectrum. For

numerical modeling the simplest approach involves discretization of the

wavelength spectrum into a few representative bands and integrating over

each of the

bands. Using this approach the methods previously described

follow directly except that the emissivity and emissive power now have

independent representations in a wavelength band, each of which contributes some

surface flux

thus

(3.122)

Recalling that flux can also be expressed in terms of radiosity then similarly the radiosities are obtained by solving a system of equations

(3.123)

where is the incremental radiosity and

is the blackbody fraction for band

.

Finally we note that given a fixed facet temperature field this solution can be carried out

independently for each wavelength band and the radiosities

can

be accumulated to obtain the net facet radiosity

and net flux

.

Thus the banded wavelength model very much resembles the more simplified enclosure radiation model.

From a simulation point of view, the major difference being that the modeler must supply information describing

the band discretization in addition to emissivity models for each band.

Construction of the banded wavelength model begins by first prescribing the

emissivity variation for each surface of the enclosure as a function of

wavelength . The overall band discretization is then obtained by

collective consideration of the wavelengths at which the emissivity changes on

any of the given surfaces. Thus the number of bands for the enclosure will

likely be more than those for any single surface and is demonstrated in

Fig. 3.7 below.

Note

Each modeled band must have an emissivity model supplied for each surface, even when its emissivity is not changing.

Fig. 3.7 Emissivity bands for two-surface problem.